‘The Lego Movie’ has religion

Published 12:00 am Sunday, February 16, 2014

“The Lego Movie,’’ well-reviewed and making money by the brickyard, builds its story upon religious and moral themes. They don’t all snap together securely, but that’s in keeping with the rest of the film.

Right off the bat: It’s as good as the reviews say. The story takes elements from “The Matrix,” “Harry Potter,” “Kung Fu Panda,” “Lord of the Rings,” the good “Star Wars” movies, “Toy Story” and other recent cultural touchstones and blends them into plot slurry. Which is not all that surprising for a modern kids’ movie.

But references to Aristophanes? Ibsen? Orwell? To an architect who died more than 2,000 years ago? I guarantee you did not see that coming.

You’ve likely read a summary of the story: An utterly unremarkable construction worker figure in a Lego city literally falls into a tale where he discovers the “Piece of Resistance,” a plastic doodad that is the only way to stop a dastardly villain (modeled on “Big Brother”) from destroying the world. Our hero, who has never ever deviated from the “official instructions,” has to discover what it means to be “the Special” and lead the battle.

In his quest, he gains allies: A warrior-woman named Wyldstyle; her boyfriend, Batman (yes, that Batman); a half-unicorn/half kitty mash-up named, duh, UniKitty; and others, including a wizard named Vitruvius.

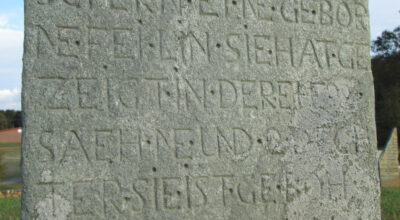

Marcus Vitruvius Pollio was an engineer and architect who wrote a 10-volume encyclopedia on architecture in the first century B.C. His work was so influential that Leonardo da Vinci used it 500 years later to help design his famous drawing of a man inside a circle, the Vitruvian Man.

This Vitruvius is one of the film’s “master builders,” figures able to effortlessly construct anything out of the Lego materials.”Master builder” may be a nod to Ibsen’s play “Master Builder,” about an architect who dies when he falls from one of his buildings. (Yeah, that’s dark.)

Go deeper? The hero of the tale, the anonymous construction guy, is named Emmet, or “truth” in Hebrew. I asked Lego director Philip Lord if this was coincidence.

No, he replied in a Tweet: “ ‘truth’ was Greg Silverman’s idea at WB and we embraced it.” (Silverman is president for creative development and worldwide production for Warner Bros. Pictures.)

Our plucky band ends up at one point in Cloud Cuckoo Land, a chaotic place where there are no rules. That’s an unambiguous nod to Aristophanes’ satirical play “The Birds,” written about 2,400 years ago, which included a chaotic realm called Cloud Cuckoo Land.

Where are the religious and moral references? There are references to the Man Upstairs, the one really in charge of their world. So there’s your Lego God.

There’s a prophecy, by Vitruvius, about that doodad called the “Piece of Resistance” (think Holy Grail or Ark of the Covenant ) and “the Special” (the Only One who can use the Piece to save the world). Which is something like any religious prophesy about a savior.

Emmet also sacrifices himself for his friends, plunges through a tunnel into the Light, learns an unforeseeable truth about his world and is resurrected to return to the quest. That has echoes of Jesus and Guru Nanak, the father of Sikhism.

The whole film turns on finding a balance between conformity and creativity. Vitruvius tells Emmet: “All you need to be special is to believe.”

This is a theme that plays out today in many houses of worship. In fact, the broad popularity of Pope Francis is exactly about the way he is redefining the balance of conformity versus creativity for the Roman Catholic Church.

(And let’s deal with the canard you might have heard: There’s nothing anti-capitalist about the movie. True, the film is opposed to an externally imposed rigidity of thought. And it’s against some of the degrading vulgarities of modern culture. But it’s emphatically “pro-entrepreneurship,’’ which is as pro-business as you can get.

But then there’s a plot twist at the end that I dare not reveal.

It changes our perspective of most of the film. Some of what had been annoying randomness suddenly makes total sense. It also takes what seemed like a tale about imaginary beings and turns it into a story with a message that is both more specific and more universal.

We realize, with perhaps a shock of recognition, that the tension between creativity and necessary rules is hardly limited to the Lego universe. And we get a lesson about how that strain might be resolved.

There one more possible nod to faith: Like Frodo in “The Lord of the Rings,’’ Emmet’s heroic quest would fail except for an act of grace. In this case extended by, ahem, the Man Upstairs.

Are we supposed to understand any of it as real? As Vitruvius tells Emmet: “The prophesy is made up, but it’s also true.”