‘Harriet the Spy’ — it’s all about being a writer

Published 12:00 am Wednesday, June 18, 2014

SALISBURY — It turns out “Harriet the Spy” is not just a simple children’s book about a nosy girl. It’s a book about growing up, learning to be a writer and getting over a loss.

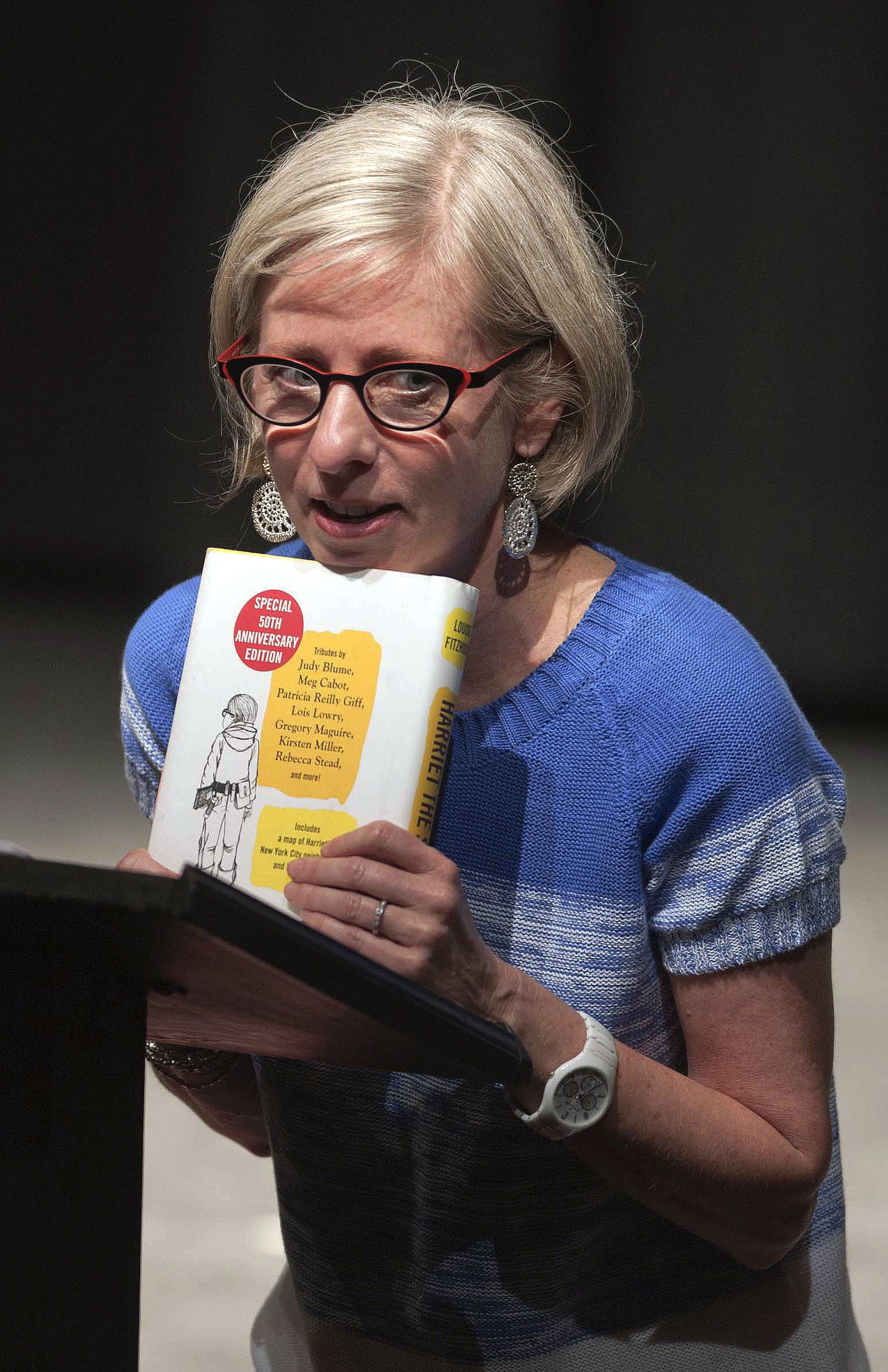

Jennifer Hubbard, who agreed to steer the 2014 Summer Reading Challenge, talked about the book that many writers say inspired them to follow their desires.

