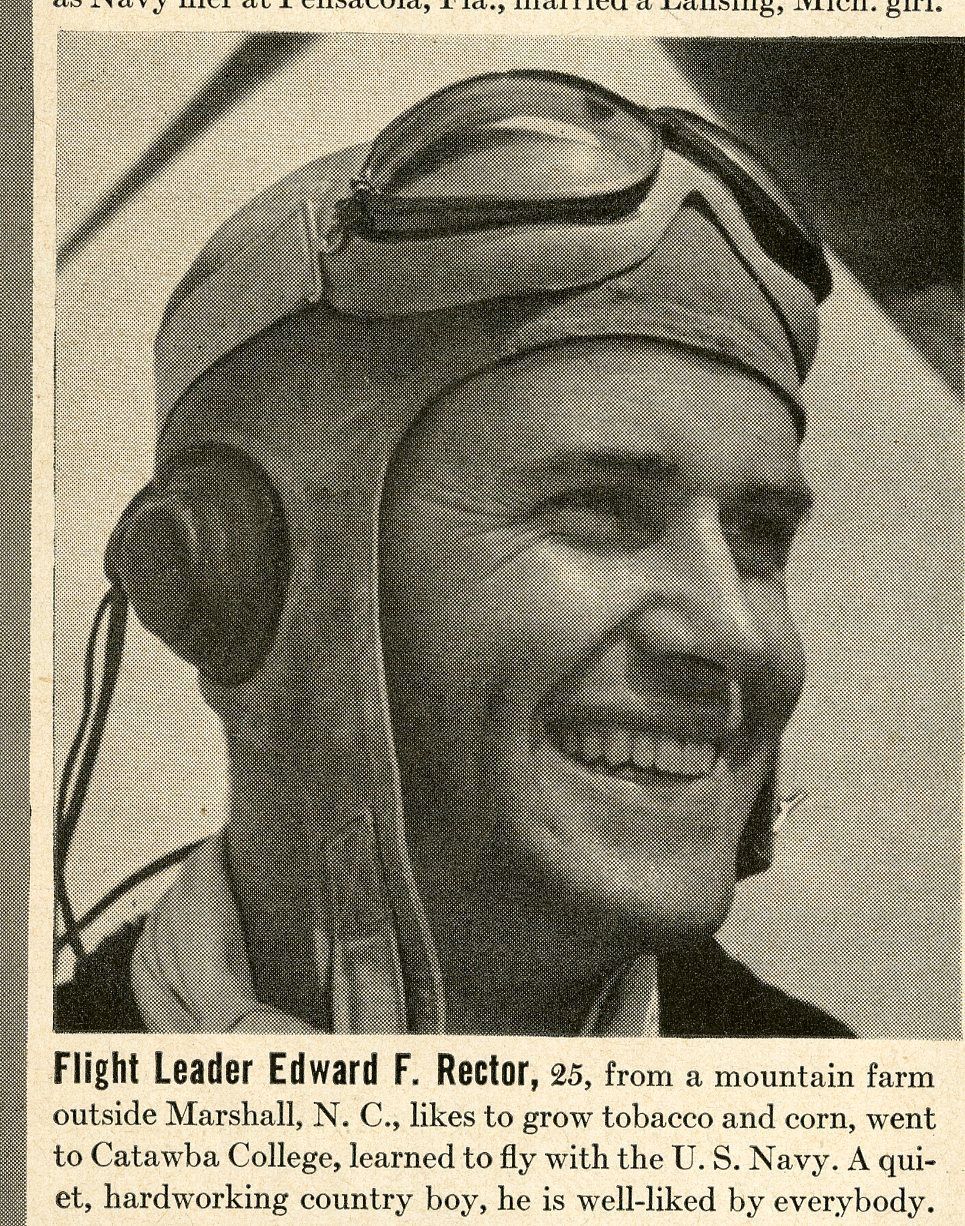

Flying Tiger: Catawba star went on to become WWII hero

Published 12:00 am Thursday, July 17, 2014

The Catawba football team departed Salisbury on Thursday, Sept, 23, 1937, for a Saturday game in Allentown. Pa., against the Muhlenburg Mules.

There were 28 Indians on board a Queen City Coach Company bus, including a 6-foot-2, 180-pound senior center/guard named Edward Franklin Rector.

