In ‘A Full Life,’ Jimmy Carter at 90 remains a wise truth teller

Published 12:00 am Sunday, July 26, 2015

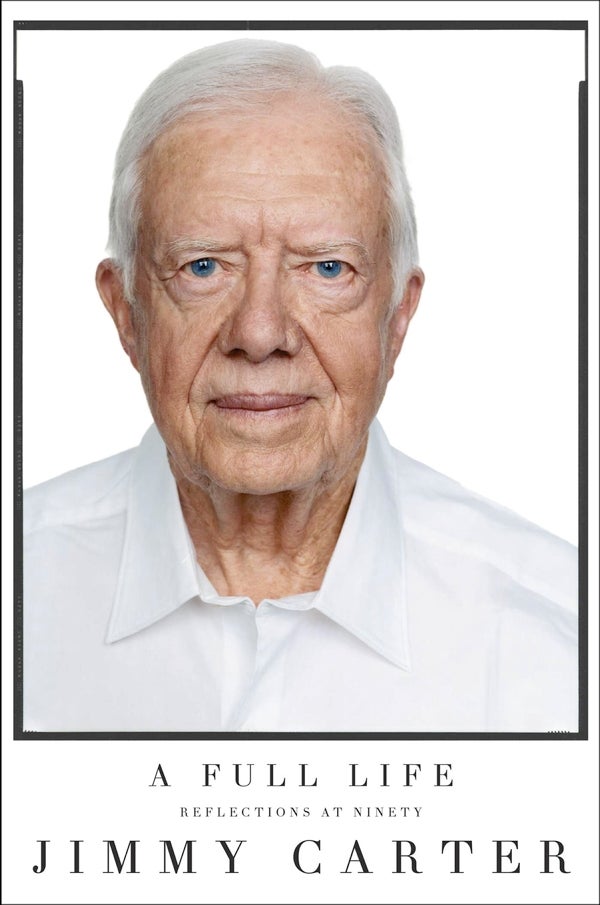

- Jimmy Carter's "A Full Life: Reflections at 90" is a warm and detailed memoir of his youth followed by a clear-eyed assessment of the issues he tackled as president and afterward. (Photo courtesy Simon & Schuster/TNS)

By Carolyn Kellogg

“A Full Life: Reflections at 90” by Jimmy Carter, Simon & Schuster. 272 pages. $28.

Jimmy Carter let me down. Not with his book “A Full Life: Reflections at 90” — a warm and detailed memoir of his youth followed by a clear-eyed assessment of the issues he tackled as president and afterward — but with his response to the question “Does the arc of history bend toward justice?”

“I’m not sure about that,” said Carter, who has spent the last 35 years advocating for peace. “I think we reached the high point, in the practical aspects of justice for most people on earth, when we passed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. After World War II, about 1948, every country committed themselves to permanent peace with the establishment of the United Nations and then the Universal Human Rights declaration. I think we’ve gone downhill in many ways since that time.”

I was hoping for some kind of hopeful reassurance. But instead he pointed out that “violence and destruction and hatred and animosity and discrimination seem to me to be becoming more acceptable in some parts of the world.”

This refusal to sugarcoat matters is quintessential Carter; he has maintained all the acuity and principle of his youth while accruing the wisdom of his 90 years.

One challenge of Carter’s presidency was that he spoke the truth, even though during his years in the White House (1976-80), the truth was often bad news. He faced an energy crisis, a capsizing economy, opposition from Congress, and the revolution in Iran than led to American hostages being held captive 444 days.

Carter revisits some of those challenges in the book, in chapters titled “Issues Mostly Resolved” and “Problems Still Pending.” Resolved issues include swift and cogent sections on Rhodesia, the B-1 bomber, “Saving New York City and Chrysler,” and the Cold War — he doesn’t take credit for its end, but it gives him a chance to talk about his landmark SALT II Treaty. Among “Problems Still Pending” are drugs, special interests, the threat of nuclear war and intelligence agencies. He doesn’t let Ronald Reagan, George H.W. or George W. Bush or Bill Clinton off completely, but when they appear, his language about them is carefully neutral.

“I try not to be critical of others who’ve done differently from me,” Carter says by phone, “but in a positive way spell out the things that might be done more effectively, more honestly, more beneficially to our own people and people in the rest of the world.”

Historian Julian E. Zelizer, professor at Princeton University and author of the 2010 biography “Jimmy Carter,” is convinced that presidents’ memoirs rarely do much to change how people remember them. “I don’t think all of a sudden people will think the late ’70s were better than they thought,” he says. Yet he believes Carter is working to change perceptions. “I think there’s a part of Jimmy Carter that feels he wasn’t treated well and people didn’t understand what he was trying to accomplish.”

Carter has clarified his positions before, in more than two dozen books that include memoirs of his presidency, the controversial 2006 book “Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid” and, most recently, 2014’s “A Call to Action” about the rights of women. In “A Full Life,” in addition to providing a sweeping overview of a broad range of issues and frequent credit to his wife Rosalynn, he remembers his pre-political past, including surprisingly detailed stories about tilling a field with a mule at the family farm in Plains, Ga., and an incident when, as a sailor, he was swept off the deck of a submarine near South Korea and almost carried off to sea.

At the heart of the book is a message that Carter has carried through his political life: “My hope is that our leaders will capitalize on our country’s most admirable qualities,” he writes. His version of those qualities, deeply informed by his Christian faith, seems far from our current foreign policy. “We need to be a Superpower as a champion of peace, not war; we need to be a Superpower in being a champion of basic human rights, although we’re now violating a good many of the basic principles of human rights,” he says. “We need to be the most generous country in the world; the most dedicated to the essence of democracy and freedom.”

When pressed, the avowed truth teller admits that we have a long way to go. “Most people on earth look on our country as the number one proponent of war. Since the Second World we’ve invaded or bombed about 30 nations in the world…. But I think that we should be a champion of peace, and a champion of human rights, and a champion of democracy, and a champion of freedom, a champion of generosity, a champion of environmental quality.”

Carter added, “Those things won’t cost us anything. They will add the admiration, and support, and I think ultimately the economic benefit to our country.”

In many ways, the American public has caught up with the issues Carter championed during his presidency. Zelizer says Carter “took a risk by dealing with human rights and energy in 1979 and paid a political price for it.”

Yet losing the presidency to Reagan led to Carter’s subsequent life as an international statesman, for which he won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002. Now he’s one of the Elders, a group of independent leaders founded by Nelson Mandela that negotiates at the highest levels on issues of peace, development and the environment. “Nelson Mandela was a very close friend of mine….” Carter says. “That’s one of the benefits of the life that I have, that is, access to almost anyone in the world with whom I want to meet and discuss issues.”

In June and July, Carter has undertaken a coast-to-coast book tour with a schedule ambitious for someone half his age. “When I write a book, it gives me a unique chance to speak out around the nation,” he says. Unlike others of his stature, he doesn’t go on the lecture circuit. “Going on book tour is the best chance I get to express my views to a pretty wide audience.”

In “A Full Life,” Carter puts the long arc of his story together the way he sees it. The book includes his accomplishments as a negotiator and peacemaker in the humblest way — as a man who was at work on a larger project, something he continues to be. A primer for the generations who don’t know his work and a personal retelling for those who do, “A Full Life” may herald the reappraisal he deserves.