5 myths about Harriet Tubman

Published 6:08 pm Saturday, April 23, 2016

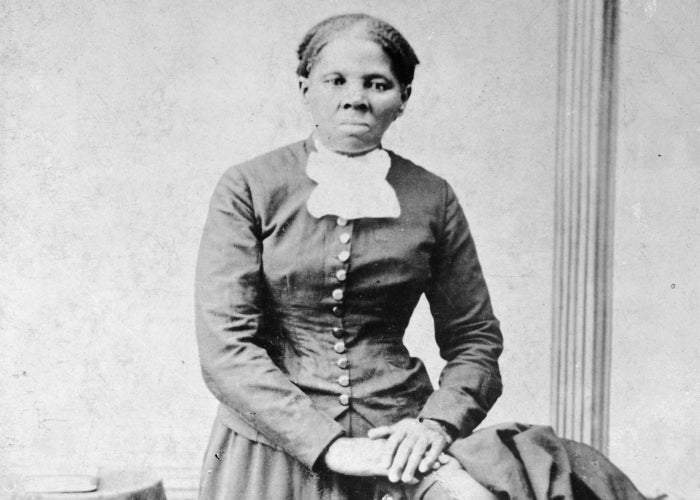

- This image provided by the Library of Congress shows Harriet Tubman, between 1860 and 1875. Tubman's likeness will be on the $20 bill, making her the first woman on U.S. paper currency in 100 years. (H.B. Lindsley/Library of Congress via AP)

By Kate Clifford Larson

The Washington Post

We think we know Harriet Tubman: former slave, Underground Railroad conductor and abolitionist. But much of Tubman’s real life story has been shrouded by generations of myths and fake lore, propagated through children’s books, that has only served to obscure her great achievements. The truth about the woman who will be the new face of the $20 bill is far more compelling and remarkable.

1. Tubman was the Moses of her people.

This is a common sobriquet for Tubman, popularized by an early biography written by Sarah Bradford. The phrase is typically used to conjure the enormous scope of Tubman’s efforts to lead fellow slaves to freedom. Bradford wrote that Tubman freed more than 300 people in 19 trips. That claim is repeated on plaques and monuments. But while Tubman is indeed a giant of American history, her Underground Railroad missions were more limited, though much more complicated and dangerous, than they are often made out to be.

Tubman told audiences repeatedly during the late 1850s that she rescued 50 to 60 people in eight or nine trips. Her first biographer, Franklin Sanborn, suggested that she, directly and indirectly, brought about 140 or 150 people North. My research has confirmed that estimate, establishing that she brought away about 70 people in about 13 trips and gave instructions to about 70 more who found their way to freedom on their own.

Contrary to some narratives, Tubman’s missions did not extend throughout the South. She returned only to Maryland — specifically to plantations on the Eastern Shore — to bring away close family members and friends whom she loved and trusted. It was too dangerous for her to go places where she did not know the people or the landscape.

Tubman didn’t start the Underground Railroad, as Treasury Secretary Jack Lew claimed this past week. She tapped into a well-established network and helped expand it, making it stronger and more effective.

2. Tubman, at the time of her work with the Underground Railroad, was a grandmotherly figure.

Tubman is often portrayed in popular culture — in art, monuments, picture books and living-history presentations — as a decrepit old woman. This reflects photographs taken late in her life, which, as Washington Post critic Philip Kennicott noted this past week, “have the effect of softening the broader memory of who she was, and how she accomplished her heroic legacy.”

In fact, Tubman was a young woman during the 11 years she worked as an Underground Railroad conductor. She escaped slavery, alone, in the fall of 1849, when she was 27 years old. A runaway advertisement at the time, offering $100 for her capture, described her as “of a chestnut color, fine looking, and about 5 feet high.”

She was also fierce. She carried a small pistol on her rescue missions, mostly for protection from slave-catchers, but also to discourage frightened runaways from turning back and risking the safety of the rest of the group. According to one story, she knocked out her own tooth with that pistol to stave off an infection that might have derailed a rescue mission. As a teenager, Tubman was nearly killed when an overseer hit her in the head with an iron weight, and she suffered from headaches and seizures for the rest of her life, but she didn’t let those slow her down, either.