Rector had come to Catawba three years earlier from the North Carolina mountain town of Marshall, and he waited tables to pay for school. The seventh of 10 children, he was quiet and shy when he arrived in Salisbury, but football changed him. It gave him confidence.

Most of the 1937 Indians had nicknames. Captain Charlie Clark was known as “Ole Joe” for some reason. Speedster Sam Pritchard answered to “Duck.” The the other ballcarrier was Dashin’ Don Peiffer.

The Indians’ pass-grabbing whiz was Maney “Trader” Horn, while the blocking back in coach Gordon Kirkland’s single-wing attack was George “Cowboy” Henderson.

Rector had been known as “Husky” in high school. At Catawba he was nickname-less, but everyone knew he was a guy they could count on, on both sides of the ball. He was polite off the field, but he became a “cold fury,” one writer reported, immediately after the kickoff.

Catawba engaged in a physical fight with Muhlenberg in front of 2,500 fans. A Clark-to-Pritchard scoring pass keyed a 7-6 victory, and the underdog Indians, coming off a 5-5 season, headed home 1-0. The Indians remain 1-0 against the Mules all-time. There’s never been a rematch.

Catawba’s second game in 1937, a 20-0 victory over Newberry, was keyed by the defense. When Rector and guard Jake Briggs were finally given a breather, with a minute to go and victory assured, Catawba fans rose for a standing ovation for two members of what would become known as the “Stone Wall Line.”

The Sailors of Newport News had no chance against Catawba in Game 3. Rector intercepted a pass and dragged tacklers down to the 5-yard line to set up a touchdown in a 21-0 romp.

In a 32-19 win against Roanoke, Rector’s biggest moment was blocking the PAT attempt that preserved a Catawba lead.

Catawba stuffed Guilford 28-0 on homecoming and throttled Western Carolina 14-0 to move to 6-0.

That set up a clash with Elon, and 5,000 fans surrounded Shuford Field to see it. Unfortunately, Catawba made negative history. The Indians managed just 23 yards of offense, still a school record for futility 77 years later, and lost 22-2.

Catawba got back on track by whipping Erskine, a victory that led to a confrontation with Appalachian State that would be played on a Friday night in Hickory. Catawba was 7-1. Coach Kidd Brewer’s Appalachian squad was 7-0-1, had not been scored on, and was hyped as the state’s last unbeaten team.

Rector led Catawba’s defense to new heights, and that Nov. 16 game should’ve ended in a 0-0 tie.

It was still scoreless with 12 seconds left, and Appalachian went into punt formation on its 10-yard line. Catawba tried desperately for the block, and that was a mistake. The punt was faked, and Earl Henson, who starred in Boone in baseball, basketball, soccer and track as well as football, was suddenly sprinting behind a wall of blockers. He went 90 yards to hand Catawba a crushing 6-0 loss.

While Appalachian would not be scored on that regular season, Catawba had to move on to play its biggest rival — Lenoir-Rhyne — on Thanksgiving Day. It would be the final game for Rector and Catawba’s seniors.

The rivalry was serious. L-R students sent Catawba a coffin by express mail, with spaces reserved for the Indians’ stars. An airplane dropped leaflets on the Catawba campus reminding everyone of the score of the previous year’s game — a 6-0 victory by the Bears.

Catawba students weren’t entirely innocent. The previous fall they’d kidnapped Lenoir-Rhyne’s mascot — a live bear. They transported the beast from Hickory to Salisbury by truck, but they did return him unharmed the day of the game.

The most memorable moment of the 1937 game came when a Lenoir-Rhyne guard named Joe Persianoff slugged Pritchard and got himself ejected.

The game came down to a goal-line stand by the Indians when L-R had first-and-goal at the Catawba 2. It was Rector who broke through the Bears’ line on first down and made the tackle for a 2-yard loss. Catawba got the stop it needed to win and finish 8-2.

Rector was that kid who sailed paper airplanes around classroms growing up and he was fascinated by the eagles soaring in the Blue Ridge Mountains.

He wanted to fly. After high school, he hitchhiked a day and a half to Langley Field in Virginia, trying to become a pilot. But he was sick and he was rejected.

If not for that rejection, he never would have enrolled at Catawba.

Rector’s attempt to emulate the eagles met with more success after his 1938 graduation from Catawba. By the summer of 1939, he was a naval aviation cadet. He was a natural. After 10 hours of instruction, he was soloing. He trained at Anacostia, Md., and earned his wings in Pensacola, Fla.

