Fred Rogers, ‘The Good Neighbor’

Published 12:00 am Sunday, October 14, 2018

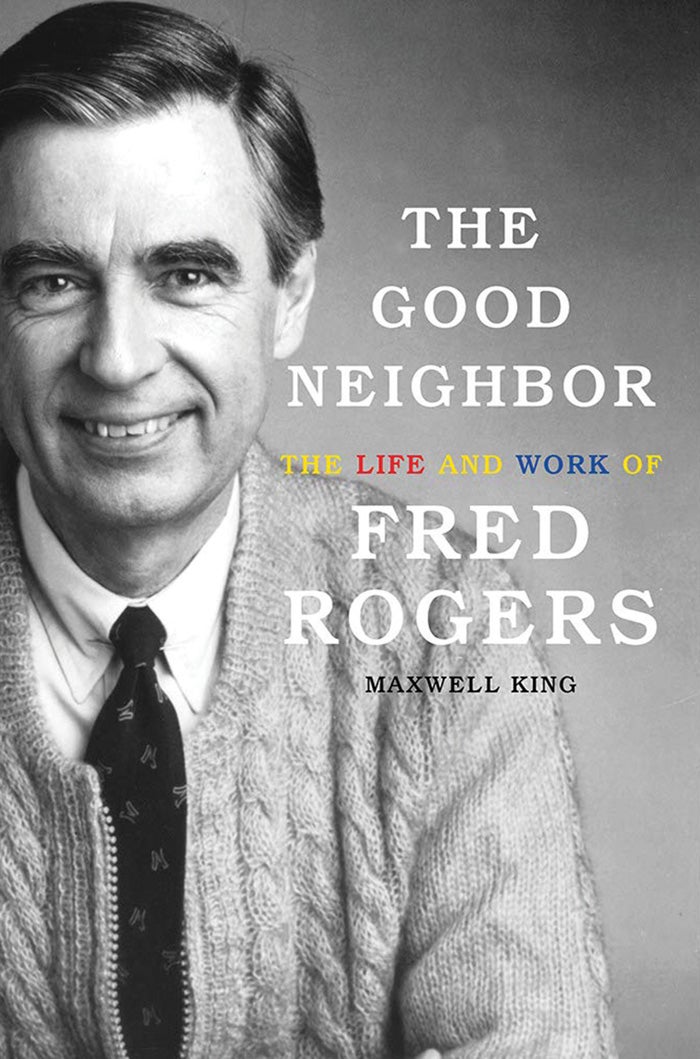

“The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers,” by Maxwell King. Abrams. 2018. 416 pp. Indexed.

It’s almost everything you wanted to know about Fred Rogers. And there’s nothing to be afraid to ask. Yes, Fred Rogers was that good. Yes, he was sincere, and yes, he loved and esteemed children and really knew how to teach them what they needed to know at the right times.

I was too old for Fred Rogers, but his influence is undeniable. He is the definition of kinder and gentler. He spoke more easily to children than adults, but he absorbed tremendous amounts of knowledge that made him an amazing person.

Fred Rogers, according to “The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers,” by Maxwell King, was no Mr. Milquetoast. He was smart, well educated, a deep thinker, a man open to all races, genders, feelings, abilities and disabilities. When someone compared him to Jesus, he became upset, but he certainly embodied the true spirit of Christianity. He suffered the little ones to come to him. He forgave. He taught. He accepted.

This biography is a big one, and the reader will learn all about Fred’s wealthy but circumspect parents, his overprotective mother and his very generous father.

Readers will suffer along with Fred at Dartmouth, where he didn’t fit in, but rejoice when he gets to Rollins in Florida, where his musical talent bloomed and he met his future wife, Joanne, along with many lifelong friends.

The book goes into great detail about how Rogers came to television, and how what he wanted to do and what commercial networks wanted to do were polar opposites.

Rogers not only had firm ideas, he had a firm Presbyterian faith, and studied in seminary, though he realized he could never lead a congregation.

What made him different was his concern that children were being bombarded by loud, sometimes violent images on the new medium of television. Networks weren’t sure what they were doing at the dawn of the TV era. They showed old movies, mostly Westerns, and their children’s programs ran to big, loud clowns, people hitting each other — as in Punch and Judy — and jokes that were much more mature than their audience could grasp.

Through all this, Fred kept searching for the right place to do what he believed to be right. He studied with one of the most well known child development experts of the time, Dr. Margaret McFarland, who had studied with none other than Dr. Benjamin Spock and Dr. Berry Brazelton, the recognized experts on child behavior at the time.

For Rogers, learning about the development of a child’s brain was almost a religion unto itself. Very young children, 2-3 years old, can’t even deal with flashy, frenetic images. They have to have a slower pace, though not as slow or wordless as the bizarre “Teletubbies” of another generation.

While Sesame Street was growing up from its puppet show beginning and adding characters and situations, Rogers wanted to keep things simple, and he did not want to profit from merchandise tied into the show.

So, for commercial TV, he was almost an anathema. Rogers had built his own puppets, he wrote all his shows, he handpicked the cast. He wrote all the music for the shows, and at the beginning, he was never seen on camera. Shows dealt with just one topic, especially later, as when Rogers talked about divorce or death. He talked about being bullied, feeling angry, being scared. And he did it in such a way that the children paid rapt attention and took it all in.

Early in his television career, the public television studio where he worked planned a sort of open house so children could meet Mr. Rogers. They planned for 500. Five thousand children and their parents showed up. The children ran right to him, and he spent most of his time talking to them, not the parents. Even when he appeared on “Oprah” he asked that no children be in the audience because he would be moved to talk to them and not the hostess. His request was ignored, and he did, indeed, put all his focus on the children.

Rogers, though gentle and kind, was also a demanding boss, who wanted everything just so for his shows. He expected those who worked with him to share his vision, at least part of it, and while he brought in incredible talent — jazz musician Johnny Costa was the leader of the ensemble that provided music — he still wanted control over almost every aspect of the show.

He understood his demands could be difficult, but what mattered to him was how the children perceived and understood his message.

Rogers saw a psychiatrist for years, to help him deal with stress. So although he was remarkable, he was very human, as well.

King obviously respects Rogers. His book is glowing, and his record of Rogers trailblazing work is impressive. The funny thing is, readers don’t hear the voice of Fred Rogers very much, as easily the first half of the book is about Rogers’ childhood and early days in television.

King talks to people he worked with, but the reader will still get the sensation they are looking at Rogers through a screen.

Yo Yo Ma and Winton Marsalis reflect on their times with Rogers, and talk about him as a singular man whose talents and passions were well focused, and who allowed others to shine, encouraged excellence and gave credit where it was due.

Photos from Fred’s childhood and his shows bring more personality to the book. Still, he seems just out of reach for the reader. We know where he came from, how he behaved, who he consulted, who he loved, who he respected, but he comes across as an icon, when he might have wanted to be remembered as a man with a vision.

King has footnotes for every fact, showing how much research he did, as well as a thorough index.

Also out this year is a documentary, “Won’t You Be My Neighbor,” about Rogers, featuring his wife, Joanne, and many of the people who worked with him. One reviewer advised viewers to bring lots of Kleenex.

Tom Hanks stars as Rogers in a new film, tentatively titled “You Are My Friend,” that will be released in October 2019. The movie is not a biopic, but a fiction created around the character of Mister Rogers.