Viola Davis is set to play Tubman in an upcoming HBO movie based on my book, and, in Davis’s portrayal, I think we will see the leader and warrior Tubman truly was.

3. She followed the quilt code to the North.

This myth is a staple of school curriculums. Students are taught that slaves and free people stitched secret, coded directions into quilts and then hung them outside at night to help guide freedom seekers to the next safe house. While it is a pretty story, it has no basis in fact, and it tells us nothing about the real heroes and actual workings of the Underground Railroad.

Most of the quilt designs claimed by proponents of the quilt code were not even created until after the Civil War and slavery ended. Enslaved people would not have had access to the multiple varieties and colors of fabrics needed to construct such quilts, nor would they have placed precious bedding outside when it would have been badly needed inside their homes. We also know that Underground Railroad routes changed frequently because of the danger involved, so permanent embroidery would have been of limited use, anyway.

Tubman depended on her great intellect, courage and religious faith to escape slavery and then go back to rescue others. She followed rivers that snaked northward, and used the stars and other natural phenomena to guide her. She relied on sympathetic people, black and white, who hid her, told her which way to go and connected her with other people she could trust. She wore disguises. She paid bribes.

When leading her charges, she would alter the tempo of certain songs, “Go Down Moses” and “Bound for the Promised Land,” or mimic the hoot of an owl, to signal whether it was safe or too dangerous to reveal their hiding places. She also used coded letters. In December 1854, for instance, she had a letter sent to Jacob Jackson, a literate, free black farmer and veterinarian, instructing him to tell her brothers that they needed to be ready to “step aboard” the “Ol’ Ship of Zion.” In other words, she was coming to rescue them.

4. Her work with the Underground Railroad was her most significant contribution.

While these activities made her famous, her service as a Union spy, scout and nurse during the Civil War, and her activism and philanthropy after the war, cemented her reputation as a remarkable American patriot.

In June 1863, Tubman became the first woman to lead an armed military raid when she guided Col. James Montgomery and his 2nd South Carolina black regiment up the Combahee River, routing Confederate outposts, liberating more than 700 slaves, and destroying stockpiles of cotton, food and weapons. It was of her service to the U.S. Army that she was most proud. She successfully petitioned to receive a veteran’s pension, and at her funeral in 1913, she received semi-military honors.

Tubman also was an ardent suffragist and began appearing at suffrage conventions before the Civil War, becoming more active as the 19th century wore on. She fought for civil and political rights for not only women and minorities, but for the disabled and aged, too, and she established a nursing home for African-Americans on her property in Auburn, N.Y.

5. Putting Tubman on the $20 bill is an insult, because she was anti-capitalist.

Feminista Jones laid out the case in The Washington Post last year: “By escaping slavery and helping many others do the same, Tubman became historic for essentially stealing ‘property.’ Her legacy is rooted in resisting the foundation of American capitalism. Tubman didn’t respect America’s economic system, so making her a symbol of it would be insulting.” After Lew announced that Tubman would indeed be on the redesigned $20 bill, feminist writer Zoe Samudzi told The Post, “I’m mulling over the irony of a black woman who was bought and sold being ‘commemorated’ on the $20 bill.”

While Tubman was adamantly against slavery, she wasn’t against capitalism. She flipped slave-based capitalism on its head by “stealing” her own body and those of others from its unpaid, unfree grip. Tubman was an entrepreneur: She created a laundry and restaurant near Hilton Head, Spouth Carolina, during the Civil War, where she taught recently liberated women to provide goods and services to the Union Army for pay; and later she ran several businesses from her home in Auburn, where she supported a house full of dependents.

The marginalization of women and people of color is not suddenly changed with redesigned currency. But Tubman on the $20 bill reinforces the message that the devaluation of women and minorities – economically, politically, socially, culturally and historically – is no longer acceptable.

Larson is the author of “Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman, Portrait of an American Hero.