Track: Barger brothers battled for a championship in 1966

Published 12:00 am Sunday, August 16, 2020

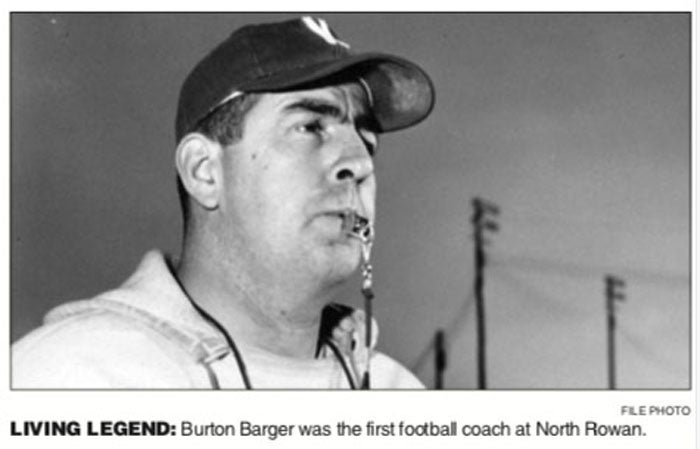

- Burton Barger

By Mike London

mike.london@salisburypost.com

CHINA GROVE — It’s an amazing true story that should be made into a movie.

Rowan-born brothers were coaching the teams going head-to-head for the 1966 Western North Carolina High School Activities Association track and field championship, where everything came down to the final event.

Change was in the air that day in Shelby. Integration and Black athletes were just beginning to be a factor in WNCHSAA track and field.

The defending champion North Rowan Cavaliers were a key man down the day of the championship after a tragic accident. The Cavaliers also were aware that win or lose on the track, they were losing the coach who had built the program.

The Hickory Tornadoes, one of the power schools in the WNCHSAA, track and field champions in 1962 and 1964 and guided by a man who was stacking up titles in many sports, were ready to sweep the Cavaliers aside.

The Barger brothers, the third and fourth of seven children were raised in a rock house near Bostian Crossroads in southern Rowan. They came into the world two years and four months apart, but they were only separated by a single year in school.

That meant the siblings looked after each other, but it also meant they competed with each other. They had their scraps growing up.

Burton Barger was born on Sept. 10, 1919, so he was closing in on 20 years of age when he graduated from China Grove High with the Class of 1939.

Frank Barger, born on Jan. 4, 1922, was part of China Grove’s Class of 1940.

They were teammates on championship teams in high school.

Burton, not surprisingly, given his age, was the much larger star in high school. He was big but swift, a center fielder who captained the baseball team, powered his way to the hoop for the basketball squad and scored the bulk of the football team’s touchdowns as the fullback. As a senior, he sparked a 47-0 victory against rival Landis.

When he graduated, everyone believed Burton had what it took to make it all the way to the top in baseball. That was the sport he loved best.

Frank was a football lineman and a baseball pitcher and first baseman. He wasn’t on the basketbal team, but as a senior he would emerge from his brother’s considerable shadow to lead the baseball and football squads.

Grace Barger, their sister, was a sophomore at China Grove when Burton was a senior. She was the school’s best female athlete. It was an athletic family

Duke was interested in Burton and Burton really wanted to go to Wake Forest, but the local minister steered him to Lenoir-Rhyne. Frank would follow his big brother to Hickory a year later.

Athletics and education for both Bargers would be interrupted by service in World War II.

Burton became part of the U.S. Army on Feb. 17, 1942. By June, he was sailing for England. He would wind up as part of the the U.S.Army Air Forces. This was the forerunner of the Air Force, which would be created as a separate branch of the service in 1947.

Frank didn’t follow his brother into the Army. He became a Navy man on Aug. 20, 1942.

Both made it back from the war and returned to Lenoir-Rhyne athletics as seasoned, hardened veterans. Both starred for the Bears in football and baseball. Both racked up every conceivable accolade. Burton was a 27-year-old football captain for the Bears in 1946. Frank would captain the Bears in 1947. Both Bargers would earn induction into the Lenoir-Rhyne Hall of Fame.

Time had run out for Burton as far as his big league baseball dreams, but after graduating from Lenoir-Rhyne, he was playing Class D minor league baseball in Hickory in 1947. That’s when he was offered the AD and coaching jobs at Valdese High in Burke County. That meant coaching non-stop — football, baseball, girls and boys basketball and track. He accepted. He got married in the spring of 1948. He earned a masters from Appalachian State.

After a year at Mineral Springs High, near Winston-Salem, Frank was offered a great coaching gig. He was hired by Hickory in 1949 and would become a legend there as a coach and AD. His amazing tenure would last through 1985. He would coach championship teams in baseball, track and field, girls basketball, golf and football. His career coaching mark in football was 273-120-5. He was inducted into the North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame. Today, the Hickory Red Tornadoes play football in Frank Barger Stadium.

Burton had tremendous success coaching at Valdese, especially in football. His teams were 80-16-4. There was a time when he had 12 Valdese players active in college ball. He brought Valdese teams down to Rowan County to pound China Grove and Landis.

One of Burton’s claims to fame was Frank never beat him in football. Valdese and Hickory clashed once with a championship on the line. Valdese’s Doug Cline, who went on to play at Clemson and in the AFL, roared 75 yards on the first play, and that was that.

Burton eventually had a falling out with the folks at Valdese over money. The football program was bringing in dollars, but none of it was being spent on new equipment.

