Funny little stories in a funny little book

Published 12:00 am Sunday, January 3, 2016

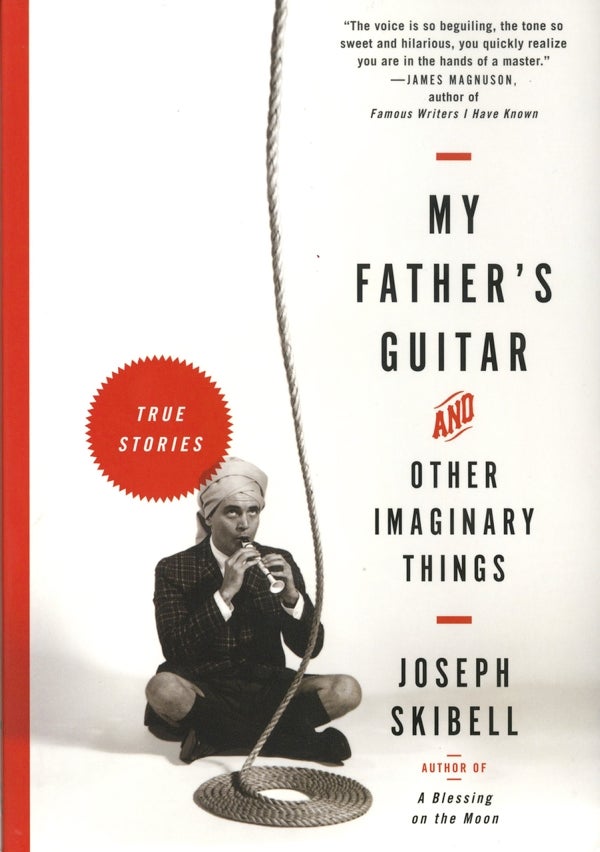

“My Father’s Guitar and Other Imaginary Things,” by Joseph Skibell. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. 2015. 209 pp. $16.95.

By Deirdre Parker Smith

deirdre.smith@salisburypost.com

On one of our recent rainy days, I picked up a funny little book and stepped into the world of Joseph Skibell.

His latest work is “My Father’s Guitar and Other Imaginary Things,” a collection of essays with a hint of fiction about incidents in his life. Much of the fiction is based on how unreliable memories can be.

Skibell is the author of the novels “A Curable Romantic” and “A Blessing on the Moon,” both of which earned critical acclaim, and other works.

These essays/stories were written after Skibell and his daughter went on a guitar tour, visiting master guitar makers. And that trip was prompted by a memory of his late father’s guitar. Or the guitar Skibell thought his father had, or was it one he had? A guitar anyway.

And somewhere in there, it probably had a lot to do with Skibell being 49 and his daughter 18 and that sudden feeling of “this IS what being a grown-up means.”

“A Blessing on the Moon” told a fantasy-realistic story about Polish Jews who died in the Holocast that won high praise from nearly every major review publication. “A Curable Romantic,” in which a man falls in love with two different prominent women of the 20th century, had a cast of hundreds, and Skibell wanted to write something intimate and close.

The stories, of course, are intimately about Skibell’s life, and it’s a quirky one. He’s a writer, a teacher, a student of ancient Jewish texts. His family lives in Texas, which seems unusual in and of itself, a Jewish family with a Texas drawl. And his family has its fair share of oddballs — like any other family.

In “Wooden Nickels” Tiger, Skibell’s uncle, is a less successful version of Ed Wood, trying to be a moviemaker and Hollywood somebody. He’s also got this great idea of building casinos on Indian reservations. None of it ever works out, of course, and Tiger dies sad and alone in an Alzheimer’s unit. But Skibell commits him to our memories.

In “Irvin and Wonderland,” Skibell spends a few days with his father in the hospital. Irvin Skibell is very somber, rather critical and uncomfortable when it comes to son Joseph, the writer. But a reaction to medication sends Irvin into a remarkable place, where he sees and imagines things, where he talks about his dreams and going into hyperspace, and speaks German and dips into Jewish mysticism.

For the first time in their lives, they are able to get along. But as the medicine is changed, life returns to normal. Those precious moments, though, live on.

And there are silly parts, too, like the house in Taos haunted by a dressmaker who committed suicide, the sound of scissors heard, then problems with water and electricity. And Skibell’s discussion with the happy man who locked his wheel with a boot for parking in a restricted parking lot.

Throughout these story/essays, Skibell is having fun. He’s letting his hair down, letting it all hang out and writing what’s on his mind, which is a fascinating and complex thing.

One of the funniest stories is “International Type of Guy,” his attempt to get telemarketers to fund a trip. Every time a telemarketer calls, Skibell turns the tables and tells them about his great idea: “I’m soliciting funds to send a delegate to the Eighty-Eighth Annual Esperanto Congress in Sweden.” Because, in addition to writing screenplays, novels and studying Judaism, he also learned Esperanto, the international language linguist L.L. Zamenhof proposed in 1887. You can read all about that in “A Curable Romantic.”

Not having read Skibell’s novels, this collection of memoir essays is a glimpse into what pleasures may lie ahead.