Streetcars led to development of key Salisbury neighborhoods

Published 12:00 am Saturday, May 17, 2014

SALISBURY — Streetcars played a crucial part in the development of city neighborhoods across North Carolina — and Salisbury was no exception.

The early history of the Fulton Heights, North Main Street and Chestnut Hill neighborhoods is closely entwined with the streetcar line that ran for 33 years between Mitchell Avenue in Fulton Heights and Spencer.

Walter Turner, historian for the N.C. Transportation Museum in Spencer, notes how vital and important the streetcar neighborhoods of the early 20th century became to N.C. cities.

Fulton Heights, in particular, closely mirrored what was happening elsewhere. Streetcar neighborhoods in Charlotte included, for example, Dilworth, Myers Park and Elizabeth. Greensboro saw the development of Irving Park; Raleigh: Glenbury Park and Bloomsbury Park; and Durham: Trinity Park and Lakewood.

And those are only a few examples. Streetcars were vital in providing transportation between Wilmington and Wrightsville Beach, and they served as the link between the Southern Pines train station and the golfing mecca of Pinehurst, six miles away.

“They were away from downtown, sort of in the country,” Turner said of the early streetcar neighborhoods. “Now they’re considered downtown.”

Turner spoke Tuesday night to the Rowan History Club at the Rowan Museum. He has written a research paper on streetcar systems in North Carolina, while also developing a Power Point presentation.

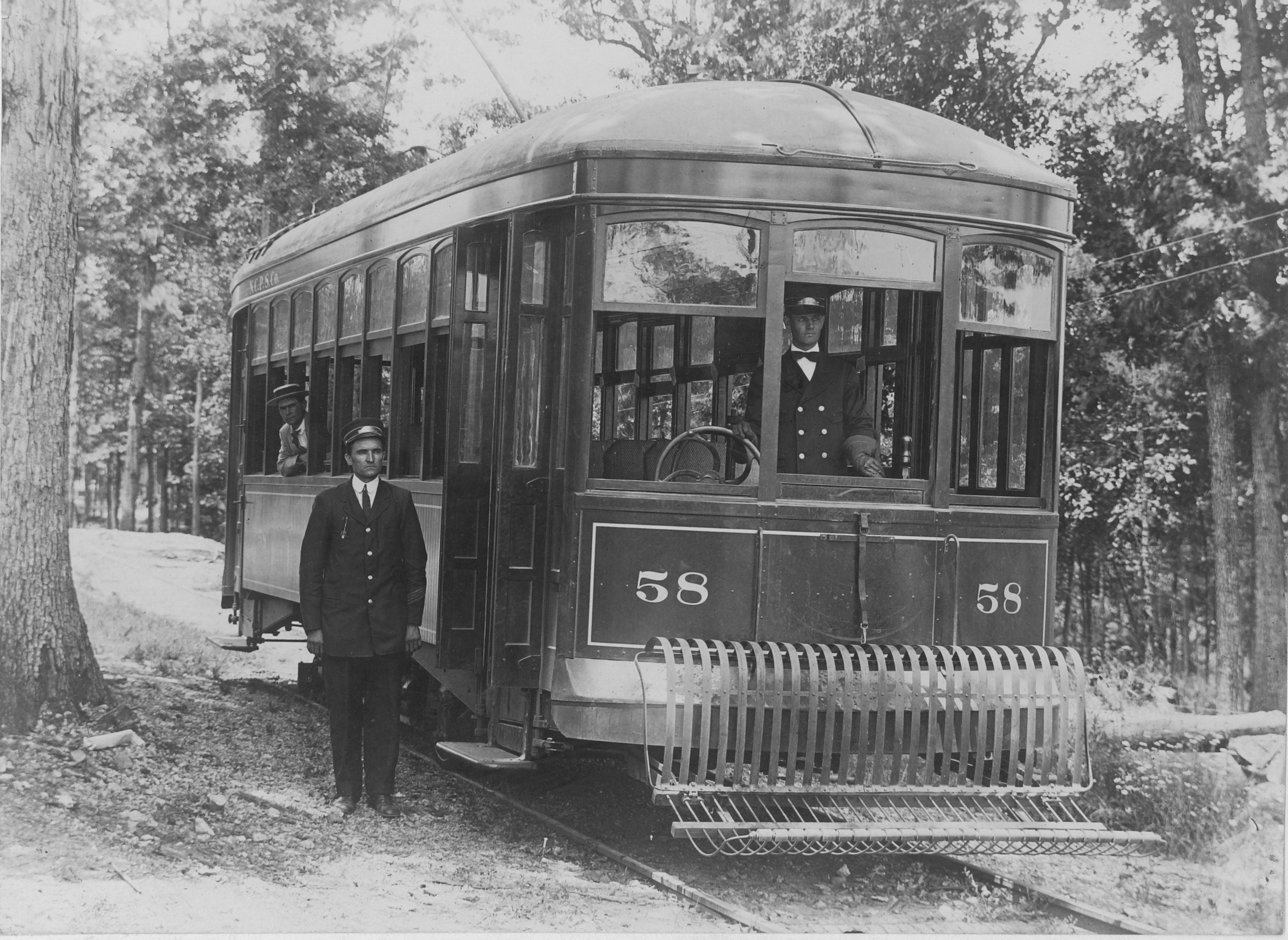

Turner shared many photographs and touched on the importance of streetcars in the expansion of cities such as Charlotte, Raleigh, Asheville, Durham, Greensboro, Wilmington, Pinehurst and Salisbury.

