Can the heart survive a war?

Published 12:00 am Sunday, January 6, 2019

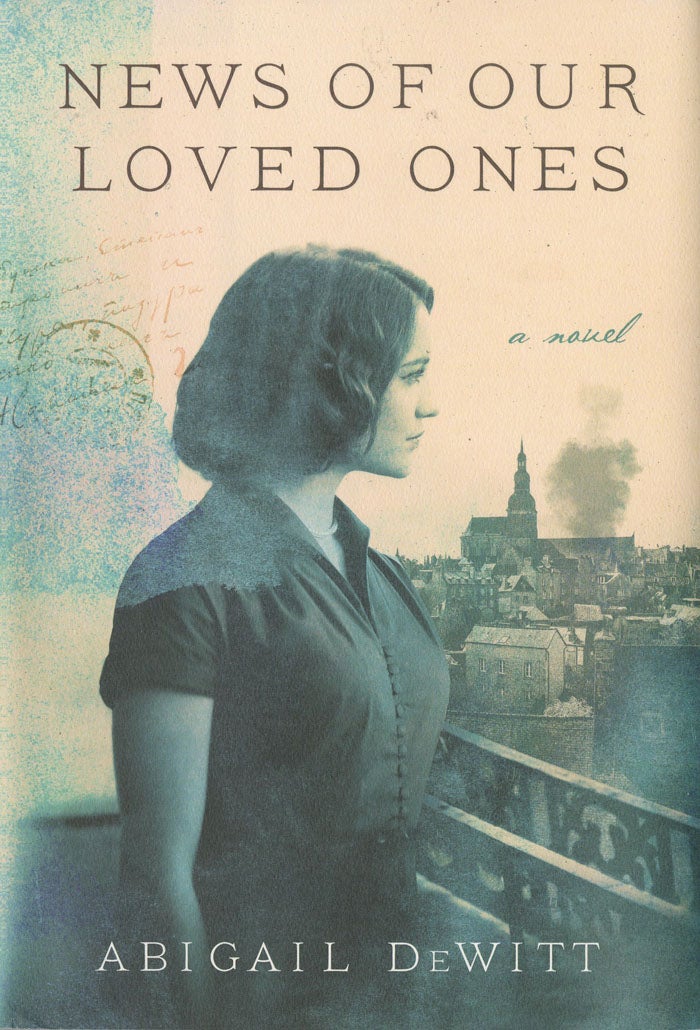

“News of Our Loved Ones,” by Abigail DeWitt. HarperCollins. 2018. 222 pp.

By Deirdre Parker Smith

deirdre.smith@salisburypost.com

I get too involved in books. I seep into the plot, picture the surroundings, smell the ashes. I hear the violin, the waves at the shore.

Abigail DeWitt’s “News of Our Loved Ones” took me to sad places, produced a concave feeling in my chest. Yet many times, the story lifted me, made me look up and marvel at humanity’s resilience. It will also make you think about race hatred and forgiveness.

DeWitt’s novel follows the Delasalle family of Caen, France, during World War II, a bit before and decades after.

The book is more like a collection of short stories of character vignettes, so it take a moment or two of reading some of it to realize who the chapter is about.

The narrators are all connected to the family. When we meet them, Oncle Henri is married to Maman. There are three daughters and two sons, and different fathers. Maman loses her first husband to diabetes.

Oldest son Louis dies in the war. Brother Simon marries a stupid woman and lives lavishly in Paris. Yvonne and Françoise look just alike, with long black braids. Geneviéve, blond and blue-eyed, has a small musical talent that saves her when the war takes half the family.

Yvonne is the dreamer; Françoise works hard. Geneviéve lives in Paris through the end of the war, marries an American musician, moves to Raleigh and has four children to whom she is indifferent. Her husband practices cello all the time. She feeds and clothes her children, but she does not indulge them.

She travels back to France every summer, insisting her children learn French and get to know their cousins.

She finds solace and comfort with a certain Frenchman — her hair dresser, she tells her youngest daughter, Polly.

Over all the stories is hope and heartbreak. The war alters everyone, even generations later. No one who survived is healed, and yet, they persist. Many tell the story again and again, as much to comprehend it themselves as to inform others.

Pain moves inward to a calloused place, and the pleasure the women have or steal covers up the old wounds.

The book is haunting, intimate and full of thoughts the characters dare not speak.

The author’s mother lived on coast of Normandy and her house was bombed on D-day; her mother’s sister died. DeWitt remembers hearing the stories again and again and remembers their trips to France. The book is her attempt to recreate and make some sense of what she learned.

Both Geneviéve and her daughter Polly feel they are not really in this world. And they both search for their places, much as Geneviéve’s surviving sister searches the rubble of their family home for her other sister’s remains.

Another character stands out, and that is Tante Chouchotte, Maman’s sister, who lives in Paris and takes Geneviéve and later, her children, into her heart and under her somewhat wobbly wings. Among them all, she, perhaps, is the real survivor.

No one can just pick up the pieces and move on. Too much lingers in the heart and the mind, or the mind plays tricks to protect the heart from unbearable emotions.

DeWitt’s language is beautiful, the emotions very real, the places — as if they’ve been remembered in a painting or photograph.

Her book will linger in your mind for a while, ruminating on the opening epigraph from Tim O’Brien: “To go home, one must become a refugee.”