Friday Night Legends: A.L. Brown’s Haskel Stanback

Published 12:00 am Friday, August 21, 2015

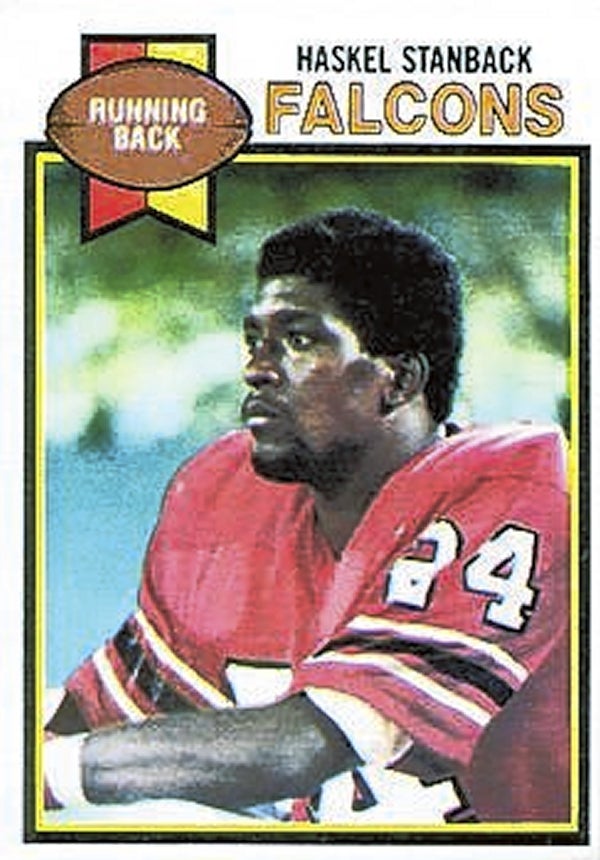

- Haskel Stanback's football card from 1979.

By Mike London

mike.london@salisburypost.com

KANNAPOLIS — It was opening night in 1967, glory days for the old South Piedmont Conference, and Boyden High quarterback Bill Leonard broke a dazzling scoring run to send the home fans into a frenzy.

But the cheering subsided abruptly. Boyden’s lead against visiting A.L. Brown lasted only 20 seconds because a fleet sophomore halfback, making his debut, sprinted 60 yards for the first of his many touchdowns for the Wonders.

His name was Haskel Stanback.

Stanback is 63 now but still looks legendary. Tall and strong, with the posture of a Marine drill sergeant.

His athletic endeavors are limited to golf now, but in his day, the running back was a difference-maker for A.L. Brown (21 touchdowns as a senior), the University of Tennessee (SEC rushing leader in 1972) and the Atlanta Falcons (8th on the franchise’s all-time rushing list).

“I was far from the most talented guy to come out of my neighborhood, but a lot of great players never finished high school,” Stanback said. “I was lucky. I got to compete against the best.”

Stanback lives in Locust Grove, Ga., but he visited Kannapolis recently to hug his mother, Mary, who toiled 34 years in the textile mills, and for a reunion with C.A. Suther, who befriended Stanback when he was a teen.

Suther, 84, provided rides home from practice along with the occasional meal for Stanback, who was raised by his single mother in the Bethel section of Kannapolis.

Stanback thinks so much of Suther that he once handed him one of his Tennessee tear-away jerseys after a game.

“Thank you for looking after this man,” Stanback said to former Catawba assistant basketball coach Bill Haggerty, who drove Suther to his reunion with Stanback at Kannapolis’ China Buffet.

It started for Stanback with backyard football. His uncles taught him the game.

As an eighth-grader, Stanback thought he had made the team at Carver, Kannapolis’ school for black students before integration.

“But they told me they couldn’t give an eighth-grader a uniform,” Stanback said. “That was a disappointment.”

As a ninth-grader, he shined for Carver’s Blue Eagles.

As a sophomore, he arrived at A.L. Brown for the 1967-68 school year, and his impact was instant.

As special as he was, Stanback’s high school teams were only good, not great. The Wonders were 18-10-2 overall in his three years and 13-9-2 in the SPC.

Ask Stanback about Concord, and he winces. The Wonders were 0-3 against the Spiders in his era.

“Carver vs. Logan (Concord’s black school) was just as intense as Concord against A.L. Brown,” Stanback said. “People forget that sometimes.”