The Salisbury-Spencer Streetcar System operated from 1905 to 1938, originating with the Salisbury Gas and Light Co. before being taken over by Duke Power.

Private-line buses replaced the streetcars in Salisbury and most other cities before they eventually became part of public transportation systems.

The streetcars of the early 20th century were marked by their cheap fares — usually 5 cents per ride — their incompatibility with automobiles and horses and how they often were used as tools to introduce potential home buyers to new housing developments.

Many times, parks and amusements were located at the end of the line. Again, this was the case for Fulton Heights and an amusement park at the end of Mitchell Avenue.

Developers sometimes even built roller coasters as enticements for families to visit the new housing communities.

Asheville had the first electric streetcar system in the state. Winston-Salem was second.

Before electrification, cities had smaller trolleys pulled by mules or horses.

Edward Dilworth Latta took over Charlotte’s horse-drawn trolleys and electrified the system, leading to Charlotte’s first street-car neighborhood in 1891: The new Dilworth neighborhood featured Latta Park.

Fulton Heights’ development took off at least a decade later.

Turner pointed to evidence from photographs of how people relied heavily on streetcars to get them to work or take them to shopping, amusements, ballgames and political rallies.

Many workers going, for example, to Spencer Shops (today’s transportation museum) relied on the trolleys.

Charlotte had a major U.S. Army base during World War I, and streetcars were depended on heavily to transport troops between the train station and base.

Wilmington first had a steam locomotive taking passengers to Wrightsville Beach. In the 1890s that system was consolidated with an electric streetcar company, and trips to the Lumina in Wrightsville Beach became a popular pastime.

In Charlotte, Latta sold the streetcar system to James B. Duke in 1910, and Duke built a park, pavilion and amusements as part of a new Lakewood Park neighborhood.

Turner said everybody could ride the streetcars, though undoubtedly some segregation evolved among the passengers. They routinely could carry 60 to 70 passengers.

As part of his presentation, Turner showed the car barn on North Main Street that once housed and serviced the streetcars.

“Our problem is we have very few streetcar buildings that have survived,” Turner said.

One reason streetcar fares remained so cheap throughout the state was that most systems were owned by utility companies, and they were regulated by the State Utilities Commission. The inability to raise fares might have contributed in part to the street car’s demise, Turner said.

The Salisbury-Spencer Streetcar System made its last run on the night of Sept. 6, 1938.

People made it a party. In reporting on the last trip from Mitchell Avenue to the car barn on North Main Street, the Salisbury Evening Post described the farewell as “a spontaneous celebration from the public that was akin to a circus parade.”

Veteran motorman L.P. Childers, who guided streetcars for 27 years in Concord and Salisbury, was at the controls of the trolley that evening.

“Firecrackers popped, crowds milled about the car — No. 51 — and standing room was almost at a premium as the last trolley started its final run from Mitchell Avenue at 8:07 1/2 o’clock,” the Post reported.

“… No fares were collected and many people — some of them admittedly taking their first as well as last ride on the trolleys here — crowded aboard.”

At the Square, several officials boarded the last car. After it arrived at the car barn, souvenir hunters went into action, stripping the streetcar of placards, light bulbs, parts of the control box, glass in the headlights “and other movable parts,” the newspaper stated.

Childers also was signing autographs.

The mayors of Salisbury and Spencer made a few remarks before turning off the switches of the generator, which furnished power to the streetcar lines. It ended an era.

“The mayors expressed the hope,” the Post said, “that the new bus service would be of even greater usefulness, and since the lines have been extended to include East Spencer, bespoke of closer cooperation between the three municipalities.”

Turner presided over a lively discussion with the History Club audience after his talk. Al Dunn, a Fulton Heights resident, said the streetcar rails are still under the planted median on Mitchell Avenue.

When Piedmont Natural Gas was digging in the median 15 years ago, the rails were evident in the 400 block and portions of the 100 block, Dunn reported.

Julius Waggoner said he rode a Salisbury streetcar once from Thomas Street to Maupin Avenue.

Terry Holt, who presided over the History Club meeting, said its interesting that today’s tourism efforts often use buses made to look like trolleys, as in Salisbury.

“There’s still that fascination,” Holt said.

Contact Mark Wineka at 704-797-4263. Some information and photographs on streetcars is included in the recently published book “Salisbury,” by Larry K. Neal Jr., available at local bookstores.