High school track and field: Boyden made history 50 years ago

Published 12:00 am Sunday, August 29, 2021

By Mike London

mike.london@salisburypost.com

SALISBURY — Did local high school athletes ever win something bigger than a state championship?

Some men now in their late 60s, who were at Boyden High — soon to become Salisbury High — 50 years ago will tell you that they did.

Fifteen Boyden Hornets won the Duke-Durham Relays, a massive meet, the biggest track and field stage that the Southeastern USA had to offer. The meet was held on Saturday, April 17, 1971. There were only two classifications for that meet — schools with fewer than 1,000 students and schools with more than 1,000. Boyden was one of the 48 “small” schools.

Hosted by Duke University, the Relays attracted teams from North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia and Tennessee. There were 1,500 elite athletes assembled in Durham, representing 90 high schools and prep schools.

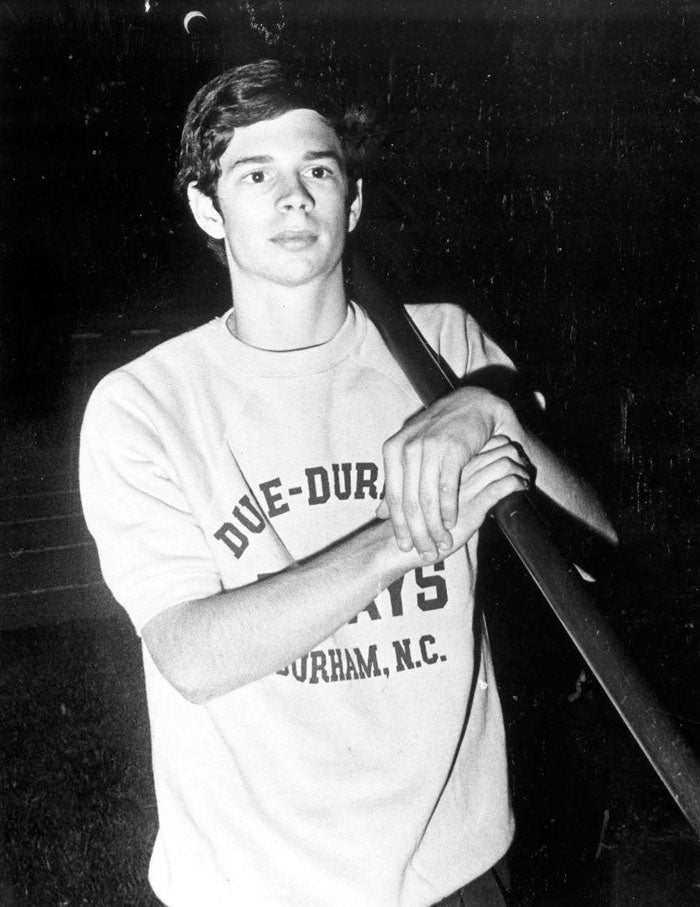

“It was the epitome of the high school sports adventure — at least as far as track and field goes,” remembers Charles Busby, a champion Boyden pole vaulter in 1971. “Our entry in the Duke-Durham Relays was a thoroughly improbable scheme, with little chance of success. Too many things had to go right, and almost everything could go wrong. Common sense said it couldn’t be done. No one in his right mind would have bet on it, but this is not a story about people in their right minds.”

Boyden’s victory was remarkable.

The circumstances bordered insanity, mostly because Boyden competed in the Charlotte Metro Relays on the Friday night before the Duke-Durham Relays. Boyden whipped Hickory and all but one of the huge Charlotte schools in that meet, but a Myers Park machine that would go on to win the NCHSAA’s 4A state championship, outscored Boyden 100-86.

Boyden athletes slept a few hours after that that rare and disappointing second-place finish. Then they convened, climbed into family vehicles and hit the road to Durham on Saturday morning. They arrived in time to warm up. The meet started at 10.

The Duke-Durham Relays never was on Boyden’s rigid schedule. Coaches, renowned for their good sense, never approved of the wild adventure.

