‘Too valuable to throw away’: Brownfields programs a way for former industrial sites to get new life

Published 12:00 am Sunday, December 29, 2019

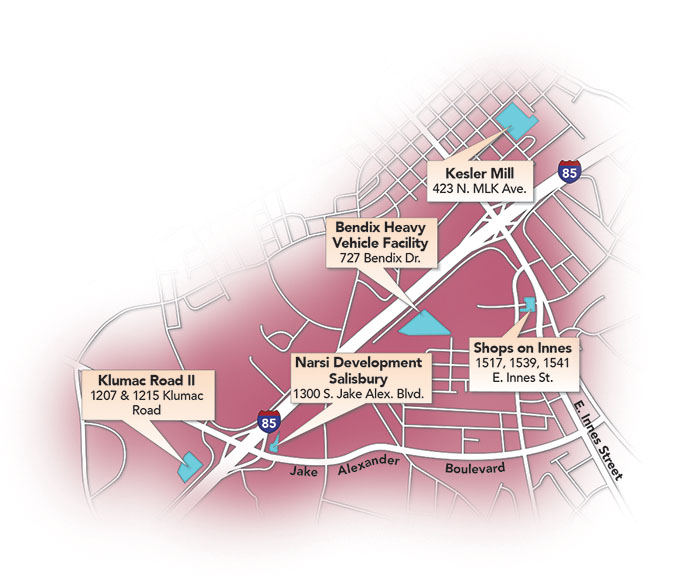

- Graphic by Andy Mooney, Salisbury Post - This graphic shows locations of several brownfield sites in Salisbury.

By Natalie Alms

For the Salisbury Post

SALISBURY — During a 2012 City Council meeting, the late William Peoples, a community activist, said those living around the former Kesler Mills site were “helpless.” On their own, they couldn’t clean up the huge piles of debris that contained asbestos at the old textile mill.

“It’s a travesty that they’ve had to endure this for so long,” said Peoples, who died in 2017.

That site at 423 N. Martin Luther King Jr. Ave. served as location for industry from 1895 to the early 2000s. Kesler Manufacturing, Fieldcrest Cannon Plant No. 7, Pillowtex and others all occupied the site for a time. The last structures were demolished in 2009 and since then, the land has sat vacant.

The ghost of its industrial past left the site with pollution. For now, fences, cameras and drone surveillance by the city prevent entry and keep it and the people around it safe. The city is waiting to hear back on an application for a federal cleanup grant. Previous applications have been unsuccessful.

The Kesler Mill site is an example of a “brownfield,” or property that’s difficult to redevelop because of pollution or the potential presence of pollution after industries change or leave, according to the Environmental Protection Agency’s website. Underground storage tanks, for example, can leak petroleum into the surrounding soil, creating a brownfield.

‘Roadblock to development’

Even if the groundwater and soil turn out to be pristine, places that once housed industry can still be considered brownfields because of the fear or perception of contamination, said Stan Meiburg, director of the Master of Arts in Sustainability program at Wake Forest University. He worked as the acting deputy director of the EPA from 2014 to 2017 as part of his 39-year career in the agency.

Kyle Harris, former city planner for Salisbury, added, “There’s a big perception issue, especially if you’re redeveloping in an area where there is documented proof of potentially contaminating, intense industrial uses.”

Knowing what is actually on a site is crucial to giving a brownfield new life. It would be a liability to redevelop something without knowing if it’s contaminated, Harris said. The pollution can sometimes determine how a piece of land can be used.

“Even the risk of something being there can be a roadblock to its redevelopment,” he said.

The former Kesler Mill site isn’t the only brownfield in Salisbury.

There is also Bendix Heavy Vehicle Facility, Narsi Development on South Jake Alexander Boulevard, as well as two sites on Klumac Road and two on East Innes Street. All are listed as brownfields on the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality website. That list only includes sites that are registered under the state program. To make it on the list, officials need to know if it is polluted in the first place. Developers, city officials and state and federal agencies all play a part in that complicated process. From there, various factors play a role in if, when and how brownfields get cleaned and redeveloped.

Sometimes, developers will clean up brownfields independently of any government action, despite the cost and liability. The pace of growth in a community, the cost of the cleanup and the motivation of the owner could all play a role, Meiburg said. Federal programs offer assistance that’s often critical in the process of clarifying if and how a site has been polluted.

