‘We’re meeting needs everyday’: Volunteer-based Good Shepherd’s Clinic treats underserved population

Published 12:05 am Thursday, December 23, 2021

- Jean Allen sorts through medical information on her computer at Good Shepherd's Clinic. Ben Stansell/Salisbury Post

SALISBURY — When Jean Allen opened the metal door to Good Shepherd’s Clinic two weeks ago, she was expecting a much-needed easy work day.

The clinic, which typically treats almost two dozen patients each Tuesday, had an unusually light appointment schedule.

“We thought, ‘Oh, this is going to be nice,’” said Allen, the clinic’s executive director. “We needed a break.”

The break never came.

One of the patients who visited that night had missed her past three appointments, which would usually have resulted in the clinic no longer offering her services. Instead of immediately discharging her, Allen asked why she had been a no show.

“She started crying,” Allen said.

Without enough money for gas, the patient couldn’t drive her blind, diabetic husband to dialysis. He went into septic shock and was hospitalized. The patient, a diabetic herself, hadn’t eaten for four days. To make the situation worse, her brother and mother had died from COVID-19 back in her home country of Mexico.

“She was completely distraught,” Allen said.

The volunteers staffing the clinic that night quickly mobilized. Some gathered around to calm the patient down with words of prayer and encouragement while others made a trip to Aldi to purchase two week’s worth of groceries for her.

“We went into overdrive,” Allen said. “But all of us experienced Christmas that night because we understood what it was like to have nothing and to give yourself away to someone else who is in need.”

The volunteers at Good Shepherd’s Clinic experience Christmas on an almost weekly basis. The clinic, located at the rear of the “old YMCA” building on North Fulton Street, provides free healthcare services to indigent people of Rowan County without insurance. Oftentimes, patients are undocumented and come to Good Shepherd’s when they have no other options and are in bad shape.

“We’re treating patients that could drop dead in front of us,” Allen said.

The faith-based clinic was founded in 1993 by members of First Baptist Church’s congregation and other interested parties. The clinic set up shop in the former YMCA building purchased by the church to house several ministries, inhabiting space in the back of the structure previously home to racquetball courts and locker rooms.

The goal of the clinic was to provide treatment to people who weren’t having their medical needs met elsewhere.

“We were concerned about the people falling through the cracks, that didn’t qualify for insurance, didn’t qualify for social services, didn’t qualify for medicaid,” Allen said.

An example during that time, she said, was a young single mother working hard to care for her children who couldn’t afford an insurance premium and therefore couldn’t routinely visit the doctor.

“She’s going to push herself to work no matter whether she’s feeling well or not because she can’t afford to go to the doctor or to the (emergency room) until one day she passes out and they have to take her to the ER.” Allen said. “Then she has a hospital bill she can’t pay.”

The idea was to provide patients, particularly those dealing with diabetes or hypertension, with a managed care program that would allow them to control their condition and prevent hospital visits.

Over time, the demographics served by the clinic shifted. As the population of undocumented immigrants increased in Rowan County, Hispanic people who couldn’t get care at the hospital or at doctors’ offices began to rely on the Good Shepherd’s services.

That has remained the case. Of the 71 patients who visited the clinic in 2021, 66 of them were Hispanic or Latino. The other five were either Black or white. Those patients, all of them impoverished, made 478 total visits to the clinic. Those numbers don’t include the patients the clinic served via tele-health or the patients who received mammograms at the clinic during a special event in September. With those patients added in, Allen said, the clinic has served hundreds of individuals over the past year.

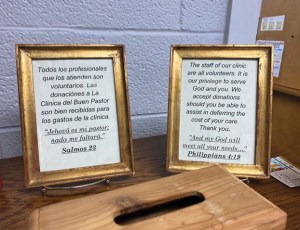

The clinic has helped patients from 29 different countries, including every country from Central America. That’s why most of the signs hanging in the clinic are duplicated in Spanish. It’s also why Allen uses a rotating group of about six translators, most of whom are fluent in Spanish.

The faith-based clinic serves indigent patients in Rowan County, most of whom are Hispanic or Latino. Ben Stansell/Salisbury Post

Even with a translator, the language barrier can sometimes be a hurdle.

One time, a doctor who was attempting to examine a patient’s finger grew frustrated because the patient kept showing him their foot.

“I died laughing and I said, ‘It’s because they don’t have a word for toes in Spanish,” Allen said.

The barrier is almost always possible to overcome with a little patience and effort.

In addition to the interpreters, the clinic is staffed by two registered nurses, one retired missionary and Allen’s husband, Gary. There are about 12 rotating physicians, including a physical therapist and four optometrists, with various focus areas. Dr. Yuthapong Sukkasem, a family medicine specialist for Novant Health, is the clinic’s medical director.

“To have him is a miracle,” Allen said.

Ron Hollified leads the clinic’s nursing staff. Steve Fuller, a licensed pharmacist, is the director of pharmacy. Mark Brittain is the director of the eye clinic and John Kesler is the lead dentist.

All of the clinic’s staff are volunteers besides Allen, who receives a small salary.

The clinic opens for scheduled appointments every Tuesday. Most of the patients seen on that day, Allen said, have severe diabetes and need medication or to make lifestyle changes. Patients are typically offered fresh fruit, dinner and sometimes pre-packaged dry meals to take home.

“We’re meeting needs everyday right where we are,” Allen said.

Before the pandemic, patients could come with family members. To reduce the number of people in the building, the clinic now only allows the person being treated to enter. The clinic also cut back on dental services, but Allen said she would like to change that in 2022.

As patients wait to be seen by a doctor, a bible study is held in the waiting area. Patients aren’t forced to participate, Allen said, but the clinic doesn’t hide the fact that it’s faith-based. Allen attributes the clinic’s success to God.

“It’s Jesus,” Allen said. “He’s the one who does it. He moves the people and encourages them to do it.”

While the doctors are only at the clinic on Tuesdays, Allen and the pharmacy team return each Wednesday to fill prescriptions. On Thursday, Allen, a nurse and an interpreter return to dispense medicine to patients.

The work doesn’t stop there. Allen and a team of volunteers, some of them church members, continuously call to check in on patients to ensure that they’re feeling well, taking their prescribed medication and sticking to their care management plan.

Allen believes the clinic is doing what it was established to do almost three decades ago.

“We are saving the community probably $1.5 to $1.7 million every year by our patients not having to show up at the emergency room,” Allen said. “Those costs are going to be exorbitant because they’re critical care, not continual care like we give and they’re just going to be a revolving door, they’re going to come back.”

Good Shepherd’s Clinic does it all on a tight $60,000 budget, most of which is consumed by having to buy medication. The funding comes almost entirely from private donations.

The clinic is always in need of monetary donations, but Allen said food donations are also of particular interest since the clinic likes to provide its volunteers with a meal. Those interested in helping Good Shepherd’s Clinic can call 704-636-7200. The phone isn’t always monitored, but Allen attempts to reply to people who leave their name and number.