As vacant seats increase, school closures remain unpopular in Rowan-Salisbury

Published 12:10 am Sunday, February 9, 2020

By Carl Blankenship

carl.blankenship@salisburypost.com

SALISBURY — Closing a single school could save the school district, conservatively, $500,000 a year, according to leadership of Rowan-Salisbury Schools, a district that’s seen a steady decline in enrollment.

That is money that could be used to hire more staff members, pay them more and provide support for other facilities and programs. Assistant Superintendent of Operations Anthony Vann said closing a school could also free up funds that would allow the Rowan-Salisbury Schools district to take care of critical capital needs at other schools. Each facility has maintenance costs and utilities that the district has to pay.

Not counting mobile units, the Rowan Salisbury School System has 5,000 empty seats in a district that serves about 18,800 students. About half of those empty seats are in the elementary schools, as the district has lost about 1,900 students over the past 15 years. The district could add more than 2,000 new students with the facilities it has now and still be under 90% capacity.

“Some folks prefer 85% capacity, some folks look at 90% capacity,” Vann said. “I think there are different thought processes there, but I think if you’re closer to the 85 or 90% capacity, I think it does give you some flexibility with students coming in.”

Each district in the state receives per-student funding. When the number of students declines, so does the funding. But the facility costs remain unless the district closes schools.

The district was funded at $5,734.34 per student for this school year. If the district still had the 2,000 students it lost over the past 15 years, that would add about $10 million to the district’s more than $200 million budget.

Superintendent Lynn Moody said teachers will not lose their jobs following a closure, since the district uses natural attrition as people retire or leave the district. If schools close, there is room for the faculty in other schools in the district, Moody said. Even with the drop in student numbers, the district is still actively seeking more teachers.

It is hard to pinpoint exactly why a district loses students, but Vann cited home schooling, charter schools and private institutions as alternatives that draw some families away from traditional public schools. “Renewal,” which began this school year, gives the district a number of “charter-like” flexibility options.

Cities and counties can raise taxes to address a funding gap if the controlling board sees fit, but school districts cannot. District funding is cobbled together from several sources. The state and federal governments fund the district, though federal money passes through the state. Local funding primarily comes from the county, which also pays for capital costs such as new schools.

Despite the factors that favor closing schools, the RSS Board of Education has struggled with the issue. Plans have been created, abandoned, modified and revisited for years with little movement toward hitting a desired percentage of seats filled. Every time a school’s name has come up for closure, staff, parents, students and community members speak against the proposals. But the district’s population is still on a decline, with some buildings built for 400 or more students now holding less than 300.

Moody said she wouldn’t suggest school closures if she didn’t think it was in the best interest of the district.

Community opposition

The most recent examples are Overton and Enochville elementary schools.

When Overton’s closure was worked into a now-defunct plan to perform major renovations on Knox Middle School, the community response led the board to the current plan to consolidate the two schools into one K-8 facility on land between them. The project has an estimated cost of $50 million and moved to the design phase at the same Jan. 27 meeting when administration presented some school closure options to the board. One closure option looked at the possibility of closing Henderson Independent High School, which the administration was still studying and had no recommendation on. The other was a recommendation to start the closure process for Enochville.

Several teachers and a community member came to speak in favor of keeping Enochville open, describing the great things happening at the school.

At the meeting, Moody said Enochville’s name was pulled only because it has the lowest number of students enrolled in an elementary school. The board did not move forward with the closure, instead asking staff to revisit a chart for elementary schools created by a Capital Needs Committee in 2018.

