You’ll find yourself enchanted by ‘Circe’

Published 12:00 am Sunday, July 1, 2018

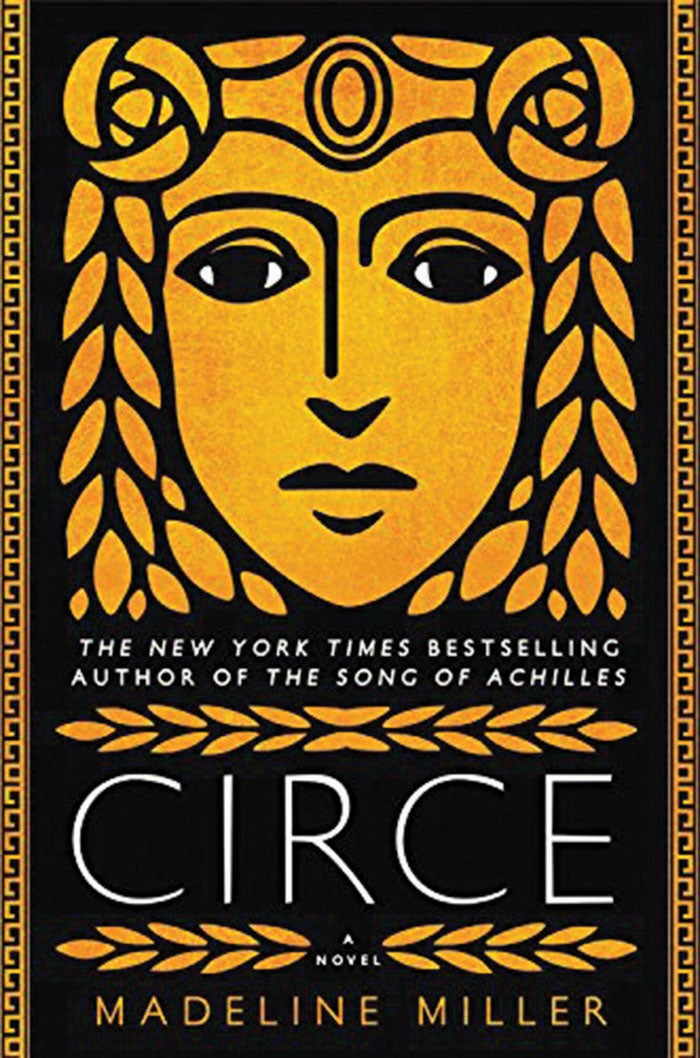

“Circe” by Madeline Miller. Lee Boudreaux Books, Little, Brown. 2018. 400 pp.

By Deirdre Parker Smith

deirdre.smith@salisburypost.com

Maybe you learned some mythology in history class or while taking Latin.

Circe is a name that might sound familiar, but that’s about it.

Along comes Madeline Miller and her new novel, “Circe,” and all is revealed — at least in Miller’s retelling.

Circe is mentioned in the “Odyssey,” when Odysseus lands on the shore of the island she has been exiled to, Aiaia. The novel tells of men who landed on her island before, brutalizing her and stealing from her, though she is the daughter of the Titan Helios and a nymph.

She has become a witch, relying on pharmaka to create spells and transform things. With troublesome warriors and weary sailors, a draught in their wine turns them men into pigs when she speaks the right words.

In the novel, she falls in love with bright and bold Odysseus. In mythology, she enchants him and forces him to stay with her. Miller empowers her Circe with a strong will, some common sense and loneliness.

She’s been exiled by Zeus for her witchcraft — a practice the gods fear. Her island, populated by wild animals she has tamed and groups of nymphs and dryads who have disobeyed their fathers, provides beautiful flowers, magical herbs, rich land and abundant trees and fresh waters. She wants for nothing but attention.

She has come to like mortals, ever since she fell in love with Glaucos, who she later turns into a sea creature. She needs a little TLC, and to show off her skills as a witch.

Miller begins the story when Circe is wandering the obsidian halls of her father’s palace. Helios is sun and has other children, including dreaded Pasiphaë, who will later mate with a sacred bull to produce the fearful Minotaur, and baleful Perses. Their brother Aeëtes is also a witch, a cruel one with a chariot pulled by dragons.

Young Circe meets Prometheus as he is hauled to her father’s house for a lashing and to learn his punishment for giving mortals fire. She brings him a drink, and speaks to him in secret — a crime even Zeus would not stand for, if he knew.

Miller uses the names of the Titans, the gods, the nymphs and kings of the ancient world as easily as we would describe the people in our neighborhood.

She brings Circe to a life of cleverness and longing. She paints her bright eyes and her glowing appearance. Circe has always been described with braided hair, a nod, perhaps, to eastern goddesses. Miller explains Circe braids her hair so it doesn’t get tangled in her search for herbs and barks.

Circe has encounters with Hermes, with Daedalus, whom she loves, with Medea, Ariadne, King Minos. Oceanus is her grandfather, keeper of the river that circles the world.

If you study her family tree and the references to her from Homer’s “Odyssey, Hesiod and Aeschylus, it’s a fascinating, many branched tree with leaves of legends abounding. Circe is pictured on ancient vases and other artwork, and she’s been the subject of modern era artists, as well.

The only child Miller mentions is Telegonus, of whom Odysseus is the father. Therein lies a pending tragedy. Mythology gives her several other children.

Throughout the novel, Miller paints Circe as a misunderstood woman. She regrets creating the monster Scylla, one of the many plot threads in the story. She feels she must rectify her terrifying error.

Mythology paints her as somewhat cruel, unthinking in her magic and overbearing towards others.

Miller captures the woman of power who has lost everything in her exile, and seeks constantly to use her powers to her advantage. If that means turning unruly guests to pigs, so be it.

Circe has no family, no friends, just the animal companions. She uses spells to protect herself, not just as an amusement. When she finds the one thing that matters, she becomes like the lions who accompany her — fiercely protective — and no human could blame her for that.

Miller’s Circe is a fascinating woman, her powers important, but not defining. She can be duped because she is hopeful and hungry for connection.

She knows what the gods are like, capricious children who love nothing more than to laugh at the suffering of others, humans, yes, but fellow gods, especially.

The gods, she explains, favor certain mortals or immortals, but they don’t feel real love or sadness. They are so ancient, it’s all just a game.

When Circe has lived for generations, she realizes what she truly wants. Will she be able to achieve that?

Circe’s world is one of incredible stories, great pains, great danger, death, destruction, whims and moods. She is susceptible to those moods and whims, as well, but in Miller’s hands, she doesn’t take the sick joy from it that her relatives might.

“Circe” is a good read for people who enjoyed mythology, and for people who enjoy fabulous stories and a sense of danger.

Is it something a book club could discuss, certainly. There are issues that still exist today: relationships between parents and children, between siblings, between jealous warriors. Did Odysseus have a tragic flaw? Did Daedalus? Are we victims of fate or destiny, or can we steer our own course?

Miller is also the author of “The Song of Achilles,” and teaches Greek, Latin and the classics. It’s obvious she is caught up in that complex world of mythology.

Margaret George said of “Circe,” “This is as close as you will ever come to entering the world of mythology as a participant.”