1964 East Rowan baseball: No fair balls against Robbins

Published 12:00 am Tuesday, August 4, 2020

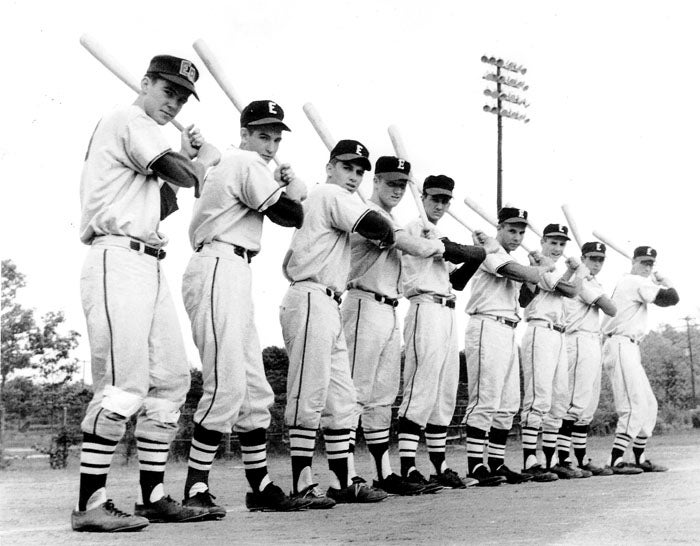

- East Rowan's lineup in 1964 (Left to right): Bobby Gulledge, Mike Bingham, Danny Williams, Richard Kluttz, Phil Robbins, Ronald Kirk, Julian Sides, Carless Lowman and Phil Bernhardt.

By Mike London

mike.london@salisburypost.com

GRANITE QUARRY — The staged photo published in the Salisbury Post is almost comical, but it accurately told the story of what happened.

Phil Robbins is winding up to throw a pitch to catcher Carless Lowman, while seven East Rowan teammates sit on the field, gloves on the ground, arms folded like they don’t have a care in the world.

Robbins was a lefty who had a fastball and curveball that could make life very boring for his outfielders — and sometimes his infielders.

In a game against Monroe in Granite Quarry on May 12, 1964, Robbins not only pitched the first of his three high school no-hitters, he didn’t allow a single fair ball to be hit.

Monroe’s lead-off batter walked to open the game. Robbins picked him off.

Robbins struck out the the next nine men he faced, with zero contact, not even a foul ball.

Phil Robbins didn’t allow a fair ball to be hit in a game he pitched against Monroe in 1964. Carless Lowman is the catcher.

Normally Robbins, who wasn’t physically imposing at 5-foot-11, 155 pounds, mixed curves with his heater, but on this night he had a little extra zip. He stuck with the fastball and just blew it by people. His fastball had natural movement and acted like a slider. It bore in on the hands of right-handed hitters.

“Quite a few of them tried to square around and get down a bunt to break up the no-hitter,” said Dan Williams, a retired F&M Bank president who played third base for the Mustangs. “A few fouled bunts off, but no one was able to get one fair.”

Robbins would strike out 19. In all, Monroe managed to poke nine foul balls in the seven-inning contest, but no fair ones.

The only putouts recorded by anyone other than Lowman were by first baseman Phil Bernhardt. He made the tag on the first-inning pickoff play and grabbed a pop up in foul territory in the seventh.

Monroe is the game Robbins is most remembered for because of the absence of contact, but he may have pitched even better games against stronger competition. He pitched some gems that he lost.

East’s young coach Burl Morris, a Concord native, had been the catcher for East Carolina’s national champions in 1961. He arrived at East in 1962 and the Mustangs, led by pitcher Dale Lefler, went all the way to the Western North Carolina High School Activities Association championship game. East lost that one, 5-4, at Cherryville.

In 1964, the Mustangs were ready for another run.

“I played a lot of baseball for a lot of coaches, but Coach Morris was the best coach I ever had,” said Williams, who went on to play four years at Appalachian State. “We were well prepared for every possible situation that might come up in a ballgame. Everyone knew their job on every ball put in play. Everyone knew where he was supposed to go. If we had bad weather, we practiced in the gym, brought out the rubber bases and drilled some more.”

Morris shook up some things.

In its early days, East played baseball home games on campus, but Morris made the move to the field right in Granite Quarry — the field we now know as Staton Field. The Granite Quarry field was upgraded with lights, fencing and a scoreboard and fans had a grandstand to cheer from. The shift in venue dramatically altered East’s fan base. Instead of playing afternoon contests in front of parents and friends, East played night games in front of hundreds of fans. The crowd for the Monroe game was estimated at 600.

East had a solid team, with second baseman Bobby Gulledge and left fielder Mike Bingham at the top of the lineup, and with Williams, center fielder Richard Kluttz and Robbins in the middle. Shortstop Julian Sides, a wizard with a glove, anchored the defense.

“The North Piedmont Conference was a very strong league that year, and there weren’t many easy games,” Williams said.

East lost one of those scraps – 4-3 in nine innings to rival West Rowan. That was Robbins’ only setback of the regular season.

Morris depended heavily on the slim southpaw. East would play 19 games in 1964. Robbins, frequently working on two days rest, would hurl in 17 of them.

“Phil was strong,” Williams said. “He could bounce back quickly from a start and pitch again.”

As a sophomore standout on a mostly senior team in 1964, Robbins struck out 157 batters in 102 innings.

That Monroe masterpiece occurred late in the regular season and clinched a tie for first place for the Mustangs. Then they had a breezy victory to officially take the NPC title — an 8-0 romp at Children’s Home of Winston-Salem. Robbins only had to pitch four innings. He allowed one hit.