April was when the track season got serious every year in the old Western North Carolina High School Activities Association. The Rowan County Championships were just a week away. The South Piedmont Conference Championships and the combined SPC-North Piedmont Conference Meet came right after that. Those were all qualifying tests that set the stage for the WNCHSAA Meet that capped the season. That’s where Boyden, North Rowan and A.L. Brown would tangle with the likes of Shelby.

In other words, April wasn’t a time when you were looking for another meet to squeeze into an already demanding schedule.

To understand Boyden’s victory of 50 years ago on a multi-state level, you have to start with 1966.

“That’s the year the ninth grade was moved from Boyden to Knox Junior High,” Busby explained. “An organized athletic program was instituted at Knox that replaced rec department football and YMCA-based basketball. The new structure changed the world of sports in Salisbury.”

One of the products of that move of ninth-graders was the birth of a Knox track program. Coaches Bill Cansler and Dale Basinger, with the support J.H. Knox, superintendent of the city schools created a monster program out of a field of weeds.

“Coach Cansler could make things happen,” Busby said. “He made an impact on the lives of a lot of young guys.”

Cansler knew how to slice through the red tape. He laid out a track, installed jumping pits and constructed hurdles.

“He instilled in a group of kids a love for track and field which had not previously existed, and which would carry forward to the next level,” Busby said. “He not only built a track program, but also an athletic program fostering relationships between the Black and white athletes at Knox that would continue at the high school.”

Race was part of the story. The Boyden guys who would win the Duke-Durham Relays were about an even mixture of Blacks and whites. Most of them would have their first interactions at Knox, which began a five-year string of unbeaten track and field seasons in 1967.

That would translate to great high school success under head coach Pete Stout at Boyden.

In 1970, Boyden took what would be the first of three straight WNCHSAA championships in track and field. Boyden’s star was Rogers Jackson, a gifted and competitive hurdler/sprinter/jumper, but there was a deep supporting cast of talented runners around him.

“Jackson was arguably the most gifted athlete of many during those years,” Busby said. “He was a born hurdler who brought his game every time he stepped on the track.”

The 1970 Boyden track team was loaded — and didn’t take much of a hit at graduation.

“When the 1971 season opened, our track team had a swagger that was hard to conceal,” Busby said. “We were running two and three deep with quality performers in almost every event. Point accumulations were either impressive or embarrassing, depending on which team you were on. Countless records were set.”

Boyden wanted to venture out, to seek stronger competition. The obvious venue for that was the Duke-Durham Relays.

“Boyden had not participated at Duke to any significant extent prior to 1971, but some individuals had made the trip,” Busby said. “Rogers Jackson’s brother, Bobby, had competed and had returned to Salisbury with a Duke-Durham Relays sweatshirt, which Rogers was allowed to wear on occasion. It was a real eye-catcher. We all wanted one and there was only one legitimate way to get one.”

The dream of competing in Durham gradually became a reality.

“The idea persisted and solidified,” Busby said. “Duke had just resurfaced its track, and it was better than anything Boyden had seen or ever would see. The Duke-Durham Relays represented the biggest stage any sports team at Boyden would ever have the chance to play on. If we were as good as we thought we were, there was just one way to prove it — win the Duke-Durham Relays.”

The idea of going to Duke was proposed to the coaches but was immediately dismissed. It couldn’t be done. The schedule was too tight. The risk of injury from overwork was too great.

But the biggest single issue was Boyden’s entry in the Metrolina Relays, hosted by East Mecklenburg, the night before Duke.

“Two major meets in less than 24 hours? That hardly seemed fair — or sane,” Busby said.

But first, Boyden had to figure out how to enter the meet in Durham. How does a team enter without coaches?

“We were proposing to fly directly in the face of prevailing authority, and that would require some improvising,” Busby said. “This is where the story went from improbable to crazy.”

But the time for talk was over. Someone had to take the bull by the horns.

Runner Coleman Ramsey (who would became a federal law enforcement officer) called the meet director at Duke. Ramsey identified himself as the assistant track coach at Boyden High School and explained that the team wanted to enter the meet.

