Ferrel Guillory: Schools seeking ‘restart’ surge after last round of testing

Published 5:37 pm Monday, September 18, 2017

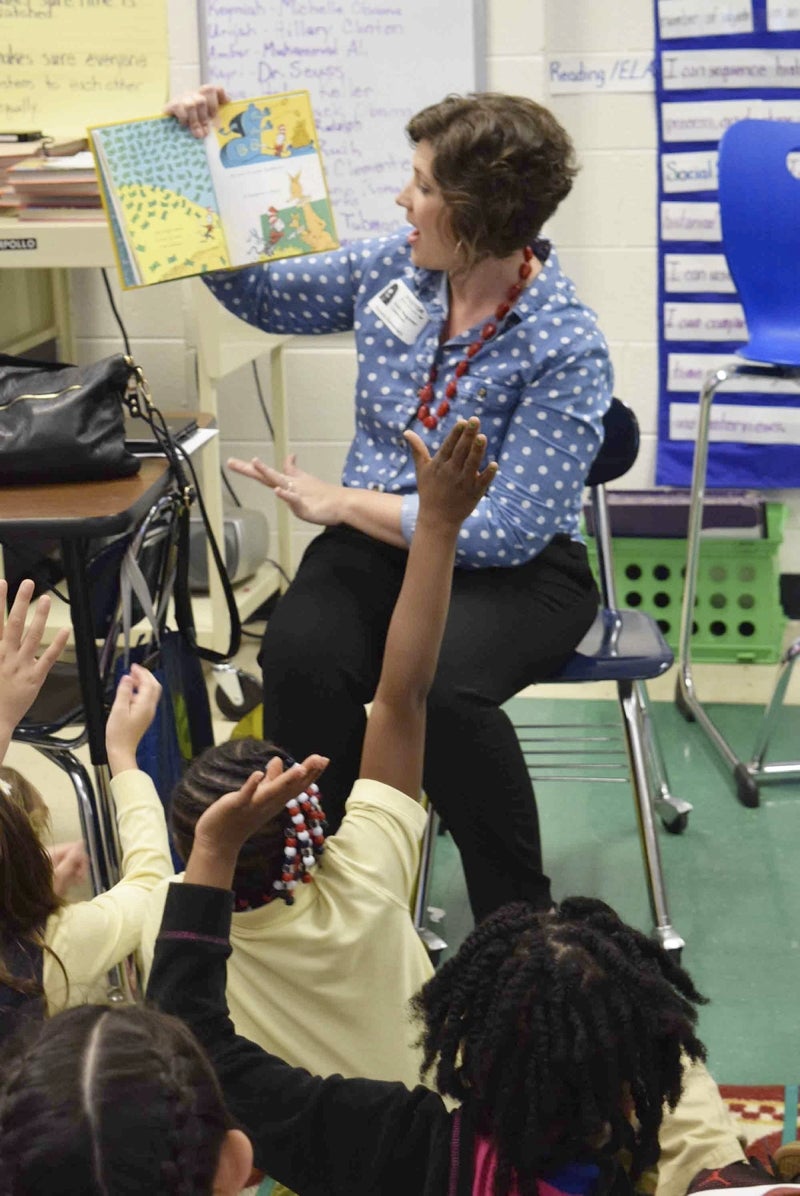

- Holly Wagoner, a volunteer with Read Across Rowan and Cabarrus Counties, reads to a second-grade class at Koontz Elementary School in honor of Dr. Seuss's 113th birthday. Rebecca Rider/Salisbury Post

The streams of data released recently by state education authorities flowed out in familiar patterns: Another modest increase in the high school graduation rate, a slight uptick in the schools with A or B grades, a slight decline in schools graded D or F, but a rise in the number of schools defined as low-performing.

Now here is a statistic, not released along with the other data, that points to an emerging dynamic in addressing low-performing schools, most of them defined by a heavy enrollment of students from low-income families: The number of “restart’’ schools has risen from seven in mid-2016 to 109 today.

Under a 2010 state law, any public school deemed low-performing in two out of three years can qualify to become a restart school. Once designated a restart school, a school is exempted from many state regulations and operates much akin to a charter school.

School boards, superintendents and principals from a geographically diverse array of counties have applied to and received approval from the State Board of Education to shift low-performing traditional public schools into restart mode — a dozen or so schools in Wake, Rowan-Salisbury, Charlotte-Mecklenburg, and Durham; several in Halifax, Warren, Edgecombe, Gaston, and others.

This movement has received less attention than the creation of the Innovation School District, established by the General Assembly and designed to give management of low-performing schools to private charter-school operators. The Innovation District plans to adopt two schools this year and three the next.

Unlike charter schools and Innovation District schools, restart schools remain governed under their local school boards. Their teachers and staffs remain district employees. But in both educational practices and day-to-day operations, restart schools would resemble charter schools.

Restart schools have flexibility in setting teacher salaries and roles, and in shifting funding to support educational priorities. These schools can change student assessments and teacher evaluation. Half of their faculty can consist of lateral-entry or specific-knowledge teachers not licensed under traditional certification. Restart schools can extend the school day or school year to give their students more learning time.

Even as restart schools get flexibility to exercise fiscal nimbleness and educational creativity, they still need adequate funding, as do all of the more than 2,500 schools supported with state appropriations in North Carolina. The structure of principal salaries needs redesigning to enhance the state’s ability to attract strong school leaders, and teacher pay should be aligned with the compensation of similarly situated professionals.

Among the opportunities that come with the rise of restart schools is the potential of learning what works and what doesn’t, and sharing lessons among the restart schools and between restart schools and traditional public schools. Already, some superintendents are consulting each other in the planning and early implementation stages. After all, they share a common challenge: lifting the educational achievement of young people who bear burdens resulting from poverty and near-poverty.

Combined, the Innovation schools and the restart schools address barely one-fifth of the state’s distressed schools. North Carolina had 468 recurring low-performing schools in the 2016-17 school year, up from 415 the previous year.

You can not say, therefore, that the state has launched an all-out assault yet on low-performing schools — an initiative of such intensity as to lift overall academic achievement substantially. Still, you can say that the surge in restart schools suggests an adaptability in the public school system to the pressures and opportunities of this moment of flux in educational policy.

Across North Carolina, the population profile of school-age children is that half are whites, about a fourth are blacks, and a fourth Latinos and Asians — they are the multi-ethnic future of the state civic life and its workforce.

State data show that in nearly 1,500 schools, more than 50 percent of the students come from households living in poverty. The importance of restart schools, therefore, does not rest simply in bureaucratic shifts in how schools operate but rather in their potential for figuring out how to educate and graduate thousands more high-performing young Tar Heels.

Ferrel Guillory is the director of the Program on Public Life, professor of the practice at the UNC School of Media and Journalism, and the vice chairman of EducationNC.