Tracking an outlaw: Davie County hunted Campbell after he killed 2 officers in 1975

Published 12:10 am Monday, June 8, 2015

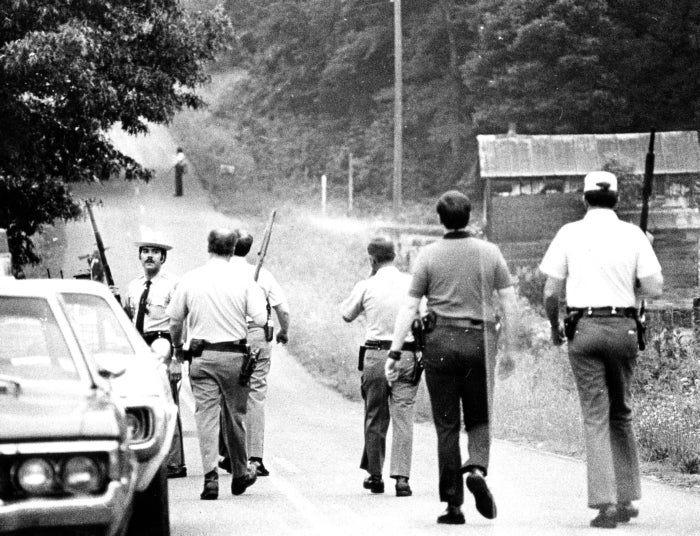

- salisbury post archives Davie and Forsyth officers search for Morrey Joe Campbell after he shot and killed two deputies on Friday, May 30, 1975.

By Beth Cassidy

Enterprise Record

It was a Sunday afternoon in the early summer. Mitchell Davis went into an old tobacco barn to use the bathroom, and as he was turning to leave, he realized he wasn’t alone.

There was a man crouched on a tier pole in the top of the barn, watching him.

Friday, May 30, 1975, around noon …

President Gerald Ford wanted the US to become less dependant on foreign oil. A man could buy a polyester suit from the local Belk store for $39.88, and rib eye steaks were just over $2 per pound.

Mood rings and pet rocks were all the rage, and the movie Jaws was about to be released.

It was four days after Memorial Day, and folks were winding up a short work week.

Morrey Joe Campbell ate lunch with fellow workers at the Heritage furniture plant, where his job was to sand cabinets and do small work with a screwdriver. Campbell, 29, had been married for about six years and had three small children.

Six weeks prior, he had been stopped for operating a car while intoxicated, which angered him. During the stop, he pointed a gun at the Deputy Wayne Gaither but Gaither and Campbell’s passenger were able to talk him down, and two weeks later, a judge ordered Campbell to undergo psychiatric treatment. He was scheduled to appear back before the judge on June 11 with his psychiatric report.

He never made it.

Friday night …

Campbell spent part of the night with his family, eating ice cream and watching television, but before dark, he was back out, driving his 1964 Ford to a service station at Farmington Road and N.C. 801, less than half a mile from the home he rented with his wife, a few houses down from where his parents lived.

Around 11 p.m., on Redland Road, blue lights appeared in his rearview mirror. Once again, he was being stopped for driving while intoxicated, and once again, it was by Deputy Wayne Gaither.

This time, there was no talking Morrey Joe down.

As Gaither approached the Ford, Morrey Joe shot and killed him, then sped off.

Gaither was 29, the same age as his killer.

Jessie Hodson’s husband, Keith, reportedly saw Gaither fall. Keith died almost 11 years ago, but Jessie, 90, still lives in the house where they were when they heard the shots and witnessed the horror.

“We were terrified” she said. “We heard the shots, I’m not sure how many, but it was pretty frightening. Nothing ever happened around here, and then that.”

Phillip Beauchamp, Sr. is gone also, but his son, Phillip Jr. and daughter Anna recall their dad was coming home from somewhere and saw what he thought was a car accident. He turned around, and he and another passerby found Gaither lying on his side in Donald Tucker’s driveway at 789 Redland Road.

Tucker’s windows were open to let in the cooler night air, and his two young daughters were asleep in the front room when he heard what he thought were firecrackers.

“I went to the front door and looked out, and I could see the patrol car with the blue light still going around and the windshield shot out.

