Is love the magic that saves us?

Published 12:00 am Sunday, March 11, 2018

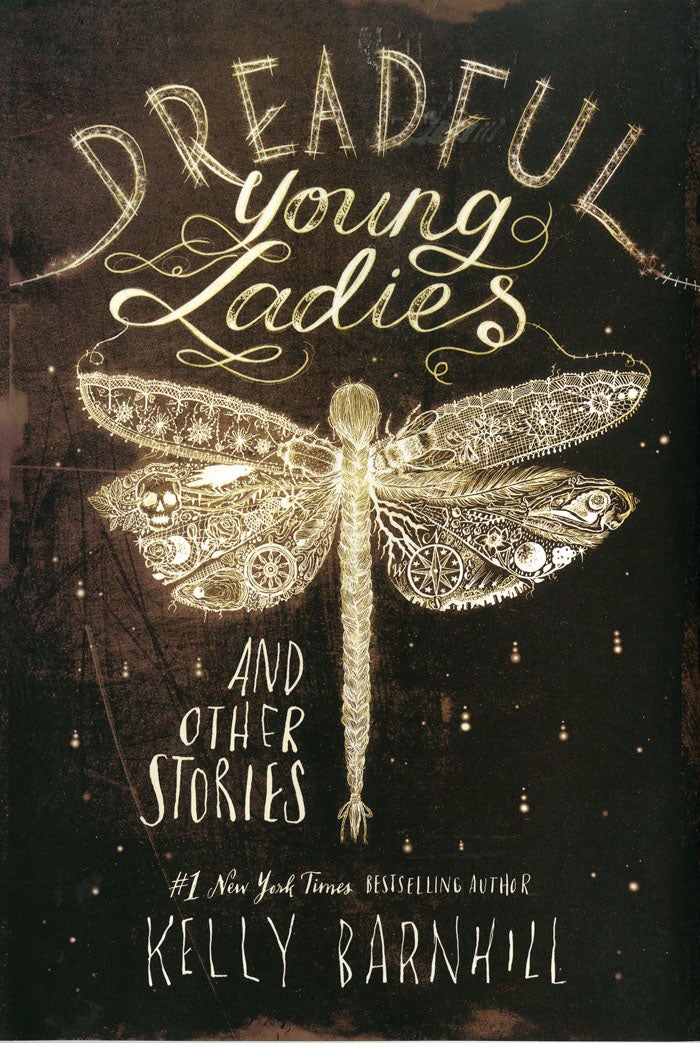

“Dreadful Young Ladies and Other Stories,” by Kelly Barnhill. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. 2018. 288 pp.

By Deirdre Parker Smith

deirdre.smith@salisburypost.com

Kelly Barnhill’s “Dreadful Young Ladies and Other Stories” is fantastic.

Fantastic because it’s full of fantasy. And her fantasy speaks of love, kindness, forgiveness, hope, all things that need reinforcing in our world.

Included in the book is a novella, “The Unlicensed Magician,” which is saturated with incredible magic. The theme is simple — love. Make other people happy. Be generous. Love your enemies. Embrace your fate.

The first story, “Mrs. Sorenson and the Sasquatch” is immediately endearing. Mrs. Sorenson, a recent widow, changes her life, beginning with the funeral. Father Laurence is astonished to see rabbits peeking out from under the front pew, a large buck regally waiting at the front door.

Their small town is a popular location for the Sasquatch, his furry figure seen walking through the forest. The priest remembers seeing him when he was a child.

It doesn’t take long for the eager suitors to the widow Sorenson to be disappointed. There the Sasquatch is in church with her, wearing nothing but Mr. Sorenson’s old hat. The church ladies — women who point fingers and scold and complain — are outraged. Accompanying the couple are a one-eyed hedgehog, a tiny cat, a raccoon, a three-legged dog, and an infant cougar, asleep in her lap.

As the processional begins, “The organist sat under a pile of cats and made a valiant effort to pluck out the notes of the hymn. The congregation — both human and animal — opened their throats and began to sing, each in their own language, their own rhythm, their own time.”

“… It was, people remarked later, the prettiest Mass they’d ever heard.”

Hand in hand, Mrs. Sorenson and her Sasquatch leave the church, walking into the bog. “The world was birdsong and quaking mud and humming insects. … They did not come back.”

Barnhill writes of heartbreaking love in “Open the Door and the Light Pours Through,” in epistolary style, labeled “What he wrote” and “What he did not.” Think of how often we fool ourselves, and think we are fooling others.

Barnhill’s imagery and construction are lyrical, magical, almost like poetry. It’s easy to find the rhythm of the stories, to enter the impossible, unusual world she creates each time. It’s a world of color and wind, of tactile pleasures and ethereal dreams.

The stories are from a different time, a different place or a distant place. Barnhill imagines lush settings with brilliant details, bright flowers, glowing butterflies, beautiful hens that lay stunning eggs.

Barnhill has a fascination for taxidermy, an art, she says, that requires precision and feeling. In “The Taxidermist’s Other Wife,” she introduces a man who has ultimate power. “The Taxidermist is the mayor, and has been for the last fifteen years. We did not vote for him. We’ve never met anyone who has. And yet he has won, term after term.”

His second wife is absolutely perfect, like a porcelain doll. The Taxidermist shuts down the newspaper, closes the hardware store, the seed store, the gas station, and finally, the school. What happens is bizarre, but the Taxidermist does it for love.

In “Elegy to Gabrielle — Patron Saint of Healers, Whores & Righteous Thieves,” Barnhill treats us to a pirate story, a legend. It may or may not be true, as it’s told by a man long dead, a man who loved the pirate. The child Gabrielle is a healer — her touch can make barren gardens fertile and heal the sick. Her mother and her secret father do all they can to protect her from those who would steal her magic.

She brings fish back to life, resurrects a huge, scruffy dog, and becomes the object of the Governor’s attention. She frees slaves from chains at sales. She scuttles ships.

When the Governor has had enough, and knows who to blame, ”Soldiers came for Gabrielle. Marguerite saw them come. She stood on the roof of her house and raised her hands to the growing clouds. The soldiers looked up and saw that the sky rained flower petals. The petals came down in thick torrents, blinding all who were outdoors.” What will become of this magical child who escapes to the sea? Barnhill creates a conclusion full of wings, color and air.

The wicked stepmother story is remade in “Notes on the Untimely Death of Ronia Drake,” with more magic — to vanquish anger, jealousy and selfishness.

The most fantastical, fascinating part of this book is the novella, “The Unlicensed Magician.”

Barnhill lets her imaginative power soar in a whirl of color and song, of love, love, love. Creating a Big Brother figure — in this case called the Minister, a man desperately grasping for his own weird utopia — Barnhill tells a heartbreaking story. Magical babies are born every 25 years when the Boro comet appears. The minister is greedy for those magical children to fulfill his dream of touching the sky. He uses them up, sucking out their magic like a leech.

And it’s all because one girl is willing to give all. The Minister tells her, “I will love you to bits.”

“As I love you, the junk man’s daughter thinks. As I love you and love you and love you. And she does. She loves him so much. As she loves everyone. It is dangerous, this love, and she can’t control it. It is ever so much bigger than she, and growing by the day.”

A tsunami of love from the children finally stops the Minister — a lonely old man — and transforms the land once beset by fear and secrecy into a wonderland bursting with love and magic. The flood opens new land, creates new beings, brings hope.

These stories, and particularly the novella, rise above anything solid and sure. They contain a high sense of morality, a clear message that love is the highest magic of all.