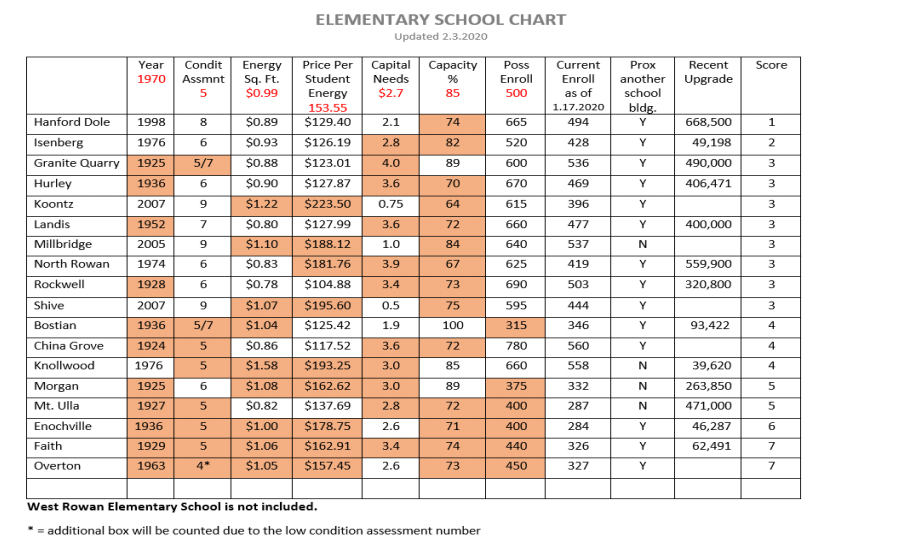

The 2018 chart ranked schools based on the year the facility was built, condition, energy cost per square foot, energy price per student, capital needs, capacity and possible enrollment. Schools that did not meet thresholds set for each of those categories were flagged, and schools with enough flags were placed below a cutoff line would be looked at for possible closure.

That chart had six elementary schools, three middle schools and two high schools that fell below the cutoffs. All of the schools on that 2018 list are still open. Knox, Overton and Henderson were all below the cutoffs. Enochville was not.

The updated version of the chart will be shown at Monday’s Board of Education work session and it no longer has a cutoff line. But Enochville now ranks near the bottom, with six of seven possible flags. Overton also has six of seven flags, but will be closed anyway pending the completion of the new K-8 project. Overton and Faith elementary are the only schools with seven flags.

Since the 2018 study, Vann said, Enochville has lost 100 more students. On the chart to be shown Monday, Enochville has the lowest number of students — 284, Mt. Ulla Elementary has 287.

‘Lose good people’

In the not-too-distant past, the district closed a pair of schools — Cleveland and Woodleaf elementary schools — and consolidated their students into what is now West Rowan Elementary. If the Knox and Overton project goes through, it would consolidate another pair of schools. But future decisions could also involve closures without consolidation into a newly built facility.

The board is currently looking at closures two school years from now. And a school with its fate hanging in limbo can cause them to, effectively, close early by themselves, Moody said. Enochville’s name was drawn for possible closure about a year ago. Since then, the student population has declined significantly. Moody pointed out that faculty can leave and parents can move their children to other schools.

“Anything that’s disruptive or unknown always has that potential to lose good people,” Moody said.

Meanwhile, what does the district do with a school once it’s closed? Many of the schools are more than 50 years old, and represent decades of history. Demolition has a cost as well. Some closed schools can be repurposed into something else.

At the moment, only one elementary school is on the chopping block. Henderson Independent High School was formerly an elementary school but now serves a small, fluctuating number of older students.

School board member Jean Kennedy, whose two oldest daughters attended Henderson Elementary, says she’s worried about history associated with the facility’s closure.

“I know we need to economize and save money, but I just hate to see these buildings demolished, and I know that’s what will happen to Overton and Knox because of the type of structure that’s supposed to be erected on those grounds,” Kennedy said. “Henderson could easily convert into some type of community building.”

Kennedy pointed out there is an old elementary school that is now a community center on Dukeville Road and there are old school facilities all over the state that have been converted for other purposes.

Sometimes, schools close and turn into something else for the community they serve. Other times when schools close, the buildings are not demolished, they sit empty, deteriorate and turn into eyesores.

“In my former district, a new school was built and the old facility was left standing in the community,” Vann said. “The community wanted to leave it there and not demolish it, and a few years later everyone wished that it had been torn down.”

Systems choose to either tear down or sell off old facilities, but often the cost of upfitting an old school to something modern isn’t cost effective. A buyer may want the land but not the structure on it.

Vann said people on both sides of closure arguments have strong opinions, with some wanting to retain their community schools. Others want their tax dollars to be used wisely.

“Community schools are important, no doubt about it,” Vann said.

For Board of Education Chairman Kevin Jones, it’s “a difficult spot to be in,” but it’s no necessarily a “no-win” situation.

“I hope we can navigate through and make it beneficial to the most students in our system,” Jones said.