D.G. Martin: Make a resolution to read a black history book

Published 12:00 am Thursday, January 25, 2018

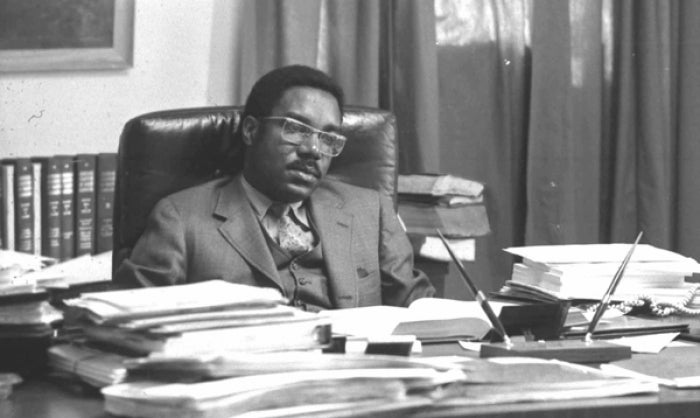

- Julius Chambers

By D.G. Martin

Here is a New Year’s resolution you should have made: During the upcoming Black History Month I will read at least one book that helps me better understand the challenges African-American people have faced and are facing.

It is not too late. February is almost here. Assuming you accept this challenge, let me suggest you consider several North Carolina-related books I have read recently. I will tell you a little about each one, hoping to give you reasons to make a choice. Whichever one you select could open doors to a greater understanding of the black experience and a richer appreciation of what it is like to be black in North Carolina and our region.

The late attorney and university chancellor Julius Chambers is a North Carolina hero. Although he would deny the comparison, he was our Martin Luther King. In the courtrooms, he held North Carolina’s feet to the fire and moved away mountains of unfair laws and overturned government actions that discriminated against blacks. All the details of Chambers’ battles are laid out in “Julius Chambers: A Life in the Legal Struggle for Civil Rights” by Richard A. Rosen and Joseph Mosnier.

Their account of Chambers’ experiences in law school where he was editor of the law review, his courageous battles in the courtroom, and the ever-present dangers that followed wherever he went are at the crux of his contributions. But most inspiring to me is the account of his growing up in the post-Depression ravages of rural Montgomery County. When a white customer cheated Chambers’ car mechanic father and no lawyer would represent him, Chambers’ family lost the resources to pay for a good high school education.

The opening words of Kenneth Janken’s book, “The Wilmington Ten: Violence, Injustice, and the Rise of Black Politics in the 1970s,” let us know why this book is important: “The case of the Wilmington Ten amounts to one of the most egregious instances of injustice and political repression from the post–World War II black freedom struggle. It took legions of people working over the course of the 1970s to right the wrong.”

The story begins in 1971 when the treatment of black students in Wilmington’s newly integrated high schools prompted a boycott and demonstrations, followed by violent confrontations and burning of small businesses. Some of the boycott and demonstration leaders were arrested and charged with arson.

The prosecutor used perjured testimony to secure a conviction of 10 defendants known as the Wilmington Ten. The battle to overturn the convictions took more than 40 years. Those of us who oppose riotous demonstrations are forced to confront the question of what other alternatives were available.

In “The Blood of Emmett Till,” Duke professor Timothy Tyson retells and adds to the story of the 1955 kidnapping and brutal killing of Till, a 14-year-old black youth from Chicago visiting relatives in Mississippi.

Tyson reviews the indignities suffered by blacks across the South: Never look a white person in the eye. Never say or do anything that could be viewed as disrespectful. Do not attempt to register to vote. Violating these and other unwritten rules in our regions could lead to loss of employment, burnings, midnight gunshots into your house, brutal beatings, and death.

Also on the list of possible Black History Month books is Stephanie Powell Watts’s novel “No One Is Coming to Save Us,” which was discussed recently in this column. Watts’s fictional look into a modern day African-American family shows that although the horrors faced by Chambers, the Wilmington Ten, and Emmett Till are mostly things of a past era, the struggle for real equality is far from over.

D.G. Martin hosts “North Carolina Bookwatch,” which airs Sundays at 11 a.m. and Thursdays at 5 p.m. on UNC-TV. Today, guest Karen Cox, author of “Goat Castle,” talks with guest host Malinda Maynor Lowery.