How a house unmade and made a family

Published 12:00 am Thursday, February 13, 2020

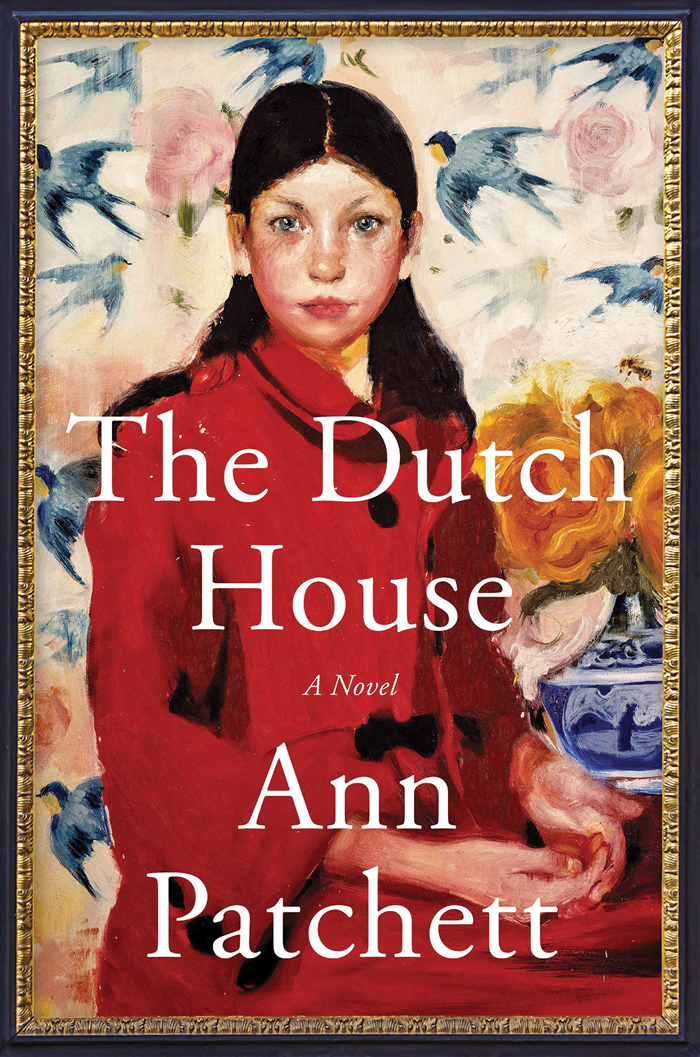

“The Dutch House,’ by Ann Patchett, HarperCollins. 2019, 352 pp.

By Deirdre Parker Smith

deirdre.smith@salisburypost.com

“The Dutch House” is and is not the biography of a beautifully ornate home on a hill outside Philadelphia.

Told through the eyes of Danny Conroy, who lived there, “The Dutch House” is a story about relationships, the complexity and confoundedness of love and the people who bind us to our past.

Ann Patchett, one of America’s favorite authors, fills the book with emotion, yet keeps it under control. Danny, the narrator, rarely strays from a steady path of telling the story of those who lived in that house. The house itself is mute, simply existing, aging more gracefully than most.

Danny and his sister, Maeve, were raised in the house, for a time. It is a mansion their father, Cyril, a real estate mogul, bought from bankruptcy as a surprise for his wife, Elna.

Elna doesn’t just disapprove. She feels awful in the opulent house, ashamed of its elegance and expense. She thinks of herself as the poor relation, not a resident, not a person who needs servants and not part of the story.

So she removes herself, leaving Maeve, 10, and Danny 3, with their father, off to India to serve the poor.

Because Cyril much prefers business over family, Maeve raises her brother, with the two women who work there, Jocelyn and Sandy. And those women could not have loved those children more. It’s just that, with Cyril’s work habits and concerns, love never warms as it could.

Maeve and Danny had a nanny, once, oddly named Fluffy because they could not pronounce Fiona. In a pique of anger one day, Fluffy hits Danny in the face with a hot spoon, leaving a mark, and she is forever banished, another loss, like their mother.

The children live with little affection but each other’s, but the influence of the two servants surely has something to do with their ability to not just survive their mother’s abandonment, but their drive to succeed.

Maeve is a math wizard who could literally become anything, were it not for the times, the 1950s and ‘60s, and her roles as substitute mother and keeper of memories.

Young Andrea, a widow with two little girls, waltzes into the house — ostensibly courting their now divorced father, but really in passionate love with the glass-fronted house with a clear view of the back yard from the front door.

Andrea’s girls, Norma and Bright, are too young to understand what’s going on, but as Andrea’s appearances become more frequent, Maeve and Danny realize, with some horror, that Andrea is to become a permanent resident, and their stepmother.

From there, predictable wicked stepmother things occur, but Andrea is very careful in her machinations, pushing her husband’s children into smaller roles and smaller rooms, making way for her own children.

Once she rids herself of Maeve and Danny, the reader won’t see her again, not for a very long while.

Maeve finishes Barnard College, then comes home to help a local man with his frozen vegetable business.

When she realizes she and Danny are to be left not just homeless, but penniless at their father’s death, Maeve carefully studies the will and trusts, and creates a plan for Danny to go to school for as long as possible, to go to medical school, and bleed as much money as possible from the awful Andrea.

Danny is nothing if not pragmatic, and, as the narrator, that comes across. Danny doesn’t want to be a doctor. He wants to follow in his father’s footsteps and work in real estate. He knows how much money can be made, with the right investments, and it takes fewer hours and much less blood, sweat and tears to buy and renovate a building than it does to renovate the sick.

Maeve is stung, but as long as he spends the money, she’s satisfied.

Years after their exile from the Dutch House, they repeatedly park across the street to look at it and talk about how things were; not much about how things are, or could be.

They are both stuck in that house, though they’ve long since left.

Danny muses, “like swallows, like salmon, we were the helpless captives of our migratory patterns. We pretended that what we had lost was the house, not our mother, not our father.”

Maeve, a fascinating personality, is seen only through Danny’s eyes. Her thoughts would be fodder for a parallel book. Maeve has a fire burning inside, while Danny was “asleep to the world. Even in my own house I had no idea what was going on.”

Danny meets Celeste, a head of blonde curls, who is determined to marry a doctor, even if it’s just letters after his name. She and Maeve blame each other for every misfortune in life, and Danny is stuck. He wants his wife to be happy, but he needs to be with and care for his beloved sister. Celeste never quite understands the depth of the bond.

Patchett often writes about difficult relationships among family members, children not raised, but grown. Here she uses a sort of Hansel and Gretel fairy tale to raise questions about love and nurturing, care and ignorance.

The story makes a wide turn back to further test Maeve and Danny’s strong hold on each other, to question what has happened to them and how they will move forward or accept what reality offers them.

Overall, the book is full of sentiment, but pragmatic.

This is what we were dealt. This is how we embrace it, mold it, make it part of us and not part of us. This is what we let go of. These are our sacrifices.