“Then I saw Wayne. He was lying on his side about halfway up our driveway, and I started to go out, but another man was out there taking his pulse and he said ‘No point coming out. He’s dead.’ There were no cars or anything else around, Morrey Joe was already gone. Judy and I both remember it so well. There’s no way to forget it, especially when a body is in the driveway and a car all shot up with the light still going around,” he said.

The SBI came and drew a white chalk line around Gaither’s body, and Tucker said he remember it stayed there in his driveway for quite awhile, until the rain washed it away.

He had trouble explaining to his girls why it was there.

What would make a man shoot a police officer?

Gaither was known as a dedicated lawman, fair, honest, and a fine fellow. The Vietnam veteran was married and had been working in the narcotics division of the sheriff’s department. Campbell was suspected to be involved in narcotic activity.

Rumors were rampant at the time.

Others speculated a motorcycle accident 11 months prior to the shooting left Campbell with personality changes. At the time, Josie said it would take him a long time to answer her if she asked him a question, and she said he felt like people were against him. His supervisor at work also noted a change in Campbell’s attitude, saying his work attendance was erratic and he wasn’t getting along with co-workers.

A neighbor of Campbell’s at the time said he was being harassed by law enforcement.

But whatever the reason, Campbell wasn’t done.

Friday, 11:10 p.m. …

Forsyth Deputy R.L. “Buddy” Russ was on duty with his partner Jack C. “Red” Renigar, a reserve deputy. The two knew each other well and often rode together. They had just finished clearing a wreck off Peacehaven Road when one of the highway patrol officers there told Russ he’d heard on the radio shots had been fired at an officer in the area.

The dispatcher told Russ the suspect’s vehicle was heading toward Forsyth County on U.S. 158 or I-40, so he and Renigar went to Middlebrook Drive and U.S. 158 to watch for the car.

“We sat there several minutes when the car hadn’t come through, and we thought maybe we’d missed it or that he (Campbell) was on I-40. Red wanted to stay a little longer, and just before I decided we should leave, we spotted the vehicle going back toward Davie County, not the way we thought he would be. I pulled out behind him, and by the license plate, I knew it was Morrey Joe.”

Russ activated his blue light and Campbell abruptly stopped his car in the middle of the road, with Russ about 35 feet behind him. Russ told Campbell through the PA system to get out of the car slowly with his hands in the air, and Campbell’s door opened slightly, just enough that Russ saw what appeared to be the muzzle of a gun. Renigar was out of the car with a shotgun pointed at Campbell’s car, and suddenly, Russ said, there was a muzzle flash, and Renigar began firing at Campbell’s car. Russ fired about five shots from his service revolver at the left rear wheel of the Ford, and the sixth shot hit the rear windshield.

And then the Ford began to move.

Slowly.

For miles, at speeds no more than 45 mph, the agonizing chase went on, and when Campbell entered Davie County, just west of 801, he hit a car that was backing out of a driveway, but he kept going, turning onto Redland Road at the opposite end of where he’d killed Gaither just a short time before.

Campbell stopped his car near Andy’s store, and Russ saw him run from his car.

“He disappeared into the darkness toward the woodline behind the big white house near the corner. We lost sight of him,” Russ remembered.

Renigar got out of the car and opened the back door to get more ammo, and Russ heard a gunshot. At first, he thought Renigar had fired at Campbell, but when he called to his partner, he got no answer.

Renigar had been shot once in the head and died instantly.

Russ stayed on the scene for hours, his partner’s body covered with a sheet, where it would stay until the SBI had processed the scene. Russ knew Gaither from when the two took a course together at Forsyth Technical Community College, and he asked another deputy that night if Gaither would be coming to the scene, having no idea he had been shot earlier in the night. The deputy told him the news.

At some point the next morning, he said, his wife received a call that Renigar had been shot and Russ was “lost.”

“I don’t think they realized the negative impact that call had,” Russ said, choking up. “It was pretty heart-wrenching to me to know she went through that.”

He never found out who’d made the call.

Later that morning, Russ called his wife himself, telling her he was okay. At that point, he’d been without sleep for about 40 hours and kept vigil over the body of a man he knew and respected, all the while maintaining a calm that even now he isn’t sure how he managed, but when he heard his wife’s voice, he fell apart.

Forty years later, Russ said then and now, he cannot understand why Renigar was the one shot when he was mostly concealed by the car and Russ was out in the open.

