Turning ‘Sixty,’ battling with aging

Published 12:00 am Sunday, September 25, 2016

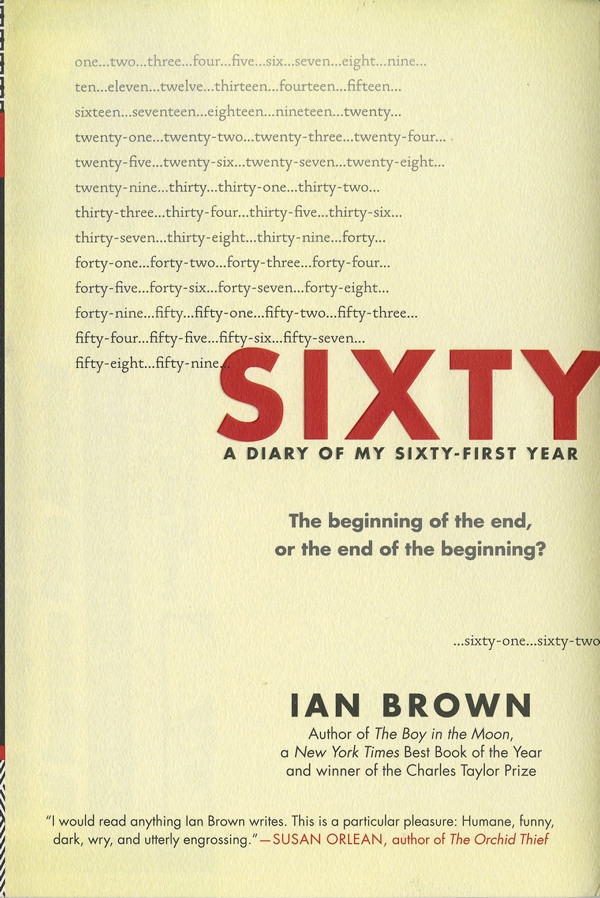

“Sixty: A Diary of My Sixty-First Year,” by Ian Brown. The Experiment. 2016. 320 pp. $24.95.

By Deirdre Parker Smith

deirdre.smith@salisburypost.com

First, let’s get one thing clear – I am not 60.

Birthdays are not so frightening, because they mean I’m still alive. On the other hand, aging is no fun, the little losses, the added burdens.

So when Ian Brown’s memoir “Sixty: A Diary of My Sixty-First Year” showed up, it piqued my curiosity.

At times hilarious and poignant, while also being egotistical and dull in spots, Brown’s diary was entertaining and engaging.

Brown is a literate, well-educated, well-traveled man, a reporter for Canada’s Globe & Mail. There’s no doubt he has admirable writing skills. If he can compose a diary this literate and clever, he is amazing. It’s good to know he edited and perhaps embellished a bit here and there.

Nevertheless, his observations run the gamut to worrying about his sexual functioning to the legacy he might leave, staring at women and wondering if they’d have sex with him and missing his late father, who died at 98.

It’s profound and profane, with enough astute observations and well-crafted turns of phrase to keep me reading, though occasionally I wanted to say, “Ian! That’s enough! Move along.”

Brown did an inordinate amount of research on aging, so some entries read as if he couldn’t bear not to use what he’d learned. Some of it is fascinating, some of it mundane. It’s easy to skip the parts that don’t interest you to get back into the good stuff, and there’s plenty of good stuff. Little scraps of Post-it notes attest to the times when he wrote something that bears repeating.

For example, as he reads, he makes notes in the margins about what is happening in his world. “Why am I making such notes? Because they are as real and as ‘important’ as anything else within the frame of the experience of reading the book.”

He puts many of his experiences in a context that clearly shows how he feels and how universal those feelings are.

Another profound observation: “The difference is that, for an infant, the bigger world, the completing world, the world that you want to become part of, is outside you; but when you are aging, the completing world, the world where you will find peace, is inside you, in part because the outside world doesn’t much want you anymore.”

So he ends with a whine, but his point is hugely important. We do begin to look within after a certain age, because, truly, what we see outside is either frightening, boring or irrelevant to us.

That’s not to say that it’s too late to learn, but that it’s time to process all that we’ve learned, maybe to share it before it’s too late.

“Why do I only understand now, at this late stage, that we never have enough time to say everything we ought to say? That we should stuff the words in at every opportunity, through every crack?”

Not just what we learned, but how much we feel, because the feelings grow as we age, or many of them do. The sense of time following us like a freight train is real.

“How have we managed as a species to progress this far without shattering the illusion that time stretches out before us? It doesn’t. It runs past.”

And in between musings on his friends’ relative fitness, intellectual activity and sex lives, he creates “aha” moments, advice, observations or feelings that hit home.

“If you feel you have to do something perfectly, you will never attempt it. If you know you will fail but figure what the hell, you might just try. Of all the object lessons I should like to pass on to my daughter, this is the important one.”

And later he says, “I wish it was not so hard not to be afraid.”

And this, “I was afraid that trying and failing would be more painful than the failure of never trying at all.”

Incredibly important insight. How many of us fail to try? Think of all the things we could have accomplished. So, try, fail. You’ll survive. It’s not too late. Give up being afraid. It’s easy to say, yes, harder to do, but hear what Brown is saying.

And then there’s his annoying side, his “self-involved intellectualizing.” He makes simple and sometimes insignificant moments seem monumental and rationalizes his intense focus. Here’s where his diary can become aggravating, at the least.

Brown is also concerned with his legacy, which includes his best-selling book about his disabled son, “The Boy in the Moon.” When he and his wife venture out to see the movie of the book, he writes, “… the overall effect of having someone depict your life is that it makes you think your life is over — that it is done, and that the way you come across is beyond your control. I wish I had known this when I was younger; it might have had a freeing effect.”

At least he’s learned that much.

Brown’s diary of his 61st year has plenty of insight, and it’s a fascinating study of a man as he reaches a milestone. Even if he did embellish, the book is still candid. Brown is a good storyteller, a thorough researcher and a real man asking, in his subtitle, “The beginning of the end, or the end of the beginning?”