John Hood: Cooper among Democratic governors receiving failing grades

Published 5:54 pm Saturday, January 5, 2019

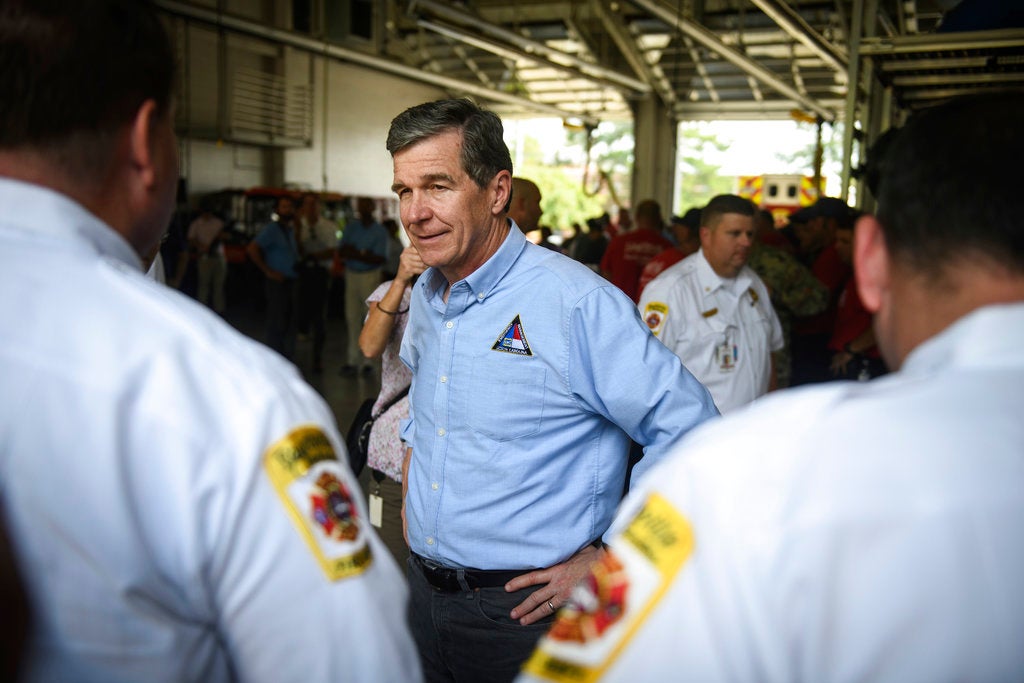

- North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper thanks first responders for their work during Hurricane Florence at Fayetteville Fire Station 14 on Thursday, Sept. 20, 2018. (Andrew Craft/The Fayetteville Observer via AP)

By John Hood

RALEIGH — Want yet more one signal that American politics has changed markedly in the past decade? Look no further than the annual report card issued by the Cato Institute to grade the fiscal performance of the nation’s state governors.

Cato is a libertarian think tank, so on economic matters you might expect Republican politicians to be more in line with Cato’s policy preferences than Democrats would be (the situation might be different on social issues). And, generally speaking, you’d be right.

But, even just 10 years ago, there were quite a few Democratic officeholders whose views on fiscal policy were moderate to conservative. Their budgets were constructed to prioritize education and other core programs without committing to reckless spending growth. Some Democratic governors proposed tax cuts to enhance their state’s economic competitiveness while giving residents more freedom to decide for themselves what to do with their money.

Employing both revenue and expenditure variables, Cato analyst Chris Edwards assigned letter grades to each governor. Of the 17 who received As or Bs in 2008, six were Democrats: Govs. Joe Manchin of West Virginia, Ted Strickland of Ohio, Bill Richardson of New Mexico, Brad Henry of Oklahoma, John Baldacci of Maine, and Phil Bredesen of Tennessee.

In the 2018 report card, however, the 16 governors earning above-average grades were all Republicans, including five with As: Susana Martinez of New Mexico, Henry McMaster of South Carolina, Doug Burgum of North Dakota, Paul LePage of Maine, and Greg Abbott of Texas. Only one Democrat, Steve Bullock of Montana, managed even a C.

Our own Roy Cooper, alas, was one of the six Democrats and two Republicans who received failing grades on the 2018 report card. Cooper deserved it, in my opinion, for the utterly irresponsible budget plan he proposed in 2018. (In fairness, you should know that I also thought the Republican legislature’s 2018-19 budget plan raised spending too much.)

Quite apart from whether you agree with the fiscal-policy preferences that the Cato Institute and I share, however, think for a moment about what these two snapshots in time reveal about the increasing polarization of American politics.

Although political parties can disappoint their hardest-core supporters by going too slowly or straying from their ideological moorings on occasion, it is essential to recognize that the Democratic Party is much more consistently liberal than it used to be, while the Republican Party is much more consistently conservative.

These terms mean different things to different people, I grant you. The term “liberal” has become an umbrella term that describes an alliance of progressives (left on economics and social policy) and communitarians (left on economics but not on social policy) while the term “conservative,” in its modern context, describes an alliance of traditionalists (right on economics and social policy) and libertarians (who often dissent on the latter).

Something like the same coalitions were evident in 2008. But the partisan umbrellas were open a bit wider, capturing a more diverse assortment. On the Democratic side, Joe Manchin is now a U.S. senator and Phil Bredesen tried to become one in 2018. But few up-and-coming Democrats are following in their footsteps.

For one thing, the Democratic politicians who inspire party activists — and who dominate the field of presidential candidates for 2020 — tend to be in Congress, not leading executive branches in state capitals. And to the extent Democratic governors are helping define the party’s current brand, they are fiscal liberals such as Jerry Brown of California (who got a D on the Cato report card), Mark Dayton of Minnesota (D), Tom Wolf of Pennsylvania (F), and Jay Inslee of Washington (F).

The events of the past two years have presented Republicans with big political challenges, no question about it. But to the extent Democrats cede both right and center to Republicans when it comes to economics, both in Washington and in state capitals, they are making a long-term bet that the public wants vastly more government and vastly more taxes to pay for it. Seems risky.

John Hood is chairman of the John Locke Foundation.