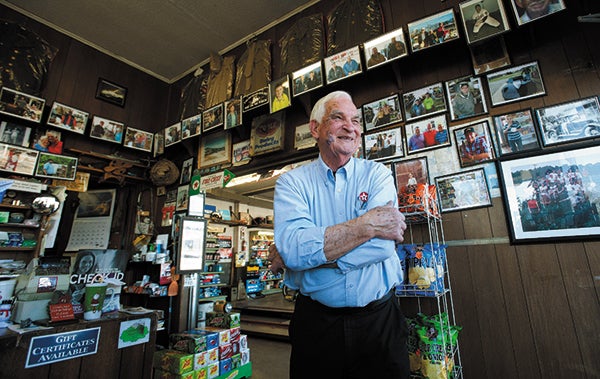

Price of Freedom founder Bobby Mault: ‘Everybody knew I was a runner’

Published 12:00 am Sunday, February 22, 2015

- JON C. LAKEY / SALISBURY POST Bobby Mault and his wife Ruby man the long time Maults Bros. on NC Highway 152. Bobby Mault is well known in the communty for his appreciation for the local veterans and worked for years to bring his vision of a military museum for Rowan County. In 2006, Mault was able to use the circa 1930's Patterson School as location for his dream. on 1/20/15 at in China Grove, NC, .

CHINA GROVE — Mary Smith pulled up to Bobby Mault’s service station, and it was a matter of seconds before Bobby pushed through the side door and greeted her as she stepped from the car.

Mault, 80, still pumps the gas for women, elderly and disabled customers. While he filled up her car, Mary walked inside to visit with Bobby’s wife, Ruby.

When Bobby returned, they all talked a little bit about Mary’s late husband, Cyrus, recalling his days as an Army ROTC student at Clemson. Mary donated Cyrus’ military uniform to the Price of Freedom Museum founded years ago by Mault. It’s housed in the 1936 Patterson School.

“I’ve got it in the Army room right now,” Mault assured Smith, describing how she could find the uniform on her next visit by looking past a new mannequin inside the door.

If you ever stop in at Mault’s service station in the wedge of N.C. 152 and N.C. 153, you get a better understanding of this man — this force — behind the unique military museum off Weaver Road.

Cyrus Smith’s uniform is one of more than 800 donated to Price of Freedom, which also is filled with photographs, military artifacts, books and memorabilia from World War I through Afghanistan.

About every day it seems, someone walks into the service station with a piece of their family’s military history for the museum.

Mault has never asked for anything, nor has he ever paid for anything related to the museum. It all has been given voluntarily and he considers it on loan. He has filled the old school’s cafeteria, and each branch of the military has a big classroom to itself filled with exhibits he has designed.

“I walk through the whole museum at night, and I just can’t believe it,” Mault says. “The Lord gave me the vision and furnished me with all these fine folks.”

Mault has even bigger plans — soon to be realized — for creating a three-room house, depicting how a home might have looked during World War II. He envisions the school auditorium as a place for community gatherings and concerts, while mixing in news-reel type interviews of local veterans.

To date, 9,000 fifth-graders from the Rowan-Salisbury School System have visited Price of Freedom on field trips. Mault likes to think he has created a “learning museum.”

Thousands of other people have attended special events — 9/11 remembrances, Veterans and Memorial days — in addition to the normal Sunday afternoon hours the museum is open.

Mault knows about perseverance, dedication, loyalty and love. He and Ruby have been married 61 years. He has run a service station for 60 of those He still works 80 hours a week at the station, not counting the 12 hours a week at night he’s at the museum building his exhibits.

Over the years, he also has been a China Grove alderman and manager of the Fellowship Park at Five Forks. For many years at the station, Mault planted and tended to 800 petunias in the triangle where N.C. 152 and 153 come together, and inside that birthday cake of patriotic colors he displayed a wooden replica of the Iwo Jima statue.

His flagpole at the station always flies the Stars and Stripes.

As a teenager, Mault ran the projector at the China Grove movie house. And as an adult, he helped to establish New Hope Presbyterian Church and was the man behind its annual four-night “Journey to Bethlehem,” when the church grounds were transformed into the village of Bethlehem at Jesus’ birth.

The living production would attract upwards of 7,000 visitors a year and required 115 participants. Mault recruited the people, designed and built sets and handled details such as lighting, music and props.

Now he devotes the same kind of energy to the Price of Freedom museum and probably will until he dies.

“He has always had a project,” Ruby says.

•••

The amazing thing about Mault’s devotion to the museum and the veterans who find it so enthralling is that he never served in the military.

As the Korean War was winding down, he was among 75 young men in China Grove who received their draft notices at the same time. He took his physical examination with the other guys, passed and went home, waiting for the call to report.

It never came. While everyone else received their marching orders, Mault didn’t hear a thing. When his first child was born, he returned to the draft office, asking what had happened.

The government had no record of his having been drafted or examined. All of his paperwork was lost. He ended up being reclassified and was never drafted.

“I think to this day I was left behind to do the museum,” Mault says.

Born to Robert and Irene Mault, Bobby was the youngest in his family of four brothers and two sisters. Bob and Irene’s first child, Robert, died when he was about a year old.

“Bobby” — their seventh child after Robert — was said to look exactly like him as a baby.

