By Mike London

mike.london@salisburypost.com

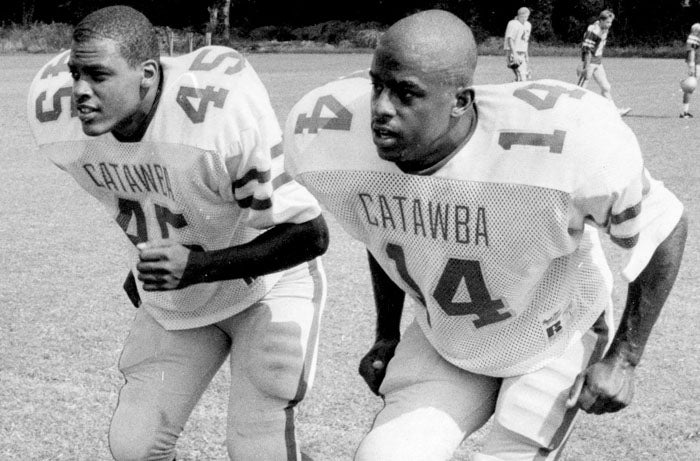

LEXINGTON, Ky. — When Curtis Walker first came to Catawba in 1988, he wasn’t a polished product.

Now the head coach of Catawba’s football team, Walker is remembered as the hard-hitting, fumble-forcing All-American and Hall of Famer he became in the early 1990s.

But in 1988 those glory days were still only dreams.

One of the athletes who helped Walker get through a redshirt year, that year of adjustment to college academics and college football competition, was defensive back Ray Daniels.

Daniels garnered national attention earlier this month as one of the two Black owners of a horse that galloped in the Kentucky Derby.

“Ray was one of the guys who took me under his wing right from the start,” Walker said. “We had a very good relationship and he gave me a lot of advice.”

Daniels was only a sophomore in 1988, but he seemed older and more mature than that, wise beyond his years. He’d seen more of the world than most of the Catawba Indians. Born in New York and a high school star in Atlanta, he possessed big-city savvy. He came to Catawba with a suitcase full of credentials. He’d been team MVP in football and he’s also been inducted into the National Honor Society.

“In 1988, he was already one of our leaders off the field,” Walker said. “And on the field, he was one of those guys that when he had something to say, you heard exactly what he said. You heard every word of what he said. He led at a high level.”

Daniels had been redshirted, as well, so he knew what that was all about. His redshirt season was 1986. Daniels had watched and learned from All-America free safety Keith Henry.

Daniels emerged from spring drills in 1987 with a reputation as one of the fastest men on the team and with a role as Catawba’s fifth DB. That meant he would be playing quite a bit as the top backup in the secondary in the fall.

Coaches believed his best position was free safety, but Henry had that spot locked down, so Daniels played mostly cornerback. Daniels played enough as a redshirt freshman to make 52 tackles.

There was an early November game in 1987 against Guilford in which Daniels stepped in front of a Guilford pitchout late in the first quarter and took it 74 yards for a touchdown. In the official stats, the play went in the books as a “fumble recovery,” and it is still the longest fumble return TD in program history.

That was a weird game. Catawba was leading 10-0 and Guilford was driving when Daniels made that play. It proved a backbreaker. Guilford coughed up 11 turnovers that day, and Catawba led 66-0 before Guilford finally scored. The outrageous final was 73-14.

As a sophomore in 1988, Daniels boosted his tackles total to 62, while mentoring Walker and other Catawba youngsters.

“There were some great conversations in his room,” Walker said. “Ray was knowledgeable not only about football, but a lot of things beyond football.”

In 1989, as a junior, Daniels was a full-time free safety. He made 109 tackles and two interceptions and was named first team All-South Atlantic Conference. He was second on the team in stops. Linebacker Rodney Goodine led with 111 tackles.

When his senior season began in 1990, Daniels was being touted as a potential All-America candidate. He also was headed for a place among the program’s all-time leaders in tackles.

