Remembering a Christmas long ago: Neil Morrow teaches children about veterans’ sacrifices

Published 12:00 am Friday, December 25, 2015

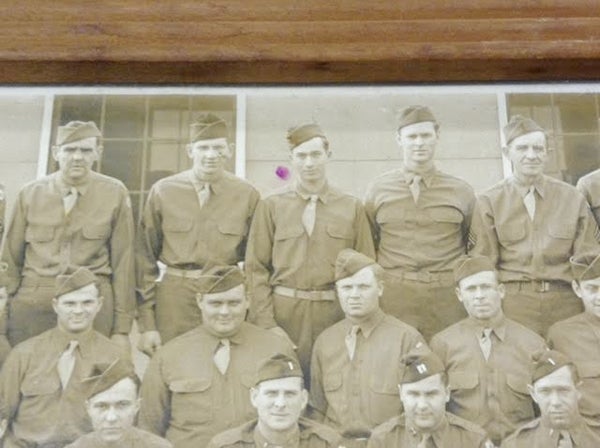

- Neil Morrow, top row middle, before leaving for Europe and World War ll.

By David Freeze

For the Salisbury Post

Rowan County native Neil Morrow likes to stay warm these days. He enjoys time in front of a big window next to his wood stove. Now 93, Morrow has found a new purpose in educating Rowan County’s fifth-graders about his service during World War ll.

Just married and at the age of 20, Morrow joined other U.S. Army draftees in Salisbury in the fall of 1942 on the way to basic training at Camp Croft, South Carolina. Morrow said, “I always thought I would end up in the infantry carrying a rifle. But they gave us a written test and I became a truck driver.”

Next stop was truck driver training at Fort Lee, Virginia. The truck was more like a farm tractor with a big trailer behind. With an open top cab, the driver was exposed to any weather conditions. Morrow’s trailer was loaded with tents and supplies at Kansas City, Kansas, and prepared for maneuvers in Tennessee. He said, “There were engineers, infantry and Air Force all there. The airplanes flew over and dropped bags of flour to simulate bombs. My truck never got hit.”

On to Illinois, where Morrow’s unit of 12 trucks spent the 1943-44 winter and got their first taste of frigid conditions. It was during this winter that Morrow excelled as a sharpshooter, scoring 198 out of a possible 200. He said, “Most of those truck drivers couldn’t have hit this house.”

The spring of 1943 found Morrow on the way toward the war in Europe. With their trucks already shipped ahead by rail, Morrow’s 291st Division rode the train to New York before catching an old freighter to cross the Atlantic. Morrow said, “We had a small room underneath the top deck. They had made bunks out of pipe. We had no real bathrooms or drinking water. We couldn’t come up on deck for a while, but when we did, there was nothing to see but ships everywhere. Some were gasoline tankers and others were hauling airplanes.”

During the 13-day trip, most of the soldiers were seasick. With no hot food, those who could ate K-rations. Finally in sight of land, German submarines torpedoed two gasoline tankers, one on each side of the convoy. Morrow said, “The ocean looked like it was on fire. The English Channel was burning.”

Training for the upcoming Normandy invasion followed. Fields upon fields of equipment waited for use as the allied armies geared up for some of the fiercest fighting of the war. Morrow and his unit were issued half-tracks, trucks with tank treads on the back that would be loaded on landing craft capable of hitting the beaches.

Once engineers and bulldozers had prepared the Normandy beaches, Morrow’s half-track and one more were loaded with ammunition and gas cans and backed end to end onto a landing craft. After arrival at Normandy, the unit waited for at least a week while watching B-17 bombers flying in formation on the way to bomb St. Lo. Morrow said, “They came over like big clouds, closing off the sun. They came over with one formation at one altitude and another formation higher. We went back and forth taking supplies to the infantry moving toward St. Lo, France.”

Winter started to slow the allied progress and supplies struggled to keep up. Morrow remembers going to pick up a load of baled burlap bags. The bags were later filled with dirt and used as a bunker fortification for the soldiers, often stacked high enough to allow tarps to be suspended over them held up by poles.