Legislation

The first government involvement in brownfields was the 1980s Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), more commonly known as the superfund law, Meiburg said. It regulates hazardous waste sites and holds companies that polluted them responsible for cleaning them as well.

However, it only applies to brownfields of a relatively large scale, not less polluted and smaller brownfields like ones in Salisbury. Until new legislation came around, however, liability that came with owning a polluted property remained.

“These became a real barrier to development,” Meiburg said.

A series of EPA programs and federal laws sprang up to address the gap. These programs provide grants that fund the assessment of these sites and their cleanup and can be seed money in communities where there isn’t a high enough demand for cleanup, according to Cindy Nolan, Brownfields section chief for the EPA Region Four, which includes North Carolina and other states in the Southeast.

State-level legislation also addresses liability. North Carolina’s brownfields program changes the math of who is liable for the pollution and gives potential developers tax breaks and limited liability if they agree to clean up a brownfield.

The ultimate goal of these programs is to spur redevelopment and economic growth by removing barriers to building on brownfields.

“People should care about it for selfish reasons,” Meiburg said. “Land is too valuable to throw away.”

In a state with growing development pressures, a factor working in favor of redeveloping brownfields is that infrastructure often already exists there. Meanwhile, building on undeveloped sites disrupts habitats and stormwater runoff. The EPA website touts its brownfields program as promoting job growth and increasing local tax bases. For all these reasons the program has been popular on both sides of the political aisle, Meiburg said.

Local projects

If the potential presence of pollution obstructs redevelopment of brownfields, the city of Salisbury works to get a clear picture of what’s on the land, Harris said.

“The overall global purpose of our program is to reduce uncertainty related to what’s there on any of the sites we’re working on,” Harris said.

EPA grants are critical in this mission. The city has received two assessment grants, which fund the process of finding out what pollution exists. Some financial institutions require such assessments before facilitating a transaction on brownfield land.

Salisbury’s first assessment grant was received by the city in 2014 and was for three years. With the grant, eight local brownfields were given phase one and phase two petroleum and hazardous materials environmental assessments, said Hannah Jacobson, community planning director for Salisbury. Those sites included 201 East Innes St., the Empire Hotel, Kesler Mill, Monroe Street School, the Washington Building, and Schaffer Iron Works.

More recently, Salisbury received another $300,000 three-year assessment grant in 2018.

Developers can approach the city about having a site examined, and the city can broadcast the program to make developers aware of the program. The city is currently working on a new brownfields website, salisburync.gov/brownfields, Harris said.

“There’s no reason for someone who’s potentially going to redevelop a site to not come to (the city) and ask for assistance,” Harris said.

So far, City Consignment, Hughes Supply, Star Laundry and owners of a site at 602 S. Main St. have contacted the city about being assessed, Jacobson said. Additional funds are available. One of the targets for additional assessments is the South Main Street corridor, between the Empire Hotel and Chestnut Hill cemetery, Jacobson said.

The hope, Jacobson said, is that the brownfields grant can work in tandem with other projects and that focusing on one area maximizes available grant money. The South Main Street assessment, for example, will occur as the city is planning a redesign and improvement of Main Street, its ongoing downtown incentives program and the Empire Hotel redevelopment.

“We’re trying in part to prioritize downtown as part of an economic development strategy,” said Harris. “It’s really a city-wide effort.”

Nonetheless, Kesler Mills still contains a pile of debris seven years after Peoples complained. And a 2015 EPA assessment found areas of soil contamination and asbestos.

The property was deeded to FCS Urban Ministries in 2007 before being taken over by the city in 2019 — a prerequisite to applying for a grant under the EPA brownfields program that would give the city resources to clean the site up.

In 2018, the city applied for a cleanup grant, but didn’t receive it and no cleanup grants were given in North Carolina that year. There were more applications than money to go around, Harris said.

Part of this is due to the national political backdrop, since the program is funded by the federal government. Although President Donald Trump has verbally praised the superfund and brownfields programs, every budget that he has proposed since being in office has included cuts to the programs — part of a broader landscape of EPA cuts.

Salisbury officials hope to hear back about the latest application, submitted in early December, in April or May 2020.