His fondest Wonder memories are the battles with Lexington. When Lexington won the 1967 Western North Carolina High School Activities championship, it lost only one game — to Stanback and the Wonders.

Lexington was ranked No. 1 in the state and eager for payback in 1968, but the Wonders managed a 14-all tie, as Stanback’s uncles sparred verbally with Lexington supporters in the bleachers.

Besides having serious size and speed, Stanback was a good student and a recruiting target for just about everybody, including the ACC and SEC, conferences that had finally started pursuing talented black athletes.

“My first recruiting trip was to Catawba,” Stanback said with a smile. “C.A. took me up there, and I met Ike Hill (Catawba’s first black player). I liked Catawba, but I was being recruited by schools like Ohio State, Georgia Tech and Tennessee. The first steak I ever ate was when Ohio State wanted me badly and (coach) Woody Hayes took me out to eat at the Holiday Inn in Salisbury.”

Stanback’s dream, believe it or not, was to be a defensive back, specifically to be a defensive back for Ohio State, where his hero Jack Tatum played. Tatum was the best defensive back in college football.

But the recruiting visit to Ohio State proved disastrous.

“It was my first plane flight, and it was 60 degrees when I flew out of Charlotte,” Stanback said. “I get to Ohio State, it’s freezing and there’s snow everywhere. I didn’t even take a coat. Jack Tatum let me borrow his leather one.”

Stanback’s recruiting trip to Georgia Tech was warmer, but Stanback noticed a serious shortage of females. That was a deal-breaker.

“They told me to pick out a few girls and they’d recruit them too,” Stanback said with a laugh.

Tennessee landed him because of the relentless efforts of Tennessee boosters in Kannapolis and Concord and because he liked Tennessee head coach Bill Battle.

The Vols were 28-8 in Stanback’s three seasons, were ranked twice in the top 10 in the final AP poll and won two bowl games, but it wasn’t enough to satisfy the fan base.

“That year we were 8-4, someone sent a moving van to Coach’s house,” Stanback said. “You’ve got to beat Alabama and Georgia or you’re in trouble in Knoxville.”

As a junior, Stanback paced the SEC with 890 rushing yards and 13 rushing TDs. He led a memorable victory against Penn State in the Vols’ first-ever night game.

But he broke his wrist twice at Tennessee, including his senior year. That damaged his draft stock.

The Cincinnati Bengals drafted Stanback in the fifth round. He put up numbers in exhibition games with the veterans on strike, but when they returned, he was cut. He landed on his feet with the Falcons.

Stanback’s career in Atlanta wasn’t long (1974-79), but he rushed 728 times for 2,662 yards and scored 26 touchdowns.

He played a role in the first playoff game in Atlanta history, a 14-13 wild-card victory on Christmas Eve, 1978, against the Philadelphia Eagles. A week later, the Falcons went to Dallas to take on the Cowboys. Stanback lists that game as his most disappointing in the NFL, even though he gained 62 yards on nine carries.

“One of our linebackers, Robert Pennywell, knocked out (Dallas QB) Roger Staubach,” Stanback said. “I can still see Staubach’s head bouncing off the turf and we had a lead going to the fourth quarter. But Danny White led a Dallas comeback.”

The Cowboys won, 27-20.

Stanback was out of football at 27 years old. Fortunately, he was armed with a degree from Tennessee in an unusual major — Transportation and Logistics.

“That led to a good job opportunity with Norfolk Southern railroad,” Stanback said. “I made a whole lot more money with the railroad than I ever did in football.”

He was with Norfolk Southern more than 30 years, rising to superintendent of the company’s Virginia Division before retiring a few years ago.

He’s thankful for his good health and knows it may have been a blessing in disguise that his career didn’t last longer.

“I had a physical the other day and the doctor told me I was doing OK,” Stanback said. “I’ve got a lot of miles on me, but I hope I’ve got about 50,000 left.”

He has two daughters, but no sons-in-law.

“Maybe I need to lighten up,” Stanback said with a laugh.

He talks to young athletes if they’ll listen, but he worries that work ethics aren’t what they were in his day.

“Seems to me like a lot of them are saving themselves for the Big Dance, but they don’t want to do the work it takes to get there,” he said.

Before he left the restaurant, Stanback and his mother embraced Suther and Stanback signed one of his 1978 Topps bubblegum cards for Suther.

“Those were special days we had, weren’t they?” Suther said.

“They still are special,” Stanback said. “They always will be.”