“He bluffed his way through it in a convincing manner,” said Busby, who would become a lawyer. “Some paperwork was done, possibly bordering on forgery, and we were in. That was it. Mission accomplished.”

No coach and no bus, but they were going.

“Duke was on Saturday morning, while the meet in Charlotte on Friday was at night and it was a very long night. We stopped at Hardees for a snack and got back to Salisbury around midnight. Now all we had to do was drag ourselves out of bed on Saturday morning and get to Duke and get warmed up before the meet started. That sounds simple enough, but in the days of no cell phones, no email and 15 guys coming from all over Salisbury, the logistics were formidable. Still, by way of multiple vehicles and drivers, including the Busby family station wagon, everyone got collected and left Salisbury by 7 a.m. This feat may be the most impressive aspect of the whole adventure. Any plan which depends on getting 15 high school guys out of bed on Saturday morning, seems even more preposterous now than it did then. None of us one had ever been to Duke, but we found the track.”

Busby was in charge of figuring out Boyden’s entries — who would enter what events and who would run on the critical relay teams.

He’d attended the 1969 NCAA Track Championships at the University of Tennessee with his brother, Jim, and they had come away impressed by the “big meet strategy” – the idea that a big meet could be won by a small group of athletes, if they were strategically placed in the right races. In 1969, San Jose State had won the NCAA championship with a small number of athletes.

Less than half of the full Boyden team went to Durham, but Jackson, Aubrey Childers, Mike Partee, Terry Beattie, John Hanford, Dennis Brisson and Gary Powers were relay horses.

One horse who would have been there was missing. Ellis Alexander was in the process of winning a Morehead Scholarship and had to be elsewhere.

“Our horses just needed to be properly deployed and not overworked,” Busby said. “They had the speed and they had the power. Because of the schedule at Duke, the relay teams were reshuffled somewhat from prior meets to spread the load around. Childers and Beattie were top 100-yard dash men and normally would have been entered in the 100, but they were not. Those races involved preliminary heats, work which would have detracted from their performances in the relays. We placed our bets on the relays.”

Boyden had never competed in the medley relay — two 220-yard dashes, followed by a 440 and then an 880. Gonzolous Harrington, not normally a relay runner, was plugged into the medley to carry the long anchor leg, following Beattie, Childers and Brisson.

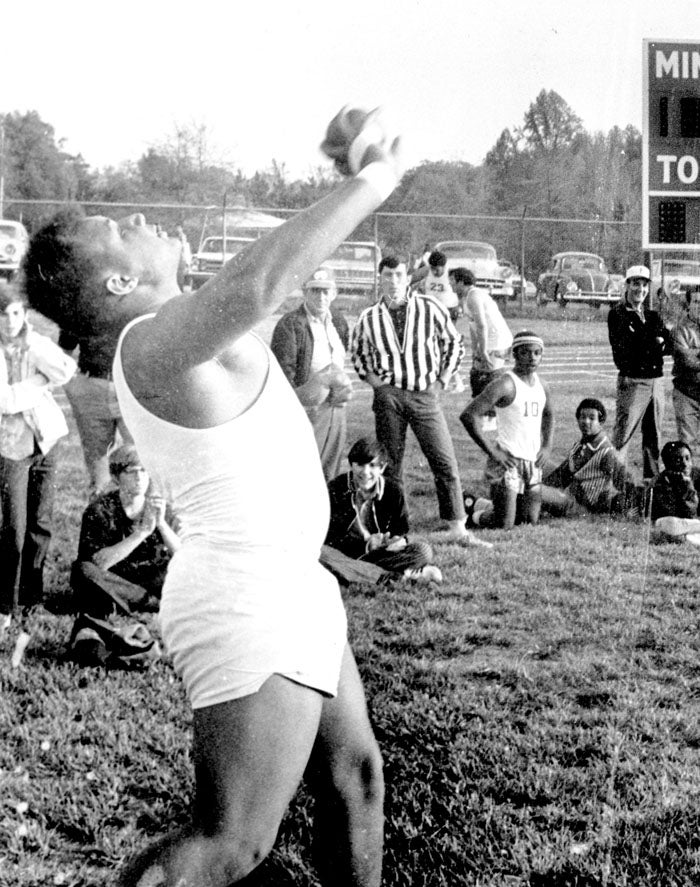

In the field events, Robert Pulliam (shot put and discus), Kenny Holt (high jump), Ricardo Kerns (long jump) and the Busby brothers (pole vault) were entered in their usual events.

