Gary Freeze: How Christmas trees came to Salisbury

Published 1:55 am Sunday, December 9, 2018

Dr. Gary Freeze of Catawba College has made it a holiday activity the last few years to look for the historic evolution of the customs we all associate with Christmas. A couple of years ago he searched for local appearances by Belsnickel — a Germanic manifestation of Santa Claus — and this year he has looked for the advent of the Christmas tree. Below is part of a talk he plans to give at South Main Book Company on Friday, Dec. 14. Freeze will be around there to talk Christmas from 6 to 7:30, and will give a presentation at 6:30.

The originating document for the American version of Christmas — Clement Moore’s “A Visit From St. Nick” — was first reprinted in North Carolina in 1839, and its storyline spread across the state. By 1856 Elizabeth City residents knew that “good things” were “poured down the chimney and through the keyholes.” Stockings were mentioned in Wadesboro in 1858. Raleigh papers extolled the “large expenditures, etc.” in 1861.

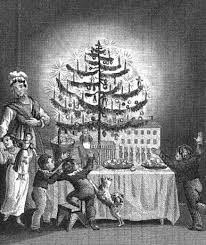

But were the presents put under trees? No! Trees seem first to have come into churches sometime in the 1850s, and the presents seem to have be put on the trees.

The first event like this was staged in 1857 by the Methodist Women’s Sewing Circle in Raleigh, who put up “a Christmas tree filled with goodies and pretties” at the nearby Female Seminary. The same activity seems to have come to other cities in the eastern half of the state, like New Bern, but there is no evidence of this in the west.

Christmas trees for most North Carolinians, like emancipation and baseball, seem to have been a product of the Civil War, initially as congregational or community fundraisers. One was held in 1863 at Raleigh’s “Deaf and Dumb Asylum” by “friends of the school.” Methodists in Goldsboro in 1866 had a three-day fair — running from Dec. 24 through 26 — where townspeople could come buy gifts and gawk at the tree. In each case, it seems, the gifts for children “were placed on the tree.” Another one in New Bern used a holly tree to hold the gifts.

This is how, like Reconstruction, Northern ways like Christmas trees came to Salisbury. The women of the local Methodist Church gave a fundraiser on Christmas Eve in 1869. “We have rarely seen a scene more pleasing,” said one patron as he surveyed “thousands of interesting toys” there. The ideas had spread everywhere. During the 1875 season, Wilmington merchant George Myers advertised “an endless variety of “Christmas Goods” and “every description of Christmas tree trimmings.”

This trend from the older “merry olde” English Christmas to the newer Santa-oriented festivities is best seen locally in the diary of the Rev. Samuel Rothrock, Rowan’s venerated Lutheran pastor. Rothrock’s faith journey through the mid-1800s chronicled the coming of the new kind of American Christmas.

On Christmas Day in 1839, Rothrock preached at “the widow [of] Daniel Agner’s” — first in English, then in German — to “a good attendance.” Almost every holiday, he was in some church on Christmas Day, most often at his base congregation, Organ, an indication that at least some local residents considered the day a religious observance. One year he started a weeklong revival, which meant that folks came to church every day of Christmas week. He addressed a temperance society meeting in 1848, perhaps to counter the more traditional carousing and drunkenness exhibited in the neighborhood. In 1852 the younger members even had “catechization” on Christmas Day.

There was little included about holidays in the diary in the 1860s, but by the early 1870s Rothrock’s experiences fell in line with those statewide. On Christmas night 1872 he “witnessed the Christmas tree at the Lutheran Church” — at St. John’s — suggesting that it was conceived of as an activity more than a gaze. In 1874 he attended a similar program at St. Peter’s, showing that the new custom had spread from the city to the country.

The custom soon spread from churches to schools. In 1878 Rothrock went to “the Elm Grove Christmas tree” and “addressed the audience.” And it became more generic. At Ebenezer Lutheran the next year he went to “the Christmas entertainment” where “sundry speakers addressed the audience.”

By 1880 Rowan residents — just like North Carolinians generally — had begun to celebrate the holiday like their children and grandchildren would well into the 20th century, with a bit of religion, an array of giving and eating, and a sense of timeless assumptions about what was actually a fairly rapid change in their culture.