His father, driving the youngest Mault home from the hospital, told Irene, “You name him anything you want to, but he’s going to be called ‘Bobby.'” So it has stuck for 80 years now, even though Bobby’s real name is Charles Lewis Mault.

•••

Bobby Mault was a handful at first. When he was starting in the first grade, his mother would take him to China Grove Elementary School, but inside he would run through the hall, go out the school’s back door and be home before Irene returned.

“Everybody knew I was a runner,” Mault says.

Some of his most vivid childhood memories are as an 8-year-old, when three of his older brothers — Jim, Ray and Claude — were serving overseas in World War II.

“I know when the phone would ring my mom and dad would not want to answer it,” Bobby says.

Daily during the war, Mault would wait on the wall outside of his China Grove home for Mr. Freeze, the mailman, hoping for letters or word from his brothers. Each of them had close calls.

Jim’s B-24 crashed once on a South Pacific island landing strip when its tires were shot out by a Japanese sniper tied to a tree. Jim was OK, and one day the mailman delivered a wooden box with that Japanese soldier’s sniper rifle in it.

That rifle is displayed today in the Price of Freedom museum.

Ray survived his destroyer’s being hit by enemy fire in the Mediterranean. Claude’s tanker and ammunition ships also took hits, but he made it through without being injured.

Things grew tense at home because months would go by without Bobby, brother Ed, their sisters and their parents hearing any word from the three boys. It left a lasting impression on Mault.

•••

Bobby and Ruby starting their courtship as juniors in high school, and Bobby gave her an engagement ring as a graduation present in 1953.

They married that same fall and today have two grown children, Cindy and Jeff, and two grown grandchildren. All had their turns working at the service station.

By 1954, Bobby was 19 and in business for himself, operating an Amoco station just up the road from his present spot. Bobby and Ed, a Korean War veteran, then built and opened their Mault Bros. Texaco station in 1965, starting 48 years of being in business together before Ed’s death.

“We had a unique understanding,” Bobby says.

Ed was mostly the mechanic, while Bobby managed everything else. They took turns inspecting and greasing cars. They each had separate doors they were responsible for locking at night.

Ed had a favorite bench at the garage into which he carved a place to set his bottles of Cheerwine. Their father had worked for Cheerwine for almost 50 years, from 1913 to 1962, and when they were infants, he would soak one of his fingers in the cherry soft drink and rub it on their teeth, just to make sure they had a taste.

Bobby has filled the station with Texaco model trucks, airplanes and service stations. Scores of framed photos of his customers, friends and families cover the walls, weaving among the racks of chips, peanuts and crackers.

Above the pictures, closer to the ceiling, many donated military uniforms are still hanging, as they did throughout the station before Mault secured the school building in 2004 for his museum.

There’s a reason. Mault never says anything about the museum unless one of his customers brings it up first, usually with a question about the uniforms on the wall. That way, he’s not driving his regular customers away by constantly talking about Price of Freedom..

A uniform belonging to the late Dan Ritchie, whom Mault had looked after when he became sick, was the first uniform that Mault put on display at the station.

People would come in, ask about it, then declare with each new uniform added, “Well, if he brought his in, I’ll bring mine.”

Mault says he became the impetus for cleaning out many basements, closets and attics.

•••

It took 18 years of asking the school board before then County Commissioner Gus Andrews helped Mault land Patterson School, which had been used by the school system for storage after it closed in 1976.

“When a door closes on me, I don’t try to kick it open,” Mault says. “But when it did come open, I was ready.”

Frank Albright, a friend from their high school days in China Grove, was in the station the day Mault learned he could lease Patterson School for free over the coming 50 years.

“How about being my partner?” Mault asked Albright, even though the men had never discussed Mault’s dreams for the school. On that day, Albright officially became a co-founder.

“I just had that feeling,” Mault says about Albright, now deceased, and other people he has quietly recruited over the years. “I look for dedication.”

Mault filled the cafeteria first with all the uniforms, photographs and artifacts he had collected over the years, and the museum opened at the school in 2006. One by one, the classrooms have been added.

Mault becomes emotional when he thinks of all the children who have gone through the museum and seen the pictures and uniforms of their grandparents.

Certain spaces in the museum also become touching memorials to military veterans, young and old, who have died.

“I’m a great believer in planning,” Mault says. “You’ve got to have a vision or a goal, and you have to sacrifice something to reach the goal.”

Mault seems to be grooming volunteers Joel Honeycutt and Bobby Harrison for the future, giving them insights into how the museum should operate 20 years from now.

Honeycutt fell in love with the museum and started bringing Mault photographs he had taken at military air shows.

“Every event I came to,” Honeycutt says, “I knew something exceptional was happening at the old schoolhouse.”

Honeycutt recalls working at the museum one Sunday afternoon when two D-Day veterans who landed at Utah Beach on the first day of the Normandy invasion came to look around.

Honeycutt says it gave him goosebumps listening to their World War II stories.

“At the end of the day, Mr. Mault told me, ‘Sometimes we work, and sometimes we follow and listen.'” Honeycutt says. “That has always stuck with me because you never know what you are going to hear when someone walks through those museum doors.”

The Price of Freedom museum is located at 2420 Weaver Road, China Grove. It is free and open to the public from 3-5 p.m. Sundays and by appointment.

Contact Mark Wineka at 704-797-4263, or mark.wineka@salisburypost.com.