Salisbury’s Scheid becomes city’s newest centenarian

Published 12:00 am Sunday, January 26, 2020

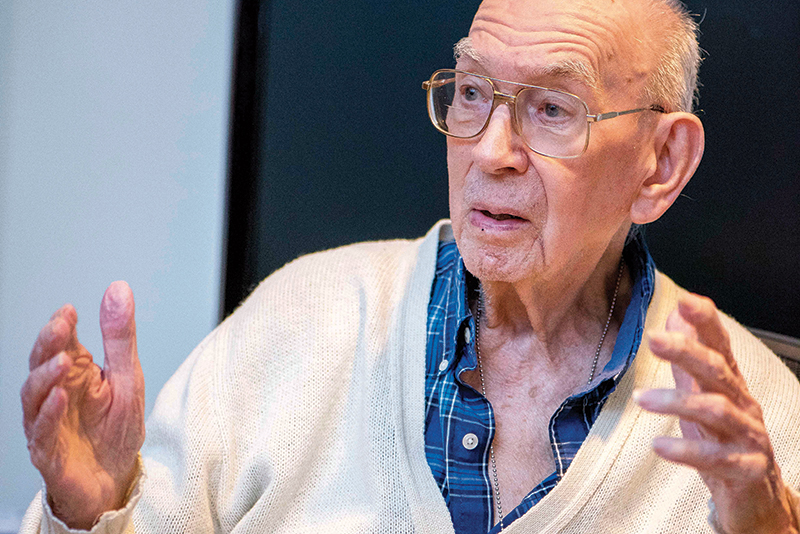

- JON C. LAKEY/SALISBURY POST Charles Scheid grew up in a town in Pennsylvania where the Piper Aircraft company was based. Working at the company, Scheid was able to log thousands many flight hours before joining up to fly airplanes in the US Military during World War II.

SALISBURY — A lifetime ago and hundreds of miles away, Charles Scheid learned a lesson.

If you wanted to find Native American arrowheads in central Pennsylvania, go into farm fields after a spring flood receded and crawl down the rows. Following a good rain, the arrowheads would often stick a few inches out of the ground.

“One row was one mile long and I would do every row in the farms,” Scheid says.

That was in the 1920s, when Scheid was just a child. Today, he turns 100 and still recalls his life’s memories with sharp detail. He was born north of Pittsburgh but his life and his work took him across the world. He built Piper Aircraft planes in Pennsylvania and delivered them across the country and, later, to other countries while serving in the Air Force during World War II.

His career took him to New York City, Chicago and, when choosing where to retire 30 years ago, Scheid found Salisbury.

So, how does it feel to be 100?

“It feels about like 100 would,” he said.

And what’s the secret to long life?

“I tried everything once, smoking and everything once, but I hated it,” he said. “It was obvious that what people were doing was bad for them, but they didn’t have the guts to quit. I didn’t require the guts because everything tasted terrible.”

He takes pride in what’s been a long and varied life, saying, “You can’t put Charlie in a box.”

Scheid, born in 1920, spent his early years living at Thorn Hill School for Boys, a reform school for those who misbehaved or had no home. He found himself there because his father was a member of the staff. Though, the family left when he was 4 because “it was pretty hard to tell whether I was part of the group, some of the bad boys or not.”

The family’s move took them to Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, where Scheid learned his lesson about finding the best arrowheads. But Scheid said he didn’t have much of a childhood. After his father died when he was young and even though his mother remarried, he often found himself taking care of her.

Scheid’s mother had multiple sclerosis.

“When I would take care of her at night, she would bang on a pipe with a shoe. I would run down and she would get a hold of my shoulders and I would drag her to the bathroom three times every night,” he recalled.

He went to live with his grandparents during the depths of the Great Depression.

One of his first jobs was as an engineer at Piper Aircraft Corp., founded in Lock Haven. He also flew planes for the company. But his time there is perhaps most notable because that’s where he met his wife, Mary Emert, who worked in the parts department.

“Have you seen the girl in the parts department,” Charles recalled his friend asking.

His response: “I don’t look for girls. I’ve got enough problems at home.”

One of his friends suggested that Charles ask her on a date, and his method of choice was to type a note on her typewriter that she later found.

Their first date was a rainy night, and Charles recalled borrowing his stepdad’s car to take his future wife to a movie. It had a leak in the roof, he recalled, but that wasn’t so bad because it meant his date needed to move closer to him in the car. After the movie, they went to the drug store for milk shakes.

JON C. LAKEY/SALISBURY POST Charles Scheid married Mary in 1945.

The couple dated for about three years and got married in 1945 in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, while Charles was home on leave from the U.S. Air Force — where he was primarily responsible for flying different models of planes all or part way to their completed destination.

“Wherever a plane was sitting and it had to go from A to B, we would deliver it,” he said.

As a teenager, he attempted to get his congressman in Pennsylvania to appoint him to the U.S. Military Academy or the Naval Academy, but never received an appointment.

In Lock Haven, Charles and Mary had five children — Lori, Charles, Geoffrey, Kevin and Linn. In the mid 1960s, the couple moved to New Jersey and Schied worked in New York City on the 78th floor of the building known as “30 Rock,” or 30 Rockefeller Plaza. There, he worked for the Singer Corporation. Several years later, they would move to the Chicago metropolitan area before settling just outside of Salisbury, in the Woodbridge Run neighborhood on Mooresville Road, after retirement.

Their house in Salisbury, daughter Lori Pesta remembers, was “exactly like one they live in while in Chicago.”

Charles’ wife, Mary, died in 2010 at the age of 89.

Josh Bergeron / Salisbury Post – Family members of Charles Scheid gathered Saturday to celebrate his 100th birthday. Pictured from left are Scheid’s son Charles; daughter Lori; Lori’s husband Chuck; son Linn; and son Kevin.

He now lives in Trinity Oaks in Salisbury, where he was joined by his children Saturday for a birthday celebration. The family is spread out across the country, with one living overseas, too, but they keep in touch by using technology. Video conferencing program Skype, in particular, Lori says, has been useful. For much of his life, Charles was a serious user of amateur radio, also known as ham radio, and that passion has spilled over into the internet, too, with a computer setup in his apartment at Trinity Oaks.

Linn, who is the youngest of the children, said the family is proud that their dad reached 100 years and that all five of the siblings are likely to make it to 100, too, because of the family’s good genes.