Struggling for peace: Book explores religion, violence

Published 11:23 pm Friday, November 14, 2014

Religion News Service

In the West, the idea that religion is inherently violent is taken for granted by everyone from academics to cab drivers, says British religion scholar Karen Armstrong, the former Roman Catholic nun who wrote the best-selling “A History of God.”

Her new book, “Fields of Blood: Religion and the History of Violence,” picks at the presumably inextricable knot of religion and violence over the course of thousands of years of human history, scrutinizing even the peaceful intent of Jesus. We asked Armstrong about the Prince of Peace, human nature and the Islamic militancy roiling the Middle East and Africa. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: “Fields of Blood” begins in the primordial slime, with a discussion of the evolution of the human brain. What’s with the neurophysiology?

A: We do have these violent impulses deeply embedded in the core of our brain, and without them, our species would not have survived. When they get mixed up with the more reflective, rational parts of our brain, you get some of the worst catastrophes. You get Auschwitz — total violence done in a controlled, terrible, rational way.

Q: Why do so many people think that religion is inherently violent?

A: It’s absolutely burnt into our secular Western consciousness. The “myth of religious violence,” as it’s been called, developed in the 18th century and mirrored what was going on in the states that were emerging in Europe at that time: An absolute ruler had to be sole master of the state, and the church had to be relegated to a subordinate position. The myth developed that religion was so violent that it had to be kept out of politics.

Q: What’s the quick response to the person who says “religion is the root of evil” and “I don’t have time to read your 400-page book”?

A: I wrote the book to work out for myself why exactly that the pronouncement “religion is the cause of all violence in history” was so annoying to me. The relationship between religion and violence is complex.

But the quick response? The First and Second World Wars were not caused by religion. Stalin’s gulag was not inspired by religion. The Young Turks who massacred Armenians were ardent atheists. That stops them in their tracks.

Q: You find violence in every religion in your book. But can’t an exception be made for Jesus, the Prince of Peace?

A: Jesus could also be verbally abusive, according to the Gospels, though we have to remember that we have very few of Jesus’ actual words. All of these great founders were struggling in their own ways for peace, Jesus among them.

But I don’t see him as any more special than the rabbis who worked so hard to deal with the violence of Jewish Scriptures, or the Prophet Muhammad — the Quran is constantly talking about peace and reconciliation.

Secularism doesn’t get off the hook, either. We can’t sit around saying as soon as we separate religion and politics peace will break out. It just didn’t.

You think of the French Revolution. The only way to dismantle the Ancien Regime, they thought, was to demolish the church.

And this has happened in the Middle East, where secularization has proceeded so rapidly that it’s experienced as an outright assault. At the holiest shrine in Iran, the Shah shot hundreds of unarmed demonstrators, people peacefully protesting against obligatory Western clothes.

Q: Before you write about Jesus, the rabbis, or Muhammad in “Fields of Blood,” you spend considerable time on Ashoka. Why are you so fascinated by this ancient man most of us have never heard of?

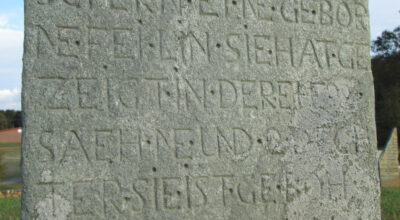

A: I wanted to call the book “Ashoka’s Dilemma” (after the king of India’s Mauryan Empire, who murdered his brothers to ascend to the throne in about 268 B.C. and became a Buddhist toward the end of this reign). He was appalled by the violence that he had seen, and he put up inscriptions throughout his realm pleading for more compassionate and peaceful governance. But he could never disband his army.

Had he done so, all these wannabe emperors would have started fighting each other and there would have been mayhem. Ashoka’s dilemma is the dilemma of civilization itself. No state, however peace-loving, can afford to disband its army.

Q: You ask us to look outside Islam to understand the attraction of Islamic militancy. Are recruits to the Islamic State not interested in Islam?

A: All of them are not fired up by Islamic zeal. Two of them who left Britain in May to go to Syria ordered from Amazon a book called “Islam for Dummies.” Some of them are young people who feel bored and that life is meaningless. This is something we have to take very seriously instead of just blaming it all on Islam.

Of the 9/11 hijackers, only one of them had a deep knowledge of the Quran. I looked at the research on them and the so-called lone-wolf terrorists, such as the Boston Marathon bombers, and found that only a fraction of them had a regular Muslim upbringing. Many militants only start reading and studying the Quran when they’re in prison.

To paraphrase forensic psychiatrist and former CIA officer Marc Sageman, no wishy-washy liberal: The problem with Islamic terrorists is not Islam, but ignorance of Islam, and a Muslim education might well have deterred them.