When North Rowan opened in 1958, the timing was right for a move. Burton was ready for the next challenge, and he came back home to Rowan County. Specifically, to Fourth Street in Spencer.

His first North Rowan team was 0-10. But the Cavaliers were turning things around by 1960 when they went 6-2-2. They were 9-1 in 1961, tying for the conference title, but Mooresville beat North head-to-head and got the berth in the WNCHSAA playoffs.

In 1962, North won its first outright conference football title. Burton was named the Post’s football coach of the year for the county in 1960 and 1962.

North Rowan’s football program started to slide some after that, but Burton had North track and field rolling. In that sport, the Cavs had blossomed into perennial conference champs. Barger and Walt Baker had constructed the school’s first hurdles in the North wood shop. Barger got his vaulters fiber glass poles before most schools had them.

In 1965, North enjoyed its biggest athletic breakthrough up to that point, taking the WNCHSAA track and field championship and beating schools such as Hickory, Shelby and A.L. Brown in the process.

In late April, 1966, the Post published the surprising story that Barger had turned in his letter of resignation, and it had been accepted by North Rowan. That story didn’t reveal Burton was heading to Davie County, but that was going to be his next stop. Jack Ward had wooed him.

North racked up another North Piedmont Conference championship that year and then added the Piedmont championship, a major meet in which all the NPC and South Piedmont Conference schools came together.

The WNCHSAA championship meet was scheduled for Shelby on Saturday, May 14. That morning, the father of Steve Ward, one of North Rowan’s runners, was killed in an accident. They were a man down.

That set the stage for an epic track and field confrontation in 1966, in what would be Burton Barger’s last meet at the helm of the Cavaliers.

North Rowan and Frank Barger’s Hickory team probably were co-favorites, but A.L. Brown also was considered a threat.

Only the top four placed in each event with a 5-3-2-1 scoring system. Running events were in yards, of course. N.C. meets were still more than a decade away from employing metric distances.

Hickory’s team was led by sprinter Mike Reinhardt, who had anchored 440 and 880 relay champions for the Red Tornadoes in previous years. Hickory also had Larry Jordan, the defending WNNHSAA champion in the 880-yard run and very strong relay teams.

Reinhardt won the 100, but Donnie Jones, one of the North’s first Black athletes, took third.

North got some help in the 220.

South Rowan’s Rodney Cress finished second to Reinhardt in the 100, but Cress won the 220. Albemarle’s Whit Morrow took second, knocking Reinhardt down to third. Alan Griggs took fourth for North.

Morrow won the 440. Jordan took the 880 for Hickory in a record time.

Terry Helms won the mile for the Wonders, while Gary Frye took the long jump.

North’s efforts for most of the day were carried by Ricky Leonard, who would win three individual events and be acknowledged as the meet’s top performer. Leonard was undefeated in the hurdles in 1966 and he once again claimed both events — the 180 low hurdles and the 120 high hurdles. He ran the low hurdles in 15 flat, a meet record. He also found time to win the high jump.

North got a big victory — five points — in the 440 relay. Freddy West, Jimmy Lyerly, Jones and Alan Griggs made up the winning relay team that nipped Hickory.

North accumulated more precious points from Bobby Hutchins (third in the high jump) and Hal Barnes (third in the low hurdles).

North experienced a potential disaster in the 880 relay. That relay unit actually crossed the line second behind Hickory and anchor man Reinhardt, but North was a DQ when an official ruled a Cavalier had bumped another runner.

North took a 26-22 lead to the last event — the mile relay — but it was still a long way from over. That was an event Hickory was almost certain to win, and that’s an event that Ward normally ran for North.

North needed at least third — two points — to clinch the meet.

The Cavaliers would get three. Griggs stepped in for Ward to run with Leonard, Cooter Shuping and Barnes. Hickory won the event, but North placed second and won the meet to complete and undefeated season. Burton Barger went out a winner with North Rowan track, edging his brother’s team.

The final: North 29, Hickory 27.

A.L. Brown finished third with 21 points.

South Rowan tied Albemarle for fourth place, thanks to the sprinting of Cress and third places from Larry Deal in the discus and Guy Shaver in the mile.

West Rowan finished sixth, with Billy Cranfield scoring all 11 points for the Falcons. Cranfield won with a meet-record pole vault and was second in the long jump and triple jump.

East Rowan had a second from Chip Earnhardt in the 400 and a third from John Fisher in the 880.

•••

Jones would win the 100 and North would make it a WNCHSAA three-peat in 1967 under new coach Ralph Shatterly.

Burton Barger would assist with Davie football for two seasons, but he would quickly turn his focus to track and field and started building another track power.

Burton complained in a long speech about Davie’s lack of track facilities when he first arrived, so he was instructed to limit his remarks to six words the next time he stepped to the podium.

He complied with that order. “Asphalt track, asphalt track, asphalt track,” he growled. Then he sat down.

His Davie teams would win WNCHSAA track titles in 1969, 1974, 1975 as well as the last WNCHSAA meet that was held in 1977. He also coached a couple of cross country champions.

He’s in the Davie Hall of Fame.

His son, Allen, would star in football for Davie, play in the Shrine Bowl and serve as captain of the Lenoir-Rhyne Bears.

Frank Barger would die in 1991. Burton Barger lived to be 92 and died in 2011. Both brothers coached in the Shrine Bowl.