Like father, like son: Charlie Davis and his late dad combined for 80 years with the railroad

Published 12:10 am Monday, July 25, 2016

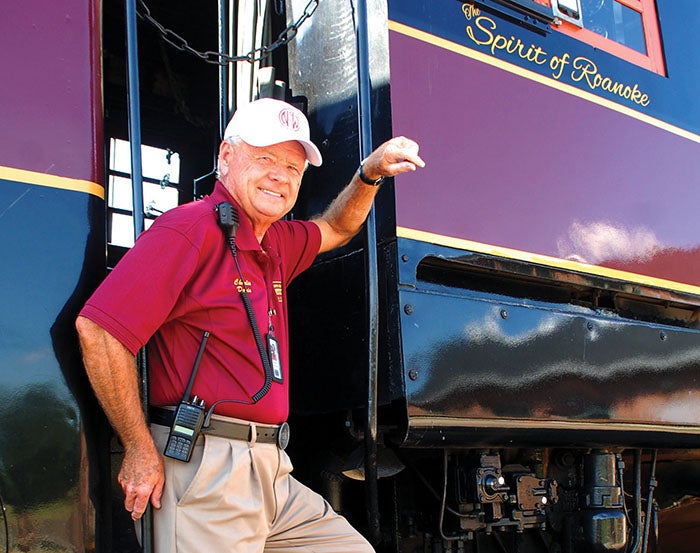

- Mark Wineka/Salisbury Post Charlie Davis Jr. stands on a step to the Class J 611 steam locomotive, which is presently on the grounds of the N.C. Transportation Museum. Davis, a 40-year railroad man, serves as a volunteer at the museum.

SPENCER — Though he still calls a beach house in Little River, S.C., his home, Charlie Davis Jr. has been spending more time lately volunteering at the N.C. Transportation Museum.

On many Tuesdays and Thursdays, he narrates the train ride that takes visitors on a 25-minute journey across the 57-acre site. On these trips, he likes to wear a crisp white ballcap that bears the insignia of Norfolk & Western Railway.

When Davis breaks for lunch, he might pop across the street to Be Bop’s Diner, a place that has some of the best meat loaf he has ever tasted.

No matter how hard he tries, Davis can’t get railroading out of his blood, and he comes by the affliction honestly. His great-grandfather Henry Davis, grandfather Peter Davis, and father Charlie Davis Sr. were all railroaders, as was Charlie Jr. himself.

You could say Davis and his dad, the late Charlie Sr., were the worst offenders. Each of them worked 40 years for the railroad.

LeAnne Johnson, historic sites manager for the N.C. Transportation Museum, plans on putting together a special exhibit in 2017 of photographs, artifacts and the personal stories to go with them from men who worked for the railroad or at the Spencer Shops repair facility, which is home for the transportation museum.

The story of Charlie Davis Sr. likely will be part of that exhibit. Charlie Jr. already has given Johnson some enlarged black-and-white photos of his father from his days as agent at the Walnut Cove Depot for Norfolk & Western.

Charlie Jr. wants this story to be about his dad, but you can’t help but recognize that the junior Davis, who is 70, has led an interesting life himself.

He’s a Vietnam veteran who did a lot of moonlighting during his railroad days. He is a former Stokes County commissioner and mayor of Walnut Cove. He once worked for the U.S. Marshal’s office transporting convicted felons to prison. In fact, he was sitting in federal court in Greensboro the day of the terrorist attacks Sept. 11, 2001.

Charlie Jr. also was a courtroom bailiff for the Stokes County Sheriff’s Office. He helped part-time at a funeral home. Long ago, he even played saxophone and sang for a beach music band — the Covettes — that had gigs in towns such as Martinsville, Danville and Roanoke.

“I’ve just done a lot of stuff,” Davis says. ‘When I die, no one can say I was lazy.”

The story of Charlie H. Davis Sr. is tied closely to Walnut Cove, a small town in Stokes County that before merger was on both the Norfolk & Western rail line between Roanoke, Va., and Winston-Salem and the Southern Railway line between Greensboro and Mount Airy.

Charlie Sr. was the N&W man in Walnut Cove.

He came from a big family in Martinsville, Va. — at least 10 to 12 children combined because of his grandfather’s two marriages, Charlie Jr. says.

Charlie Sr. looked as though he was headed for a career with Western Union. Before he could drive, he was delivering Western Union messages around town on his bicycle. He also went to school in Rome, Ga., to be a telegraph operator.

But in 1937, he changed course and took the job as assistant agent at Norfolk & Western’s Walnut Cove station.

He would later become agent and over 40 years one of the most familiar faces in Walnut Cove. He doubled as the railway express agent, and as such would deliver the goods coming into Walnut Cove by freight train to their final destinations locally.

