College Football: Bill Griffin gets the Hall of Fame call

Published 11:34 pm Friday, September 1, 2017

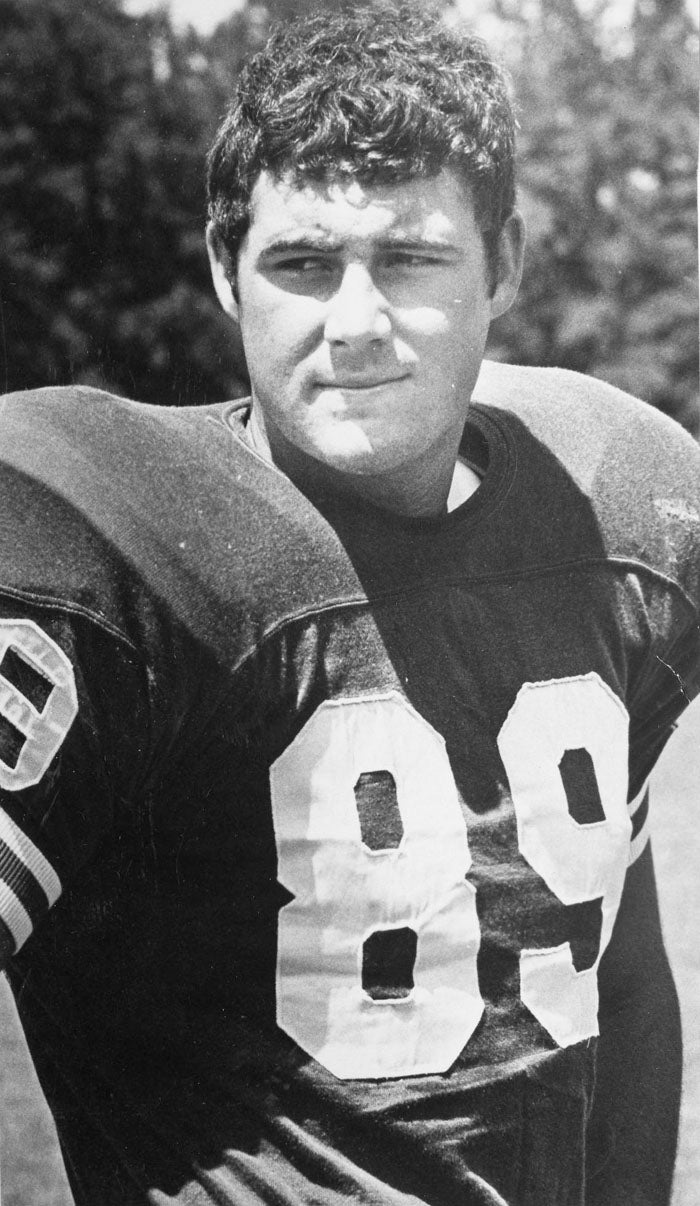

- Post file photo ... Bill Griffin, during his Catawba football days in the late 1960s.

By Mike London

mike.london@salisburypost.com

On a farm in Fort Wayne, Indiana, Bill Griffin, once a dominating defensive tackle, received a call from the Catawba College Sports Hall of Fame.

It was a call he’d stopped anticipating, stopped hoping for, so it was an emotional moment. Griffin, 69, will be inducted on Nov. 10, along with five relative youngsters — Mike Delabar, Adrian Gantt Whitley, Danyel Locklear Jolicouer and Luke Samples. None of those five had been born when Griffin was crushing Carolinas Conference ballcarriers in the late 1960s.

Catawba legends that Griffin went into battle with at Shuford Stadium — Ike Hill, Mike Dickens, Drew Buie, David Taylor, Ed Koontz and Greg Singleton — have been enshrined for at least two decades.

“I’m grateful, honored and humbled to be chosen for the Hall of Fame,” Griffin said. “I’d gotten a call from Catawba a a few years back, wanting some information on me, but when nothing happened then, I thought it probably never would.”

