Writer illuminates the ordeal of Chilean miners

Published 12:00 am Sunday, January 25, 2015

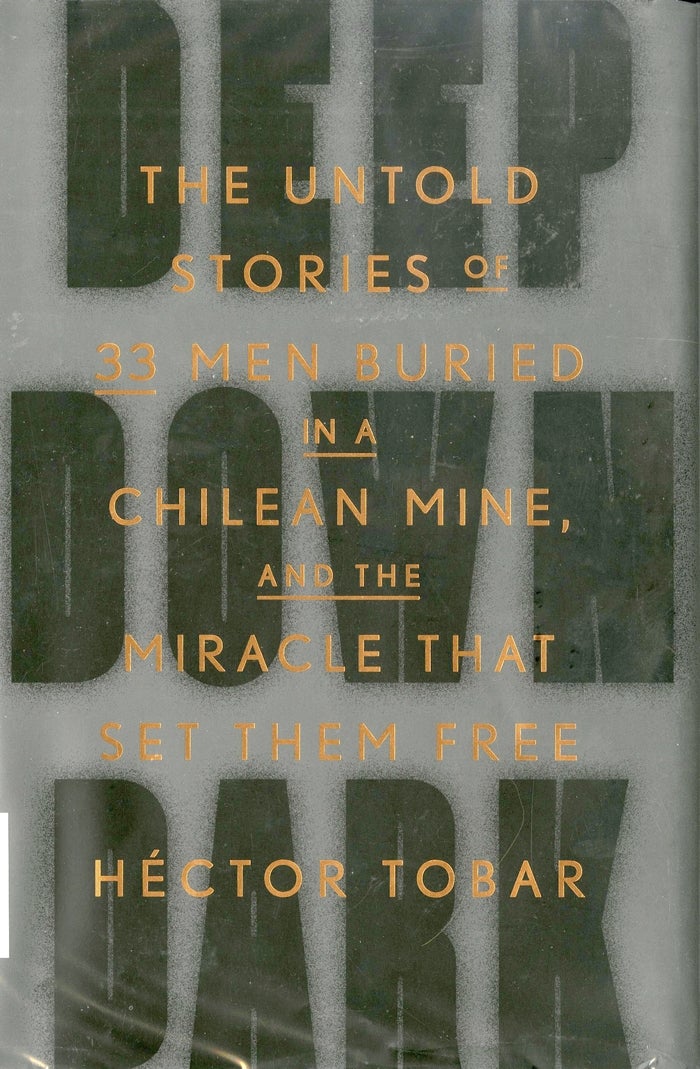

“Deep Down Dark: The Untold Story of 33 Men Buried in a Chilean Mine and the Miracle That Set Them Free. By Hector Tobar. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York. 2014. 306 pp.

By John Whitfield

For the Salisbury Post

In August 2010, the attention of the world was captured when reports of a mine disaster in Chile began to appear. Thirty-three men were missing and efforts were begun to rescue them or recover their bodies. Sixty-nine days later, the men emerged, gaunt, weak and weary but rejoicing with their families and friends who awaited them.

The men were nearly half a mile underground and the process which was undertaken to reach them was presented daily through the media.

What went on for the men during those 69 days has not been addressed, however, largely due to a decision they made before rescue that they would tell their story to only one writer. Hector Tobar was the writer selected and this book is their dramatic and inspiring story.

The author starts by telling who the men are, why they work in this dangerous occupation and what their dreams are. He describes their home life, their wives and/or girlfriends (for one miner named Vonni the two live only a few houses apart), their children and their activities outside of the mine. Rather quickly the reader comes to recognize and know these men as individuals, not just one of a group.

It is helpful in understanding the situation that Tobar tells something about the mine. There are pathways dug through the side of a mountain, pathways wide enough to accommodate large trucks. It is about 4 miles from the surface by truck to the breakroom where the men were eating lunch when the collapse occurred. This room, called the “refuge,” was stocked with some drinks, cookies and first aid supplies.

Nearby there was a tank of brackish water designed for use on machinery which was marginally drinkable though tasting like oil. It was not completely dark since the miners had lanterns and there was a truck parked close to the “refuge” which provided some light.

According to information given to Tobar by the men months later, the initial reaction is what one might expect. Some displayed panic and fear, some wept and some went to explore possible escape routes. A few men raided the food machines until the shift supervisor, Luis Urzua, managed to stop them. He recognized the need to ration their resources, telling them it may be several days before help arrives.

Gradually the first few hours passed, then the first few days. Some men continued to seek a way out while others sat and waited. This led to arguments between the groups and tempers began to flare up. In a dramatic move, Urzua took off his white hat and declared that he was no longer the leader. He urged them to work together as a unit, to make decisions as a team. They responded well and Tobar goes into much detail about the benefits of this action.

A second change for the miners came a few days later. Mario Sepulveda, a Jehovah’s Witness, felt the need for prayer. He approached Jose Henriquez, a Catholic, and asked him to pray for the group. He did lead prayers daily and more and more men joined in. Henriquez became known as the “pastor” and the others admired his half-remembered Bible stories. Their religious experience led the men to become more hopeful that God would save them.

What do 33 men do trapped for over two months? Tobar goes into much detail about this: writing dairies, leaving notes, dealing with nightmares or thinking over their pasts. Several tell of regrets over their “sins” and resolve to stop using alcohol or be more faithful in marriage.

Week by week their desperation increases but then, good news: They hear the sound of a drill. Their rescue is described, and the final chapters are about Tobar’s extensive interviews with the men and their adjustment to newfound freedom. It was not all easy: They experience worldwide acclaim, requests for money, travel, nightmares and other issues related to their trauma.

Tobar answers such questions as: Will the “pastor” continue to preach? Will Yonni live with his wife, his girlfriend or both? Will Urzua put his white hat on again? Will the men go back to the mine?

This is an interesting, thought-provoking book, sad, happy and very real.

The reader almost has to ask: If I were in that mine, what would I do?