The trucks carried their own gas and oil and the drivers were responsible for servicing them and keeping them on the road. A smaller unit of three trucks was commanded by a lieutenant. Morrow said, “He watched out for us. Sometimes we drove in the dark. We never lost a truck, but we saw some shot with 1,000 holes.”

As Christmas drew nearer, the trucks were sent to pick up turkeys and bread for Christmas dinner. Morrow remembers, “We got back and couldn’t get the turkeys to the soldiers. It was so cold, as low as 30 below zero, and foggy. We put pine brush around the underneath of the trucks and made out OK. We couldn’t leave the trucks unless we could follow our tracks to get back. Sometimes the snow was waist deep. Remember there were no cabs on the trucks.”

“Somehow the turkeys got unloaded, at least a thousand of them. I must have been asleep when they were unloaded. The weather stayed socked in for weeks, all through Christmas. This was 71 years ago this week.”

Morrow recalled the frigid conditions at the Battle of the Bulge. He said, “For nine months, there was no way to take a bath. There was no sweating anyway during the winter. Frostbite took hands, toes and feet. Sometimes the Germans would kill our guys and take their clothes. I saw the frozen bodies loaded in trucks. Hitler wouldn’t take prisoners. The highlights were the field kitchens. They had big pots of hot coffee, not good coffee, but we were glad to get it.”

As the weather eventually cleared, the allied planes were able to take out the big German Tiger tanks. The troops moved out and kept rolling, only stopping at the Rhine River long enough to set up a pontoon bridge. The trucks crossed the Rhine heading into Germany and hustled to keep supplies to the troops.

In April, Morrow was surprised to hear that he had been transferred to the 28th Division and was headed for Japan. Loaded onto a troop train, he was sent back to France. German prisoners gave haircuts before the soldiers pulled off their old underwear, got cold showers 12 inches apart with lye soap and received shots in both arms. Morrow said, “If those were medics giving those shots, I was an airplane pilot. We got clothes too, lucky to find something close to our size before being loaded on the ships for home.”

Back in Boston, Morrow and the other soldiers were treated to 24-hour food, anything they wanted. Morrow got a 30-day leave with orders to report next to Camp Shelby in Mississippi. He remembers, “Suddenly sirens were going off. We had just bombed Japan. The war was ending.”

After returning to Camp Shelby, an officer told Morrow that he could get out of the army if he wanted. Morrow said, “He told me that I had enough points by being at Normandy, the Battle of the Bulge and Rhineland. I thought it over and decided to head home.” Morrow was home to stay in August of 1945.

Once home for good, Morrow spent time working at Cascade Mills in Mooresville, doing some farming and electrical work before finding a lasting job at Fiber Industries. He said, “My wife wanted me to go there and the pay was good.”

Margaret Morrow’s health began to worsen in 1970. Diagnosed with myasthenia gravis, she couldn’t see. Other issues contributed to her death in 2001. Following her death, Morrow was a man on the move. “I have seen much of the United States. I kept my bags packed, just couldn’t stay home.”

But now, Morrow has found another home of sorts. He has spoken to 10,000 fifth-graders at the Price of Freedom Museum since its opening. With their own classroom, Morrow and Air Force veteran and neighbor Terry Ogelthorpe get a chance to share their military experiences. Museum founder Bob Mault said, “Neil hasn’t missed a class here. The children love him and the museum wouldn’t be what it is without Neil Morrow.”

Volunteer Ollie McKnight added, “Neil doesn’t meet a stranger. The children always write back and say how much they loved him.”

These days, Morrow spends much of his time baking pies to share with friends and neighbors. McKnight said, “He gave me one last year but I don’t have one yet this year.” Morrow is quietly planning a trip to New Orleans to a new military museum.

“The Good Lord stopped that war. He shut Hitler down,” said Morrow. But through his words, the sacrifices of Morrow and other veterans come to life for today’s school children, enriching both their lives and just maybe Neil Morrow’s as well.