Where art and politics mix: ‘The Muralist’

Published 12:00 am Sunday, January 17, 2016

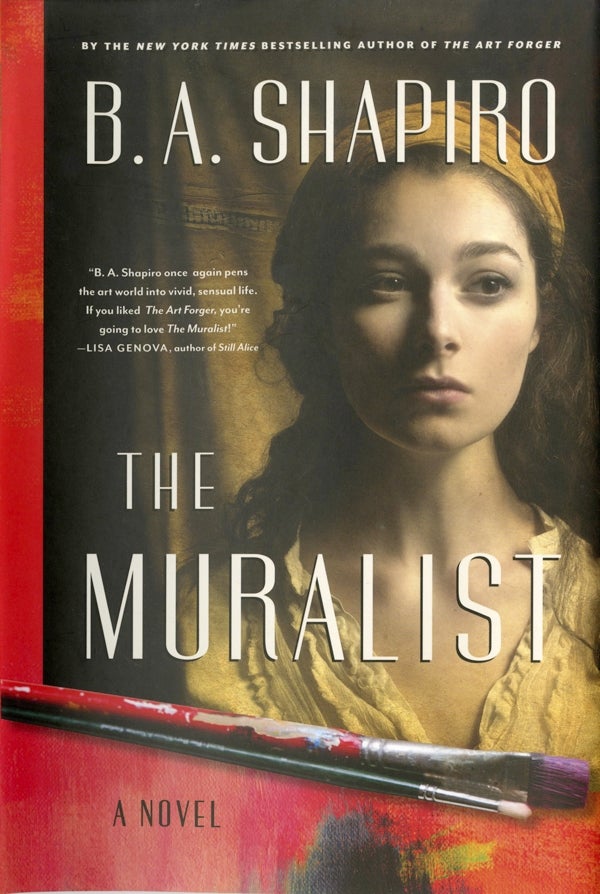

“The Muralist” by B.A. Shapiro. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. 2015. 337 pp. $26.95.

By Deirdre Parker Smith

deirdre.smith@salisburypost.com

“The Muralist,” with its blend of real and imagined characters, important world events and survey of abstract experssionism kept me turning pages, but left me a little frustrated.

It’s a story about artists who worked in the WPA, Works Progress Administration, on the cusp of America’s involvement in World War II. It involves Mark Rothko, Lee Krasner, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Alizée Benoit. Only Alizée is not real. She is the heroine of this story of emerging artists, America’s reluctance to enter WWII and the plight of European refugees turned away from the United States.

While the focus is on an artist and her passions, Hitler’s atrocities and America’s isolationist stance are a strong undercurrent.

Alizée is brilliant, undiscovered and extremely passionate about her art and her relatives. Author B.A. Shapiro takes liberties with the chronology of real events, but she packs the book with genuine concerns and a sturdy knowledge of art.

Her 2012 novel, “The Art Forger,” also featured a brilliant painter, but one who spent most of her time recreating great works of art.

Here, she imagines a missing link concept to categorize Alizée’s bridge to abstract expressionism, by having her paint in a style that blends realism with abstract expressionism.

One of the frustrations of the novel is that we cannot see what Alizée is painting, though it is richly described. Without understanding the works of the era well, the imagination can only go so far.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if Shapiro could have thrown in paintings by Rothko — in this fiction, Alizée’s lover — Krasner and the rest to give an idea of what Alizée’s works might be like.

Shapiro tells the story mostly in third person from Alizee’s fevered, paranoid, facile mind. She introduces Danielle, a modern art cataloguer working at Christie’s as Alizées great-niece.

Danielle, who speaks in first person, discovers four square canvases taped to the back of other paintings and tries to prove her great-aunt is the artist.

The problem is, Alizée disappeared in 1940 after a two-day stay at a sanatorium, never to be heard from again. As far as Danielle knows, only two of her works survive, works once owned by Eleanor Roosevelt.

So, yes, there’s plenty of big names here.

And here’s another one — Breckinridge Long, who was the U.S. State Department official in charge of European refugees. He was known as an extreme nativist with special suspicion of Eastern Europeans. Many have blamed him for the deaths of tens of thousands of Jews denied refuge in the United States.

In “The Muralist,” Alizée joins a group trying to remove Long from office so refugees will be allowed into the country. Part of the story is the dangerous plan they concoct.

There’s a lot going on here.

There was a real Jumble Shop where artists from the group met regularly to drink and talk, and there were murals being commissioned through the WPA’s Federal Art Project, which produced 100,000 paintings and murals and 18,000 sculptures, employing Krasner, Pollock, de Kooning, Rothko and many more artists who later achieved fame and critical acclaim.

Alizée’s story is engaging. Readers watch her transformation from young, hard-working artist to madwoman going to search for her relatives.

The chapters involving Danielle exist to affirm that Alizée was talented, and to tell the reader what finally happened, but a sole focus on Alizée would have worked better. We learn little about Danielle’s character.

The novel reads quickly, with plenty of dialogue, some of it overwrought.

Some will quibble with Shapiro’s shifting of events in time, and that can be misleading.

Still, it’s entertaining. Shapiro’s characters and plot are more complex than those in “The Art Forger” and you might learn something.