No ‘Watchman’ for me

Published 12:00 am Sunday, July 19, 2015

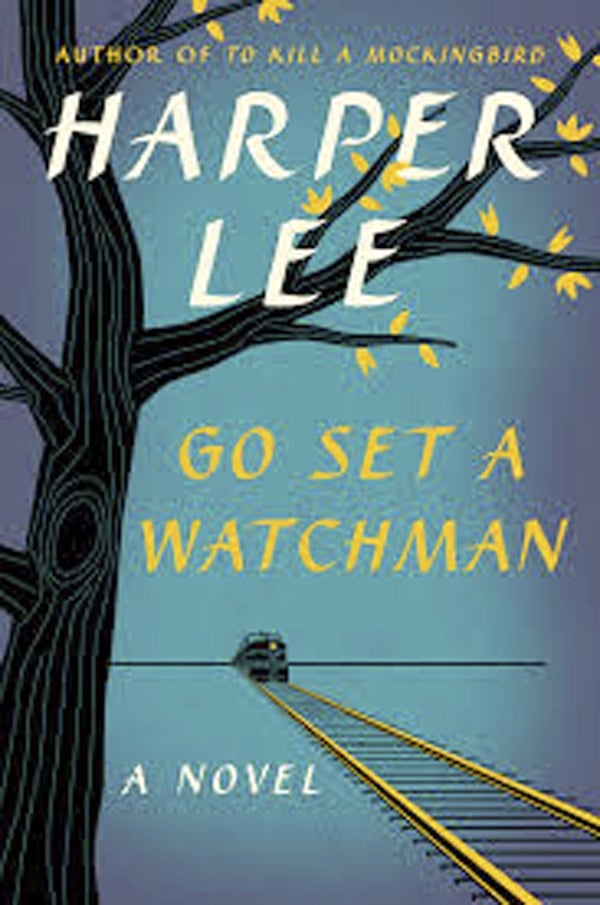

I don’t want to read “Go Set a Watchman.”

It was never intended to be published. It is a rough draft from which “To Kill a Mockingbird” was crafted.

And make no mistake, it was crafted, by Harper Lee and her editor at Lippincott, Tay Hohoff.

This is not meant to question Lee’s talent, but to point out that many, if not most writers have first novels or drafts of novels that were never meant to see the light of day. Ask them. The first attempts were weak or overdone, had weird plotting or cardboard characters.

Those early efforts are the writer learning his or her craft, trying out their talent, trying to organize thoughts and ideas, using all sort of tidbits stored up in the brain or in journals or in newspaper clippings.

Writers have a gift of absorbing what they see and turning it over in their minds, or remembering single events that had no special meaning, but could be made into something else. It is only with time and experience that writers begin to come into their gift.

Susan Vreeland, author of a number of historical fiction novels, said it when she was the Brady Author Symposium speaker at Catawba College several years ago. She told students they had to live and have different experiences, to observe before they could become writers.

And young writers change over time. Follow any author and you can see how their writing evolves, how it gains depth and scope.

The reviews, and they are few at this point, of “Go Set a Watchman,” indicate the writing is rough, the characters a bit over the top, the situation melodramatic.

“To Kill a Mockingbird” certainly has drama, vivid characterization and dark secrets.

“Watchman” is told from the perspective of Jean Louise (Scout) coming back to Alabama from New York City to find her aging father, once her hero, an angry bigot and professed racist. We are all shocked. The intimation is Lee was writing what she knew, and there’s truth in that. Alabama remains a place where the races have, at best, a fragile relationship.

Brother Jem is apparently dead in this early version.

And that’s what “Watchman” is, an early version; it’s not a prequel or a sequel or a new novel. It’s the bare bones of a different story. Hohoff saw the bones and suggested where flesh was needed. Did Lee agree with her strong-willed editor, who was a proponent of Civil Rights?

She must have, to some degree — “To Kill a Mockingbird” was published. It earned enormous acclaim and is held up to this day as great American writing about a subject no one would talk about.

Lee disliked fame and endless questioning. Could it be because Hohoff was so much a part of the finished work?

This book was not edited, not even copy-edited much. And believe me, copy editing is not book editing. It’s not meant to be. Lee has a new agent, new publisher and new attorney.

“Watchman” is an unedited early work by a writer who had her fame and then valued her privacy. Some question that attorney, Tonja Carter, for unearthing the draft and pushing an elderly Lee to have it published. A new round of unwanted fame? More intense questions about her true beliefs? A destruction of Atticus, the man readers have come to admire, even idolize?

It will earn money, no doubt about it. Will Lee live long enough to find some benefit from that? Or will this feed the national malaise and line the pockets of everyone else involved in its publication? The timing is rather unfortunate.

And I, for one, do not wish to be part of the frenzy.