“Maybe Morrey Joe saw Red as more of a threat since he had a shotgun and I had a pistol. I was 25 years old, and Red was 42. He wasn’t even supposed to be on duty that night because he was going on vacation the next day, but one of the other reserve officers wanted off and Red offered to take his shift. He was a reserve officer and not getting paid, and I was.

“He was there that night free and doing someone else a favor. He was married and had three children. I have asked myself many times over the years why him and not me. And I have gone through in my mind a million times what I could have maybe done differently that night, but the only thing would have been if I had called in sick and not gone to work. I can’t think of a single other thing I could have done differently that would have resulted in a different outcome,” he said.

Russ describes his partner as having a great personality, never abrasive, very friendly and soft spoken, never raising his voice.

“He was a Christian man, a family man, and he loved his family very much. I spent the rest of Friday night and the next day looking for Morrey Joe.”

He wasn’t the only one.

By midnight, the word was out that a killer was on the loose, and as people locked their doors and armed themselves, law enforcement officers spanned out across much of the county.

One of them was Robert Cook.

Cook was 25 years old, a former Davie deputy working in Kernersville as assistant police chief at the time, and he got the call two officers had been shot. He helped clear the big white house near Andy’s store, somewhere Campbell was believed to be, but the home was empty.

Cook knew where Campbell’s sister lived and went there, to her mobile home that was up on blocks.

With him was Andy Stokes, a young highway patrol officer. Cook said Stokes opened the trunk of his car and handed his shotgun to him. It was dark but Cook saw the silhouette of a man in the light from a window of the mobile home. Up in the window was a woman who cried out, “Don’t kill him.”

Campbell said to Cook, ‘I’ll get you before you get me,’ and Cook shot toward Campbell, hitting him in the knee. But Campbell crawled under the trailer and made his way into bushes at the back of the property. No pursuit was made because Campbell’s reputation as being someone who could throw a walnut into the sky and shoot it before it hit the ground was well known, and Cook said the decision was made not to risk any more lives that night. Bloodhounds were brought in but lost the scent.

May 31, Saturday …

Stokes was 29, a highway patrol officer, and was dating the woman who would become his wife. After working the early shift Friday, he went home but heard on the radio an officer had been shot, so he and another trooper set up a road block on U.S. 158 Friday night, but Campbell never made it to that area.

The next morning, joined by hundreds of officers from all over the region, Stokes remembers going house to house, sometimes being let in by the homeowner and sometimes kicking in a door or breaking a window to gain entry.

“The remarkable thing is we never received a single complaint. We were searching for a pretty desperate character and people were glad their properties had been cleared,” said Stokes, now Davie’s sheriff.

All morning, the search continued, with law enforcement officers and civilians elbow to elbow, all armed.

At 3:30 that afternoon, history was made.

On a petition by Solicitor H.W. “Butch” Zimmerman Jr., Judge Thomas W. Seay Jr., a Davie County Superior Court judge, declared Campbell an outlaw, giving anyone, law enforcement or civilian, the right to kill Campbell without prosecution if he didn’t surrender.

“That declaration was reserved for only the most desperate situations,” Stokes said. “I believe he was the only person ever in Davie County to be declared an outlaw, and he was the last person in North Carolina to be declared an outlaw.”

During the afternoon search, something happened that still makes Stokes chuckle.

There had been a report that Campbell was spotted in some woods near a plowed field. Stokes said a large amount of men lined up at the front of the field and began making their way down it, suspecting at any moment they might be ambushed.

Tension was high.

Suddenly, a gunshot rang out, and Stokes said everyone hit the dirt.

Except for one man. His gun had gone off accidentally.

“That poor guy was the only one left standing,” Stokes recalled. “I felt so sorry for him, I know he was embarrassed.”

Around 7 that night, after hours of slogging through fields and woods muddied by the rain that day, the foot search was called off.

Morrey Joe Campbell was still on the run.

Thunderstorms rolled in.

Sunday, June 1 …

Mildred King woke up in the Spillman Road home she shared with her husband, Wade. She had no idea what had been going on just a few miles from their home, but after a deputy banged on their door and was let in by Wade, they were told of the situation.

Amazingly, she said, she and their three children were still allowed to leave their home to go to church. Wade stayed behind to talk to the deputies.

