Former nurse Yvonne Dixon of Salisbury helping close racial gap in healthcare

Published 12:00 am Sunday, February 12, 2023

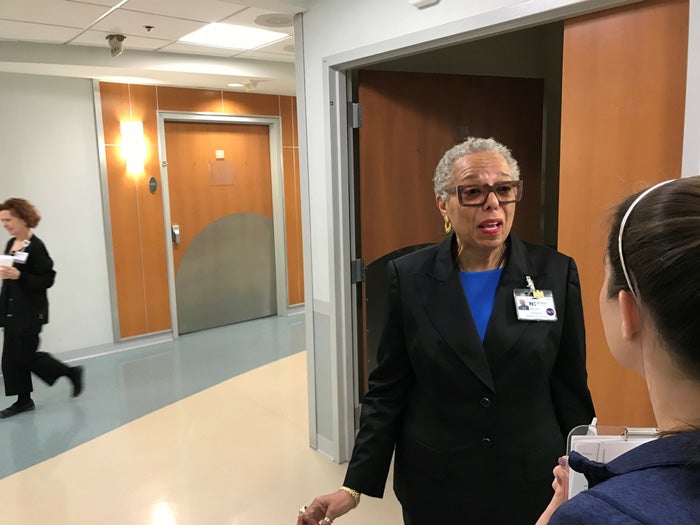

- Yvonne Dixon — Novant Health photo

By Yoona Ha

Novant Health’s Healthy Headlines

Yvonne Dixon still vividly recalls the heartbreak and hard work of her family’s struggle to care for her great-grandmother in Salisbury in the 1970s.

Caring for a person with dementia is often too much for a family to handle on their own. But her parents had limited means and there were no other options available.

“Even watching and observing how much it took to care for the sick and elderly built toxic stress in me as a child,” said Dixon. Today, Dixon is a leader in Diversity & Inclusion at Novant Health, and her memories of those times inform her work to deliver the best care possible to communities.

Dixon’s story is a profound part of the African-American experience. In the U.S., discrimination and poverty often meant black families had to handle their own problems with no support from government or other institutions that were available to whites.

Dr. Rita Hargrave, a clinical instructor in the department of psychiatry at University of California, Davis, points out that African-American families assumed such caregiver roles due to a historic lack of access black families have to quality care and financial and public support. All of the above can make caregiving, especially for patients with dementia, a “great emotional burden,” she said.

After graduating high school in Salisbury, Dixon worked stitching men’s suits in a sewing factory until the day her supervisor stood behind her on the factory floor and threatened to document her output because she wasn’t producing fast enough. She never returned. Then another opportunity fell into her lap. What about working in a long-term assisted care facility?

‘I learned a lesson’

Though Dixon was skeptical at first, she gave it a try and found herself loving the time she spent with patients from different backgrounds.

“I learned a lesson on how to look for beauty in someone that’s not skin deep, but rather in the heart and in the stories of their life,” Dixon said. It gave her exposure to a wide variety of older patients, all of whom made her rethink her stereotypes of the elderly.

Dixon went on to get her nursing degree and became a nurse in Winston-Salem. There’s one shift in particular that still stands out today. A supervisor stopped her from seeing a patient because the patient didn’t want a black person providing his treatment.

“That patient in room 703 was the Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan,” Dixon said. The supervisor found a white nurse.

Taking care of everybody

It was a defining moment in Dixon’s life, and one that opened her young eyes to the challenge of providing health care to a diverse and complex world. Eventually, she would come to the conclusion that the words “equal” and “equity” can mean very different things when it comes to making sure patients get the care they deserve.

In a system that’s equal, people are treated the same and are provided the same resources. But in health care, equality doesn’t always solve the problems that communities face. As Dixon pointed out, a health care facility can be open and available for everyone. But some people may lack the resources to get there, or afford treatment or medication. Under these circumstances, “equal” services have still created an inequity of care.

As the World Health Organization puts it, health equity is about creating an environment in which everyone has equal opportunities to live their healthiest lives. The obligation for Novant Health, Dixon said, is to make sure “our most vulnerable community members have access to benefit from our care.”

Moreover, she added, “What we have to say to our patients is that whatever cultural beliefs or background you have, we’re going to acknowledge it and respect it.” In the instance of the KKK patient, she said, that meant finding a white nurse and moving on.

Asking lots of questions

Dixon eventually ended up working in diversity and inclusion in health care and was a part of several successful initiatives to achieve equity. She facilitated the opening of the first medical oncology center in Sumter, South Carolina that hired more providers from differing cultural and linguistic backgrounds to serve the diverse patient population.

“That community needed more culturally competent providers who could overcome the barriers and mistrust that some have toward traditional health care systems,” Dixon said. “They called our practice, ‘The United Nations.’ ”

Diversity is key when it comes to delivering health care in the United States. One study that looked at black men, the group with the lowest life expectancy in the U.S., found that having doctors of the same race improved patient-provider communication and reduced the mortality rates.

Today, Dixon is the director of health equity at Novant Health, where she works to identify the gaps in health care by understanding which rural, low-income and racial and ethnic minorities need access and how Novant Health can develop programs that can help close those gaps. When COVID arrived, she took on the challenge of vaccine hesitancy in the Black community. Through her role, she is constantly listening, discussing, planning and implementing health equity initiatives that can build relationships and improve health disparities among vulnerable populations.

One example: Dixon worked on a project to reduce avoidable readmissions among African-American patients. In 2018, Novant Health was named as the first health care system to receive the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Health Equity Award for closing the gap in readmission rates by 50 percent among black patients with pneumonia.

“Having genuine curiosity and trying to understand someone on their own terms can go a really long way,” Dixon said. “You only find out what’s missing by asking questions and we’re working to find better ways for our providers to listen to you and make you view your health as something that you want to have a conversation with us about.”