He was assigned to a dive-bomber squadron. He served on the carrier USS Ranger for a year and on the USS Yorktown a few months.

War had been raging for many years between Japan and China, and Rector was intrigued when the opportunity came to get closer to that fight. He joined the American Volunteer Group being organized to fight against the Japanese in China and Burma.

Rector signed up not just for the excitement but for the extra pay — $600 a month, twice what he was making as a naval ensign. On top of that, the Chinese government was promising a reward of $500 for every downed Japanese plane.

Rector explained his thinking to Bob Bergin of Military History magazine — “When I heard about the AVG, I saw an opportunity to find out if I was as good as I thought. To be paid a fabulous salary and a bounty for each plane destroyed sounded heaven-sent. I jumped at the chance.”

Rector was from a fighting family. His father had been in the Spanish-American War. Uncles had fought in that war as well as the first World War.

Rector joined the AVG in June, 1941, six months before Pearl Harbor brought the U.S. into World War II. The AVG was a stealth operation initially. Rector stopped in Salisbury to see Kirkland and the Catawba football team before he left and told Kirkland he was headed overseas as an instructor.

By September, 1941, Rector had been transported by liner and freighter to a secret base in Burma and was learning from Gen. Claire Chennault about aerial combat with Japanese fighters and bombers. Rector was one of 90 pilots trained to fly P-40 Warhawks. The planes would in time be identifiable by their distinctive shark-mouth paint. The group would become known as the “Flying Tigers.”

The first combat action for the “Tigers” came 13 days after Pearl Harbor, on Dec. 20, 1941, when Japanese bombers struck at the Chinese city of Kunming.

“I saw my tracers going in, wingtip to wingtip,” Rector recalled in that interview with Military Magazine. “There was a tail gunner firing back at me as I came right up the tail, just shooting the hell out of him. As I climbed, I looked back. There was a flame from just aft of the pilot’s cockpit, streaming back 50 feet beyond the tail.”

That was the first official kill by the “Flying Tigers.” There would be nearly 300 confirmed kills in a span of six months, and probably there were many more. It was difficult to confirm downed Japanese planes that disappeared into water.

With everything negative in those first months after the U.S entered the war, the “Tigers” were important. They were the only source of good news. Twenty-seven Japanese planes were shot down on Christmas day alone. Two dozen “Flying Tigers” became aces — a pilot who had shot down five planes.

Rector sent two more planes crashing in flames on Jan. 24, 1942, and was on his way, not only to ace status, but to being featured in a Life Magazine article.

The “Flying Tigers” were disbanded on July 4, 1942, due to internal pressure to make the unit part of the conventional U.S. military. Rector, who had downed the first plane for the “Tigers,” also shot one down on their final day of existence. He had 6.5 kills as a “Flying Tiger,” A “half-plane” means two pilots shared the kill.

Rector stayed with the China Air Task Force, which followed, long after most of the Tigers were gone. He finally returned to the U.S. late in 1942 to be treated for a parasite infection.

He was honored in ceremonies in Salisbury in 1943. Kirkland joked that it was hard to get used to calling one of his former linemen, “Major Rector.”

Rector was assigned test-pilot duties in Florida for a time, but in the fall of 1944, he returned to China as commander of the 23rd Fighter Group.

Twice, he was listed as missing in action. Twice, he cheated death.

On one of those occasions, his fellow pilots saw him going down in flames. They drank gin to toast his memory, but the next night, Rector came riding out of the jungle on horseback, swinging a Samurai sword. Reports differ as to whether he rode a donkey, mule or horse, but all agree he was very much alive.

On Jan. 4, 1945, Rector was missing again. Six days later, he was reported safe.

He downed his last Japanese plane on April 2, a twin-engine bomber, bringing his confirmed total to 10.5 kills. That final kill came one day after he was promoted to full colonel.

In addition to surviving bullets, anti-aircraft fire and flames, Rector weathered bouts with pneumonia and malaria.

He came home to North Carolina with a barrel full of medals. Chennault pinned a Silver Star on him. China’s Gen. Chiang-Kai-Shek personally put a Distinguished Flying Cross on Rector’s chest.

Rector retired from the Air Force in 1962.

He was honored in Faith in 1991, 50 years after his aerial deeds with the “Flying Tigers.”

Catawba presented him with its Distinguished Alumni Award in 2000.

Rector was 84 when he died in 2001 after a heart attack. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.