Anna Beauchamp, whose father found Gaither in the driveway 35 hours earlier, said when she woke up Sunday morning for church, she was shocked to see a row of police cars in front of her house on Spillman Road, with deputies splayed across the hoods and roofs of the cars with their guns trained on a field.

“My dad made us go to church because he wanted us out of the neighborhood. He knew it was dangerous for us to be there. So we went out through all those deputies, and we were afraid at any minute they might start shooting,” she said.

But there would be no more gunfire.

Dogs, armed men in pickup trucks, armed men on foot, and men in helicopters all searched for Campbell. A triangular perimeter bordered by N.C. 801, Spillman Road and Farmington Road had been drawn, and lawmen were fairly sure Campbell was within that perimeter.

Earlier in the day, a tobacco barn had been searched and cleared.

Around 5 p.m., Mitchell Davis told his partner, John Henry Hicks, chief deputy in Yadkin County, that he needed to use the bathroom. Davis’ retelling of what happened next is chilling.

“I went into the barn and there was some hay on the floor at the back of the barn. I went back there and urinated on the hay, and when I turned around to come out, I saw him sitting up in the top of the barn on a tier pole, watching me. I didn’t say a word. I walked out and told John Henry, ‘Well, if he’s been here, he’s gone now,’ and we walked clear of the barn. I told John Henry then, he’s in there. John Henry wanted me to shoot him but I said ‘No, he didn’t shoot me so I’m not gonna shoot him.’ ”

Davis called for backup, and the SBI quickly arrived, lobbing tear gas canisters into the barn. Campbell came out the door, unarmed and with a thin rope around his neck that led some to speculate he tried to hang himself. He was wrestled to the ground and taken without incident to the county jail in Mocksville.

Stokes was among the men who surrounded Campbell when he came out of the barn, and he remembers the way Campbell looked.

“He had an evil demeanor, just looked like the personification of evil,” Stokes said.

Davis said he could tell Campbell wanted to run but knew there was no way to.

“He was done running at that point. I never heard him say a word,” Davis said. “I have no doubt if he’d had a gun at the time, he would have shot me.”

Campbell’s rifle had been found Friday night.

Stokes said people lined Main Street to see Campbell brought in, and people drove up and down the street, horns blaring. Campbell was taken to the Davie hospital, where he was treated for a shattered knee and a flesh wound on his arm. Late Sunday night, he was transferred to Central Prison in Raleigh.

On July 13, 1976, Campbell was sentenced to 80 years on each count of second degree murder. A psychologist who testified at the trial said Campbell was found to have a first grade reading ability, a second grade math ability, and an IQ of 59, deemed to be “moderate mental retardation” but Campbell was found competent to stand trial.

For 17 years, Campbell remained imprisoned in Raleigh, but on Thursday, July 30, 1992, at 7:40 p.m., he was found hanging from a shoestring in his cell.

Efforts to resuscitate him failed, and he was pronounced dead at 7:55 p.m.

A promising life and career cut short

Wayne Gaither had just been assigned as a plain clothes narcotics officer with the Davie County Sheriff’s Department. He had completed a two-year police science course at Forsyth Tech, hoping to become a member of the SBI.

Then, at age 29, he was shot to death by Morrey Joe Campbell.

A native of the Sheffield community of Davie County, he was a 1964 graduate of Davie High, served in the U.S. Army in Vietnam, and worked in the private sector before joining the sheriff’s department in 1971, then for the Mocksville Police Department.

The day of his death, Gaither had gone about his business as usual, co-workers said. About 9 p.m., another officer said that calls came in that Campbell was “raising hell.” Gaither stopped a car operated by Campbell just before 11 p.m.

“He was a good officer — good in working with narcotics,” said then Mocksville police officer R.W. Groce. “He was doing a job in this county that no one else has done.”

“There wasn’t anyone any better,” said then Mocksville Officer Gary Edwards, who worked with Gaither on narcotics cases. “He was a fine fellow to work with and would do anything you asked him to. He was well thought of throughout the department.”

“He knew what he was going,” said Deputy Steve Stanley, who also worked undercover. “He knew the law but he was quiet with it. He didn’t push anybody around.”

“He was an excellent officer,” said then Sheriff R.O. Kiger. “Wayne was dedicated to his job and liked what he was doing.”

At his funeral at New Union United Methodist Church, the Rev. Kermit Shoaf said: “We all know Wayne loved what he was doing. Wayne chose this way to show his love for his friends.”