Other than Ramsey in the mile, Jackson was the only team member to run an individual track event. He was entered in the high hurdles.

“Jackson was in a class by himself, and the thinking was that he was not only a good bet, he was a lock,” Busby said. “It would be his chance to shine.”

Points were awarded for the top five in each event, with an 8-6-4-3-2 scoring system. Hargrave Military Academy emerged as the main rival.

“Hargrave had an excellent track program, but, more significantly for us, one of Hargrave’s top runners was Rick Allesindrini,” Busby said. “Rick was from Salisbury, he had gone to school with many of us, and he never missed a chance to tell us that Hargrave could kick our butts anytime, anywhere.”

As the meet unfolded, it wasn’t business as usual. Accustomed to dominating everything, the Boyden team went from being concerned to the brink of discouragement because the wins weren’t piling up. The 440 relay (Partee, Brisson, Hanford, Childers) finished third – good, but not up to their standard. In the 880 relay (Jackson, Powers, Childers, Hanford), Hanford struggled home with a pulled muscle on the anchor leg to finish second in 1:31.9. Hargrave won that event, beating Boyden by 0.4 seconds. Allesindrini ran the third leg for Hargrave, adding salt to the wound.

Pulliam placed fourth and fifth in the shot and discus, events in which he was accustomed to first or second. Kerns set a school record in the long jump (21 feet, 5.5 inches), but that was only good for third place. Busby finished finished fourth in the pole vault. Holt added a fourth in the high jump.

Jackson won the small division hurdles, setting an electronically timed meet record (and school record) of 14.2 seconds.

“Jackson knew he was on the stage with the big boys, and he responded in a big way,” Busby said.

Jackson’s record was short-lived. It was broken later in the day by Charles Foster, who ran 13.8 in the large school division. Three years later, Foster, competing for North Carolina Central, was the No. 1-ranked hurdler in the world. He competed in the 1976 Olympic Games.

Boyden’s medley relay team of Childers, Beattie, Brisson and Harrington made the difference. They ran 3:40.5 and won in their debut in the event. Those points sealed Boyden’s victory.

In lengthening shadows at Wallace Wade Stadium, the guys from Salisbury finished with 41 points. That was enough. Hargrave placed second.

“It was only a fraction of the points we had grown accustomed to rolling up, but the plan had been executed to perfection by a group of guys who would not be denied,” Busby said.

The team received two trophies — one for winning its division and one from Governor Bob Scott for scoring the most points (tied with large school champ Dobyns-Bennett of Kingsport, Tenn.). The team also received and proudly wore Duke-Durham Relays sweatshirts and championship patches.

History tells us that Boyden (thankfully) came through that unauthorized quest in one piece and crushed its standard opponents the rest of the way, streaking to county, conference, bi-conference and WNCHSAA championships.

In the WNCHSAA Meet, Boyden, broke five meet records on the brand new track at Davie County and scored 124 points to blow away the field. Second-place Shelby scored 81.

Of the 15 Boyden athletes who traveled to the Duke-Durham Relays, 14 had competed in track for Knox. That’s where life-long bonds started forming.

“The 1971 track team was a close-knit group, able to rise above the problems of race and focus on getting it done,” Busby said. “That was a good season, by any measure.”

In June 1971, two months after the Duke-Durham Relays, Duke was the scene of the Pan Africa-USA International Track Meet. That was the largest track event held in the Western Hemisphere that year and the first international track meet ever held in the Southeast. It pitted some of America’s best, including Steve Prefontaine, against competitors from 14 nations. The two-day meet attracted 52,000 spectators and was a major triumph for Leroy Walker, the dynamic coach at Durham’s North Carolina Central University who had dreamed of bringing Africa to the South.