Griffin never played in an NFL regular season game, but he came as close to the being in the NFL as it’s possible to get without actually being there — and with four different teams. He’s got stories. He was drafted by the Dallas Cowboys. There’s no doubt he was a great player.

Griffin grew up in Edenton, in eastern North Carolina. The big rival was Elizabeth City, and the echoes of the 14-all tie in 1964 between Griffin’s Edenton Holmes Aces, ranked No. 1 in 2A, and Elizabeth City, ranked No. 1 in 3A, are still heard in that area. Griffin’s ball-carrying teammate was Wes Chesson, who became a Hall of Famer at Duke and an NFL receiver. Griffin was coached by Jerry McGee, who had helped Duke beat Arkansas in the 1961 Cotton Bowl. Griffin’s team won the NCHSAA’s East Region in 2A in 1964 and 1965, and he was chosen to play in the Shrine Bowl, the top all-star game in the Carolinas.

In a 31-27 loss to the South Carolinas stars, Griffin played alongside such players as Thomasville’s Ron Carpenter and Charlie Bowers and Asheboro’s Darrell Moody. Those three headed to Raleigh to play for N.C. State. The Wolfpack also wanted Griffin, who was 6-foot-5, 235 pounds and athletic. He was a fierce high school basketball player and a record-setting shot putter in track and field.

“I was pretty heavily recruited, but when I went to visit those schools like N.C. State and Carolina, they didn’t feel right,” Griffin said. “Those schools were too big for a country boy from Edenton.”

It was getting late in the recruiting process when Griffin came to Salisbury, “on a whim,” to visit Catawba.

Catawba did feel right. Head coach Harvey Stratton was obviously interested — 6-foot-5 guys who could run didn’t walk into his office every day — but he said he was out of scholarships.

“What if I earn a starting position a freshman?” Griffin said.

“Then we’ll see what we can do,” Stratton replied.

Griffin had played some nose guard in the Shrine Bowl, and that’s the position where he earned his spurs as a Catawba freshman. Then he was on scholarship.

“I played with some great players, guys like Hill, Taylor, Buie,” Griffin said. “Watching Buie run track is something I’ll never forget. It didn’t look like he was even running hard, but he was flying.”

Despite a locker room full of fine players in that area, Catawba experienced modest team success.

“When I was a senior in 1970, that’s when we had the team that was going to kick some butt,” Griffin said. “But first game of the season Taylor goes down at Mars Hill with a season-ending knee injury.”

Taylor was playing defense when he went down. Taylor recovered and would play in the NFL on the offensive line for the Baltimore Colts from 1973-79.

Griffin played a lot of different positions for Catawba on both sides of the ball, but he believes defensive end was his best position. He recovered a school-record three fumbles in the 1970 game when Catawba rolled against Newberry, 41-21, and he was player of the week after a 45-16 pasting of Emory & Henry. Catawba started the 1970 season, 4-0, but things went south after a loss to Appalachian State. The Indians finished 5-5.

Griffin’s star was still bright. Gil Brandt, the vice president of player personnel for the Cowboys, had scouted Griffin and liked him.

When the 1971 draft was held, the Cowboys took Griffin, who had gotten his weight up to 250 pounds. He was picked in the seventh round as an offensive lineman.

“An exciting time,” Griffin said. “Gil Brandt called me the day of the draft, told me the Cowboys were going to take me.”

But that was a tough Dallas team to make. The Cowboys had been NFC champions in 1970 before losing to the Colts in Super Bowl V.

“I got to be on the field with guys I’d watched on TV — Mike Ditka, Dan Reeves — and I was briefly coached by Tom Landry,” Griffin said. “There were 40-man rosters then, plus “Taxi Squads,” a handful of guys who were on reserve in case of injury. Dallas had a great starting offensive line. The backup guard spot was going to come down to me (and fellow rookie) Rodney Wallace.”