“All writers are spies,” Hubbard said. She read the book at age 9 and promptly got a notebook (just like Harriet) and decided she’d spy just like Harriet did.

“For a reader who prefers realistic characters, this book was a godsend. I read ‘Nancy Drew’ but she was kind of perfect, with the perfect car and the perfect boyfriend. Harriet is a lonely, crotchety little girl with a mean streak.

“I found that really refreshing.”

Hubbard talked about Harriet’s creator, Louise Fitzhugh. Fitzhugh was a Southerner who eventually moved to New York to be an artist and a writer. She did all the illustrations in the classic version of the book.

“I love her illustrations, they’re sort of dark and primitive and they’ve very funny to me,” Hubbard said. Fitzhugh’s parents were divorced by the time she was 2 and her mother didn’t have much contact with her. She went to a girls school and then to Bard College in New York. The parallels are obvious.

“If you walk around a city at night, New York or Paris or London, you can see inside people’s apartments, and you get a glimpse into their lives and a story emerges.”

What’s different about Harriet is she’s coming out of that period when everything revolves around her. She’s interested in other people’s stories and lives. “Adult readers didn’t like it” when it came out in 1964, Hubbard said. “Harriet is not a model citizen. Some people said she was a gossip. She’s a rule breaker and she’s mean to her friends” in the notebook she has with her all the time. There, she writes down exactly what she thinks. “I think she was raised with no tact,” one audience member said.

But with all her flaws, Harriet remains true to herself, Hubbard pointed out. She doesn’t “improve” like so many children did in books from an earlier era. She is always Harriet, the writer.

Harriet’s parents are socialites who rely on a cook and a nanny, Ole Golly, to care for their child while they party late into the night. When it comes time for Ole Golly to leave, that sets Harriet spinning out of control. She gets meaner, then meaner yet, when her secret writings are discovered. She retreats into herself.

When Ole Golly writes to her after Harriet has lost all her friends, she tells her two important things, Hubbard said. “She has to lie and she has to apologize, and those are two things she does not want to do.” Ole Golly has always given Harriet the freedom to be herself, but she also gave her rules and boundaries, which go away when Old Golly goes to Canada to marry. “Without boundaries, she spins out of control,” Hubbard said. “And discipline is what all writers need. Harriet learns the power of words and how they can hurt. But you can tell,” once she’s allowed to write for the school newsletter, “she’s going to learn to use words for good.”

Hubbard said author Judy Blume was her kind of woman. She wrote stories about real people. In comments in the anniversary edition of “Harriet the Spy,” Blume confesses, she, too, wanted to be a spy or a detective. Another author commenting on the book, Rebecca Stead, said “Harriet the Spy” is about the emergence of a writer; writers have a desire to be part of other’s lives. Harriet sets off the desire to know about what other people are doing and saying.

Betty Mickle said she had a hard time with Harriet being so mean, and the mean things she wrote, but Mickle pointed out Harriet loves Sport, her best friend, in spite of what she writes. Hubbard suggested Harriet didn’t have the tools to make things right until near the end of the book.

Hubbard said it’s a book about loneliness “and there’s a difference between loneliness and solitude. Solitude is peaceful, solitude is what writers seek.”

When Harriet is given a chance to write about the sixth grade, she’s awed and horrified when she sees her words in print, just like other writers, Hubbard said.

So “Harriet the Spy” is much deeper and more full of meaning than what appears at the surface. It’s a lot for a child to take in. Hubbard invited audience members to revisit books they loved as children and see how they hold up, see what they really mean.

The next book in the Summer Reading Challenge is “Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer,” a nonfiction piece of history that Hubbard’s husband, Steve Cobb, will discuss. He and others in the group said it is a fascinating read. Don’t miss the chance to talk about it on July 29, a Tuesday, at 7 p.m., back at the Norvell Theatre. Hubbard thanked Piedmont Players, Reid Leonard, Josh Wainwright and Clyde for donating the space and being host.