He made 15 tackles in the third game of the 1990 season against Mars Hill, but then he went down for the season — and for his career — with a torn biceps muscle.

“I don’t remember what team we were playing, but I do remember the day it happened,” Walker said. “Ray was one of those guys who was very reluctant to leave the field even when he was hurt. Unfortunately, that injury turned out to be a lot more serious than anyone first thought.”

Daniels graduated with Bachelor of Arts degree in management from Catawba in 1991.

His teammates didn’t know what he’d do next, but no one doubted he’d be successful at whatever venture he attempted.

“We thought he might become an attorney or maybe he would go into politics,” Walker said. “He was a highly driven individual, a born leader.”

As it turned out, Daniels made his mark in the business world.

He began in 1992 as manager of a Waffle House. He moved up that chain steadily. Fifteen years later, he was senior vice president of operations, responsible for 105 stores, 3,500 employees, and more than $200 million in annual sales.

“Not a surprise,” Walker said. “Knowing the work ethic Ray had built, business success wasn’t a surprise.”

Daniels and Walker have always stayed in touch through the years through golf tournaments and alumni gatherings. The Walker family has visited the Daniels family in Kentucky. Daniels is married to a doctor and they have two children.

In 2008, Daniels purchased the Waffle House franchise for Lexington, Ky.

He owned 13 Waffle Houses when he sold the chain about a year ago so he could move on to other ventures.

Daniels, 52, serves on so many boards now that it would take some time to name them all. In 2019, he was selected to serve as a member of the Catawba Board of Trustees.

Horse racing is “the sport of kings” and requires exceptionally deep pockets to compete on the high end. Daniels got involved in the sport about three years ago. He experienced success as part-owner of a horse named Heavenly Hill.

Heavenly Hill was claimed for $16,000, earned $54,000, and then was sold for $100,000.

That profitable scenario encouraged Daniels to become part of the three-man syndicate that claimed a horse called Necker Island (named for an island in the Virgin Islands) back in June for $100,000. The horse had speedy bloodlines and a solid track record and it proved good enough to qualify for the Kentucky Derby.

The odds on Necker Island in the Derby were 50-to-1, and the horse finished ninth out of 15 entries, but it was a breakthrough moment for Daniels and Black partner Greg Harbut, whose family has been involved in the horse racing industry for generations. Harbut’s great-grandfather, Will Harbut, was a groom for legendary champion Man o’ War.

Daniels and Harbut were the first black owners of a Derby horse in 13 years. Their presence at Churchill Downs raised a lot of awareness for Black contributions to the sport, many of which have been forgotten or ignored.

In the first Kentucky Derby held in 1875, 13 of the 15 jockeys were Black and the inaugural Derby was won by Oliver Lewis, a Black jockey.

Fifteen of the first 28 Derby winners were Black in an era when Blacks not only rode the horses, but trained and groomed them.

By 1904, things had changed. Black riders were denied licenses and banned from Churchill Downs. They steadily disappeared from the sport, victims of legislation, segregation and intimidation.

In 1962, Harbut’s grandfather, Tom, was part owner of a horse (Touch Bar) that qualified to run in the 1962 Kentucky Derby. He still wasn’t allowed to sit in the grandstand to watch.

The Kentucky Derby is the pinnacle of the horse racing world, so the presence of Daniels and Harbut at the 2020 Derby made an important statement for inclusion and opportunity.

The 146th edition of the “Run for the Roses” is now in the books, but Daniels and Harbut promised in many interviews that the Derby was just the start. Their hope is to spawn ownership and syndicate groups throughout the country.

Walker communicated frequently with Daniels during Derby week, wishing him luck and offering a shoulder to lean on, just as Daniels provided for Catawba’s young football players decades ago.

“I’m not surprised at all that Ray found a way to get back into sports,” Walker said. “I just didn’t know it would be horse racing.”