Dallas traveled to Baltimore for the final preseason game, a grudge match to avenge the Super Bowl defeat.

“Then I get sick, and the team is going to Baltimore, and I have to stay behind,” Griffin said. “I’m watching it on TV and the Cowboys are kicking the Colts around, and Rodney Wallace, my competition, is having the game of his life. And I know Rodney is going to be the backup guard.”

Griffin was cut. He went home to Boca Raton, Fla. He’d been there a day when the Miami Dolphins called. Coach Don Shula was on the other end of the line. Landry had recommended Griffin. Griffin was practicing with the Dolphins not long after that.

He was placed on the Dolphins’ Taxi Squad. He traveled to the all games, ready to be activated at a moment’s notice. He remembers the trip to Buffalo when his ex-Catawba teammate Hill introduced him to Bills running back O.J. Simpson. Simpson made an amazing touchdown run that day, but the Dolphins won the game.

The Cowboys beat the Dolphins in the Super Bowl at the end of that season in Tulane Stadium in New Orleans. Griffin had spent some time with both teams.

The next year, the legendary 1972 Dolphins would go undefeated, but Griffin wasn’t around to be part of that.

“I remember Coach Shula calling me in and telling me most of his offensive linemen were All-Pro and the rest were all-conference,” Griffin said. “He said I’d have a much better chance to play for the (struggling) New England Patriots. He told me it was up to me, but he could make the trade if I wanted it. I wanted the opportunity to play, so the Dolphins made the deal. I was headed to Foxboro.”

Griffin was traded straight-up for linebacker Steve Kiner, the former Tennessee All-American who had started for the Patriots in 1971.

The Patriots were in turmoil with general manager Upton Bell and coach John Mazur clashing over personnel moves. Bell had made the deal for Griffin. Mazur wasn’t interested in playing him. Both Bell and Mazur would be fired as the 1972 season turned ugly for the Patriots.

“I got caught up in some politics in New England, and it was a tough situation for a 22-year-old kid who just wanted a chance to play,” Griffin said. “When the Patriots had to get down to 44 men, they cut me.”

Bell felt remorse for Griffin’s plight, apologized, and made some phone calls. One was to Pittsburgh Steelers owner Art Rooney. It was the last week of preseason camp, but Rooney said the Steelers, who were in the early stages of becoming the NFL’s next great team, would be happy to give Griffin a look.

“I was upset, full of adrenaline after seeing everything I’d worked for going down to nothing,” Griffin said. “I knew I faced long odds, but then I went to the Steelers’ camp and played as well as I ever have.”

He was asked to stay after practice one day to work on his pass-blocking against the starters. The veteran lineman hung around to watch, certain that Joe Greene and L.C. Greenwood would knock the kid on his butt.

“But I blocked them,” Griffin said. “At the end of that practice, some of the veterans applauded. The guys told me I’d made the team, for sure, that it was time for me to start looking for an apartment.”

But he didn’t make the Steelers. Coach Chuck Noll cut him.

There was one last NFL phone call. It was from Shula. Wayne Moore, a Dolphins lineman, had hurt a knee. Shula wanted to know if Griffin could report to the team if Moore’s knee didn’t come around.

“I told him I would,” Griffin said. “But the knee must have come around. He never called.”

That was it for football.

Years in the farming and fishing industries followed.

A back injury led to Griffin looking for ways use his brains rather than his brawn. An opportunity with American Express led to a leap of faith and relocation to Lima, Ohio.

After five years with American Express, Griffin built his own financial planning business. He was successful and retired three years ago.

Griffin was one good break away from playing for the Cowboys, Dolphins or Steelers, probably the three most talented teams of his era.

But now he’s a Hall of Famer. There are few regrets.

“The biggest thing I’ve learned is that everything my Catawba coaches tried to tell me years ago, well, they were right,” Griffin said. “Looking back, I was lucky to have coaches like that in my life.”