For Powell, poetry forms in her head, waiting to be set free

Published 12:01 am Sunday, June 12, 2016

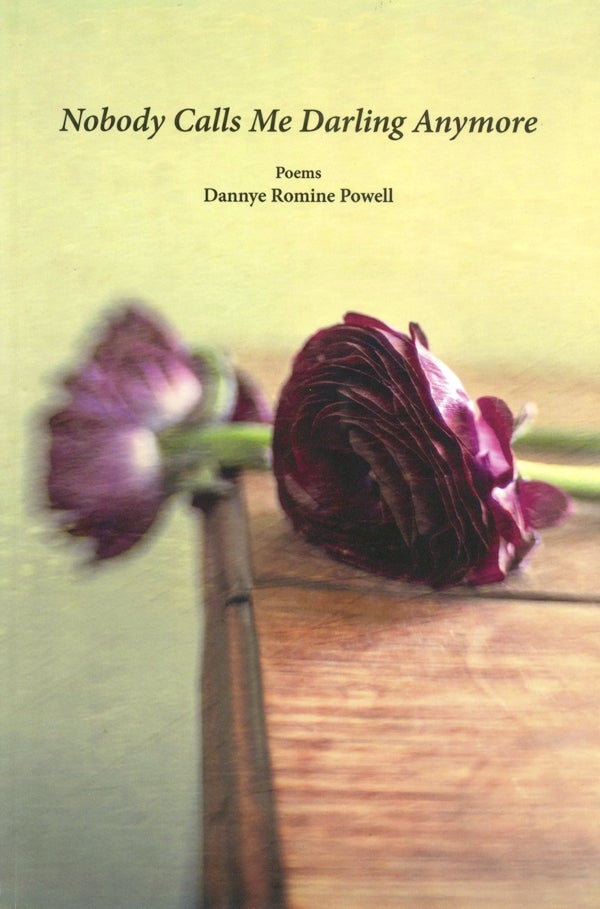

- Author Jennifer Hubbard and poet/journalist Dannye Romine Powell will talk about Powell's new book of poems, "Nobody Calls Me Darling Anymore," at the first discussion of the Summer Reading Challenge, Tuesday, 7 p.m., at Rowan Public Library.

By Deirdre Parker Smith

deirdre.smith@salisburypost.com

Poems come through her subconscious, says Dannye Romine Powell, a journalist and poet.

She doesn’t spend her days thinking up lines or metaphors. No similes simmer in the background.

It’s when she takes her laptop to bed on Thursday mornings that the poems come out. She releases them from her brain.

Powell will be the featured author at the first Summer Reading Challenge event next Tuesday, bringing her new collection, “No One Calls Me Darling Anymore.”

“I never have a poetic line come into my head unless I’m actually writing it. … I may do unconscious things that work for me and I trust it, but it’s not available to me when I’m in the newspaper office or babysitting. Maybe on a walk.”

“Most poets in the group would say that,” Powell said. The writing group is one that has been going on for more than 30 years, a rarity and a blessing for its members. They meet on Friday afternoons.

“We bring new work, critique it hard. Rarely is there a hurt feeling. There may be lots of ‘I just don’t get what you’re saying.’ We eat pie and talk about lipstick, but we really work hard.”

On Friday mornings, a group gathers at Powell’s house to read poetry.

This new collection, published in the fall of 2015, is very personal. “Several are about my mother,” who died a few years ago. “The title poem is about that. My mother is dead and now no one calls me darling anymore.”

There are also poems about her husband, Lew Powell, a journalist and writer, and other family members, one son who had trouble with alcohol, another son who didn’t cause trouble and doesn’t have a lot of poetry written about him.

“There are no poems about grandchildren! That’s taboo among my writing group — the editors will think you’re old.”

A lot of the poems are true, a lot of them are not, “but the essence is true.”

Powell has not written much lately because another family is living with them, including a 4-month-old and a 22-month-old.

“I have to go to McDonald’s and drink coffee to write. It’s a wonderful place to write.”

Powell’s path to poetry is different. As a young person, she wrote poetry, then she swore she would only write nonfiction until she was 30, then she started in her group. “It had poets in it, I heard their work, listened to their work and I loved it.” But it wasn’t until one day when she was at a kindergarten conference and noticed the shadow on the floor from the bars on the windows that she was inspired.

“I made a metaphor about how school can become a prison. The poem landed in my head, and it felt WONDERFUL. The muscles or the cells wanted more.”

Then she got lucky, very lucky. She was published in the Paris Review. “I wonder how many persevere if they’re not lucky.”

Powell felt she shouldn’t be writing poetry because it made no money, so she went to work at the Charlotte Observer as book editor, and for 12 years did not write any poetry. “I interviewed authors, to find out how they did it … I was kind of seeking permission to do something other than nonfiction.”

Then she was able to take a sabbatical, and “wrote and wrote and wrote.” Then she got a grant from the NEA. “I got $20,000 or $25,000 and I felt like Scrooge McDuck. I wanted to convert it all into quarters and get in the tub with all that money. I started sending flowers to people. My father was dead by then, but he would have been ecstatic. He might have said ‘I’m sorry for fussing at you for reading fiction.'”

Powell credits a 12th grade vocabulary class for setting a store of words in her brain. “Because we were young and so agreeable, we retained that. I have a storehouse of words I would not have gotten. It’s important to have that bank of words from early reading. When your conscience is writing things you’re not prepared for, you can make more creative moves if you have a bank.”

Most people don’t want criticism of their poetry, she says. “Most people want to express themselves, and that’s fine. … Most people don’t think of being edited or editing themselves or studying other poets.

Powell says, “Poetry is flowery, sentimental, an expression of their deepest feelings and that’s wonderful. It’s separate from the study of the craft of poetry. Poetry is more like chemistry. It is very exact; you have to know when to break a rule and when to follow a rule. It’s about restraint and expression.”

Powell thinks poetry has become freer, more real, less flowery, more accessible. “People put down Billy Collins. He can’t be good because he’s so successful. But there’s another level to his poetry. He’s always talking about something else, usually death.

Sometimes it’s hard to talk about poetry. People ask if it’s true. “A lot of it is factual, but so much is not. I will make things up that should have happened, and sometimes I come to believe that they did happen.”

“Nobody Calls Me Darling” is deeply personal. The emotions are keen and fresh. Don’t miss your chance to hear Powell talk about poetry with Jennifer Hubbard, a novelist and poet, playwright and actress, teacher and student, at the Summer Reading Challenge on June 14, 7 p.m., at Rowan Public Library.