Next for East was a showdown against another county team, South Rowan. That was in the Piedmont championship game that would be played at Newman Park.

South had survived a wild, see-saw struggle to take the SPC. South tied for first, and then beat Thomasville in a do-or-die playoff.

It was a banner year for Rowan County baseball — with 15 players making All-NPC or All-SPC.

The key man for South Rowan was fire-balling pitcher Tony McGalliard, who had already thrown two no-hitters that season.

The marquee pitching matchup brought out the best in Robbins in East’s 4-0 victory. He struck out 12 and pitched a one-hitter. McGalliard also struck out 12, but East played tighter defense.

“We took the team bus out to Newman Park,” Williams said. “We were excited after winning and Richard Kluttz and I pulled out the steps and got up on the roof of the bus for the ride home. There was always a policeman stationed at the square in downtown Salisbury. He stopped the bus and made us get back inside.”

Another huge mound matchup loomed for young Robbins, who had just turned 16. East made a road trip to Shelby for the WNCHSAA championship game.

That championship game was played on May 22, so Robbins had three days rest following the South game. East took hundreds of fans and the pep band to Shelby.

The opponent was a young man who wouldn’t turn 17 until September of 1964, but he was fast becoming a legend in the North Carolina foothills and a favorite of pro scouts. Shelby junior Buford Billy Champion Jr. (he answered to Billy) had a breaking ball and a knuckleball, but his bread and butter was a fastball that he probably threw harder than any high school player in the state.

East knew it had a tough task ahead, but the Mustangs were adept at manufacturing runs, even against the toughest hurlers.

“Coach Morris worked a lot on small ball — the bunt-and-run, the double steal, the delayed steal,” Williams said.

Champion was bigger than rumored. The Post’s scouting report said he was 6-foot-1, but he was 6-foot-4.

Top of the first — East had a golden chance to jump ahead. Gulledge looped a single, and Bingham smashed a single to start things off. But Champion struck out the next two. Then Robbins hit a ball hard, but Champion plucked his liner up the middle out of the air to end the threat.

Robbins twisted his foot in the second inning, but he was able to stay in the game.

Sides made spectacular defensive plays in the second and third innings. It was still scoreless going to the bottom of the fifth. That’s when Shelby bunched three hits and two infield errors to score two runs.

From the second through the sixth, East didn’t get a baserunner against Champion, who had pinpoint control.

But then East came to life. Williams lined a single to right to lead off the seventh. Then Kluttz lined a single to left.

“Robbins was next, and he tried to bunt, but he missed the pitch,” Williams recalls. “Champion wound up, didn’t pitch from the stretch, so I stole third easily. On the next pitch, Richard stole second and we had the trying runs in scoring position with no outs.”

Champion didn’t worry much about the baserunners, only the hitters. He poured fastballs past Robbins, pinch-hitter Bobby Lowman and Sides, and it was over. Shelby won 2-0.

“Whiff, whiff and whiff,” Williams said. “He was really tough.”

Champion, who was 8-1 that season, struck out 14 Mustangs with no walks in a game viewed by an estimated 1,200 fans.

Like Champion, Robbins (13-2) allowed four hits. He struck out five and walked one. Just as it had in 1962, East came up a little short in the title game.

Heartbreak would happen one more time to Morris and the Mustangs in 1966. As a senior, Robbins led East to another WNCHSAA title game. East lost that one 3-2 in nine innings to R-S Central on Shelby’s field. Robbins had thrown a ton of pitches and Morris turned to the bullpen. A wild pitch by a reliever brought home the deciding run.

•••

At least five of the 1964 Mustangs went on to play college ball. At Appalachian State, Williams’ teammates included two of the Shelby players he’d battled against. Sides played at Lenoir-Rhyne. Kluttz went to East Carolina for football, but then transferred to Catawba to play baseball and football. Gulledge played for Joe Ferebee at Pfeiffer. Robbins’ best days on the mound were for East Rowan, but he pitched for a Gardner-Webb team that made the national junior college tournament in 1967. His 5-11 stature was the reason he was never drafted by MLB. He enlisted in the U.S. Navy and went to Mitchell College when he returned from service. He got married in 1974. His son, Jake, a tall right-hander who starred at Myers Park High in Charlotte, pitched in the big leagues with the Cleveland Indians in 2004.

•••

Williams said three of the 1964 Mustangs have passed away. Bingham died young in a construction accident, while Bernhardt died of a heart attack. Sides passed away in June of this year.

•••

Champion’s baseball saga continued for many years. He starred for Shelby American Legion Post 82 from 1963-65. Twice he struck out 19 batters in a Legion game.

In 1965, as a Shelby High senior, he struck out 21 Hickory batters in a WNCHSAA semifinal that went 10 innings. His catcher swears he was throwing 95 miles per hour as a senior. Some insist he was throwing even harder than that.

In the 1965 WNCHSAA championship game, the final high school game Champion pitched, Davie County and ace John Parker beat him 1-0 at Rich Park. Champion struck out 12, but Parker fanned 14. Parker was 11-0 that season with 158 punchouts. Major League Baseball held a draft for the first time in 1965. The Philadelphia Phillies chose Champion in the third round and Parker in the fourth. They started their pro careers together on the same team in South Dakota. Nolan Ryan lasted until the 10th round of that 1965 draft.

Parker made it as far as Triple A, but he didn’t get a shot in the majors. Champion rose through the Phillies farm system. He was ERA champ in the Northern League in 1965 and the Carolina League in 1968. He reached the majors with the Phillies as a 21-year-old in 1969. He pitched in 202 big league games before retiring in 1977 to coach and scout. He died at 69 in Shelby in 2017.