Michael Bitzer: Supreme Court ready to insert itself into ‘political question’ of redistricting

Published 9:56 pm Wednesday, June 28, 2017

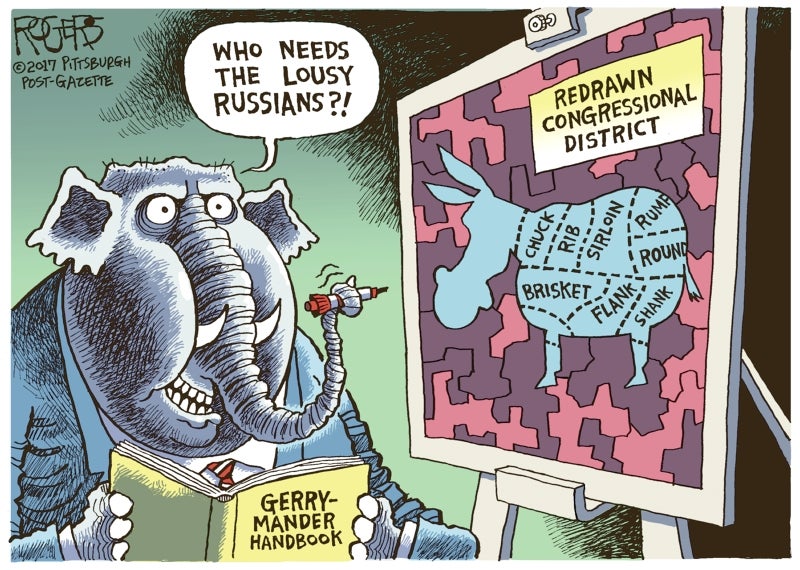

The U.S. Supreme Court has agreed to hear a Wisconsin redistricting case and consider whether partisan gerrymandering is constitutional.

In the past, the courts have deferred on answering whether partisan gerrymandering is constitutional or not for the simple fact that it inserts the judiciary into a “political question.”

In 2004, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a redistricting effort, drawn by Republicans, in Pennsylvania against the claim that excessive partisan gerrymandering occurred. In the majority’s opinion, Justice Antonin Scalia noted that partisan gerrymandering is as old as colonial America, and that ultimately, it is not for the courts to insert themselves into the political actions of legislative redistricting.

However, one justice, who joined the majority’s opinion, wrote that while there was no judicial standard by which to judge when a district was politically manipulated through gerrymandering, he would “not foreclose all possibility of judicial relief if some limited and precise rationale were found” to adjudicate the issue of partisan gerrymandering.

In his concurrence, Justice Anthony Kennedy laid out what he saw as the two obstacles to tackling partisan gerrymandering by the courts: first, that there are no “comprehensive and neutral principles for drawing electoral boundaries,” and second, there are “rules to limit and confine” when the courts should engage in reviewing redistricting claims.

The Wisconsin redistricting case may have some of the answers to Justice Kennedy’s concerns about inserting the courts into reviewing partisan gerrymandering. Much has already been analyzed about the Wisconsin cases that will be reviewed in next year’s term of the Supreme Court, but the Old North State is certainly one that will be watching the developments.

At the heart of redistricting controversies is the issue of when one party “packs” or “cracks” voters. By placing an over abundance of voters who cast ballots for one party into a district (thus “packing” partisan loyalists), it frees up surrounding districts to favor the other party. Conversely, by splitting those same partisan voters into multiple districts, they are said to be “cracked” into districts to avoid being able to elect one of their own.

An example of “packing” could be seen in the recent North Carolina congressional districts in 2016. With new congressional district maps drawn by Republicans in the North Carolina General Assembly, the vote totals for all Republican congressional candidates came to 53 percent of the statewide vote; however, they won 10 out of the 13 seats, or 77 percent. The Republican congressional district with the largest margin of victory was in the Third District, with GOP Walter Jones winning 67 percent of the vote. The “narrowest” GOP winner was in the 13th District, with first-time Republican Ted Budd receiving 56 percent — one point above what most political scientists would consider a “competitive” range of 45 to 55 percent.

Conversely, the three congressional Democrats won with over two-thirds of the votes in their respective districts.

In 2016’s N.C. General Assembly elections, Republicans won 52.4 percent of the statewide vote in the state House elections, but secured 61.7 percent of the seats; in the state Senate, Republicans won 55 percent of the statewide vote cast, but laid claim to 70 percent of the upper chamber’s seats.

This pattern — of one party winning a greater percentage of the districts than their statewide vote — is a similar claim to the issue of the challenged Wisconsin districts as well. And ultimately, it will be Justice Kennedy who determines if the Wisconsin case brings a satisfactory way of having the courts intercede in this most political of activities in the United States.

Dr. Michael Bitzer, provost and professor of politics at Catawba College, is from his WFAE radio blog, The Party Line.