For example, a shoe store in town received all of its inventory by rail, plus lumber would arrive at the station for the local lumber company.

Charlie Davis Sr. always had a smile on his face. He loved First Baptist Church in Walnut Cove and was on its deacon board for what seemed 100 years, Charlie Jr. says.

Charlie Sr. also served on the Walnut Cove town board.

“Everybody knew Charlie,” his son says.

Charlie Sr. had four boys — Charlie Jr., Dickie and twins Thomas and Tim. They all spent a lot of time at the station with their dad. Charlie Jr. pulls up one of his pant legs to show a scar and mark left by his falling on the heavily cindered tracks at least 60 years ago.

As agent, Charlie Sr. was in constant communication with Roanoke, and he would pass paper orders to engineers coming through Walnut Cove with a device that utilized a long stick with a detachable wooden hoop on top.

The messages to the engineers were clamped onto the hoop. As an engineer rolled by, he hooked an arm inside the hoop to retrieve the order, and he would discard the hoop farther down the track.

Charlie Jr. often would be sent to retrieve the wooden part the engineer had thrown away.

In Charlie Sr.’s day, Norfolk & Western called its route between Roanoke and Winston-Salem The Pumpkin Vine, “because it went like this,” Charlie Jr. says, curling an arm back and forth like a snaking vine.

It later became known as The Pocahontas.

Charlie Jr. remembers riding a train pulled by the Norfolk and Southern’s Class J steam locomotive when he was 6. The Class J 611, normally based in Roanoke, is currently a visitor at the N.C. Transportation Museum.

Another childhood memory: Charlie and his brother Dickie accompanied their father on a train ride from Walnut Cove to San Antonio, Texas. They were going to see Charlie Sr.’s sister there, and in those days a rail employee and his family usually could ride for free by showing a pass.

But a rail employee in Little Rock, Ark., gave the Davis family a hassle, prompting Charlie Jr. and Dickie to start crying, fearing they wouldn’t get back home. The guy finally relented and allowed Davis and his sons to keep going.

A couple of years after Charlie Davis Sr. retired as the Walnut Cove agent, a dentist bought the building and moved it about 5 miles to his farm. The last time Charlie Jr. saw the old depot it was home to hay and goats.

As a teen, Charlie Jr. had a job at a florist shop, and he was lifeguard at Hanging Rock State Park. He was working for the lumber company in Walnut Cove when his father came to him one day and told him Norfolk & Western was hiring clerks in Winston-Salem.

Charlie Jr. applied, secured the job and for the next 40 years was a railroad clerk, assistant chief clerk or yardmaster — all in Winston-Salem. Most of those years he worked from 8 a.m.-5 p.m. and was off on weekends.

As yardmaster toward the end of his career, Davis had a 10 p.m.- 5 a.m. shift, which allowed him to take other jobs during the daylight hours, such as bailiff and inmate transporter for the U.S. Marshal’s Office. He also had to look after his parents when they got sick.

Charlie Davis Sr. died in 2001 at age 92, only four years before Charlie Jr. retired from the railroad. In 2006, Charlie Jr. moved to the beach.

“I’m an old beach music man,” he explains, but he acknowledges the bloom of the beach, especially during vacation season, is wearing off enough that he might consider moving back to North Carolina.

Davis thinks he has lived a pretty charmed life. He has a son, a good railroad pension and a volunteer job that keeps him around trains. His Army experience in Vietnam, Charlie Jr. says, is an example of how someone upstairs has always looked after him.

He was drafted in 1966, and because he was drafted, it meant Norfolk & Western would keep his position available to him when he came back.

At his Army base in Vietnam one day, he was standing in the chow line when a soldier from North Wilkesboro tapped him on the shoulder. He soon learned the fellow was going to recommend him as his replacement to serve as chauffeur for the commanding general of the First Air Cavalry.

Davis was soon driving the general’s brand new Jeep, which had a machine gun on a tripod anchored in the back. “The general I worked for was amazing,” Davis says.

In that job during his stint in Vietnam, Davis was able to transport Gen. William Westmoreland and Hollywood stars Bob Hope and Phyllis Diller, who were part of USO shows. He and his commanding general also would fly by helicopter to Saigon every Friday afternoon for meetings.

Later, before his two-year Army hitch was over, Davis came back to Fort Gordon, Ga., where he was again chauffeur for the commanding general.

And then Davis went home and worked for the railroad. What more could a man want?

Contact Mark Wineka at 704-797-4263, or mark.wineka@salisburypost.com. If you have some railroad artifacts and stories of the railroaders connected with them to share with the N.C. Transportation Museum, contact K. LeAnne Johnson, historic sites manager, at 704-636-2889, extension 230, or kathryn.l.johnson@ncdcr.gov.