Heritage Day: Erwin Middle teacher shares enslaved ancestor’s personal account of life in bondage

Published 12:01 am Thursday, February 23, 2023

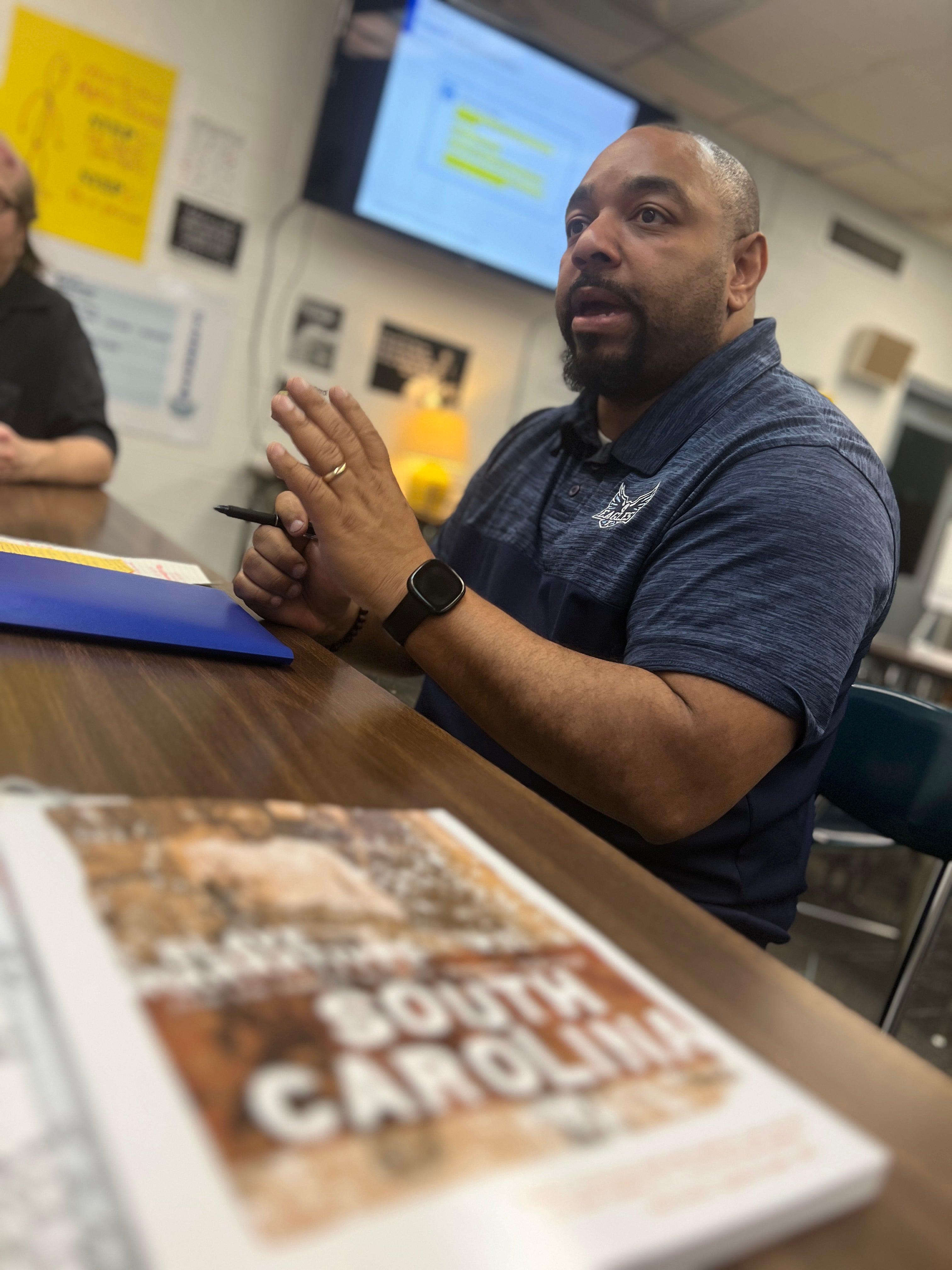

- Erwin Middle School seventh grade math teacher Carlton Jackson recently learned his family's ancestry could be traced to a slave plantation in South Carolina. - Submitted

SALISBURY — Connecting material with students can be one of the most complex parts of teaching, but a recent discovery in Erwin Middle School math teacher Carlton Jackson’s family gave him a relatable way to tell an important story.

Seventh graders at Erwin have spent the year focusing on the Inclusive portion of its Eagle PRIDE (Prepared, Respectful, Inclusive, Disciplined, Engaged) expectations with monthly cultural-heritage celebrations.

February’s celebration proved personal for Jackson, who learned last year that he was directly descended from an enslaved person named Millie Barber, who lived on a plantation in Winnsboro, South Carolina.

“Back in September, my sister mentioned that some interesting things were happening in our family,” Jackson said. “Some relatives’ research led them back to our great-great-grandmother’s life on a plantation. I thought it was just a random conversation or hearsay, but there is a book.”

The book is “Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers Project (1936-1938).” Commissioned to capture first-hand experiences of those who personally endured slavery, the project captured thousands of ex-enslaved people’s accounts of life on the plantation. By the time of the project, Jackson’s great-great-grandmother was in her 80s.

The interview was recorded and then transcribed for the book.

“These are her actual words,” Jackson said. “I tried not to be too emotional. It was painful yet joyful. In reading it, what I found, I would assume, if I was in this situation, I know that we today are quick to anger about what took place back then, but when I think about how she interviewed, she didn’t seem angry about it.

“She even mentioned that there were good times and hard times. She talked about rejoicing and going to the Promised Land. She spoke highly, which was odd to me, of her relationship with her owners and how they took care of her.”

Even after earning her freedom, a lack of opportunity pushed Barber back into a life not unlike slave conditions as a subsistence farmer, a fate that found many such freed men and women.

Sharing his great-great-grandmother’s story with his students was important to Jackson because he felt like he was sharing his own story.

“Reading her interview and seeing the type of person that she was, her values were then passed on to all my other relatives,” Jackson said. “I see her in my grandmother. I see her in my mother, and I see her in me. To me, that is one of the things that I left the kids with. This is me.”

The way it resonated with some of his students proved it was also important to them.

“It’s hard to think, wow, this was not that many years ago,” seventh grader Gabby Polnisch said. “Kids read textbooks and say, ‘Oh, we have already learned about this. I’m not really going to pay attention.’ But when your teacher says, ‘I’m related to this person,’ it changes it.”

The first-hand account from a teacher’s relative broke the mold that Polnisch indicated she had become accustomed to.

“Kids learn about slavery every other year in school,” Polnisch said. “It becomes the norm, and it’s like I have heard this multiple times. When you’re sitting there, and someone is physically telling you I am related to someone, here is what they have been thorough, here is the proof, it feels more interesting.”

Jackson shared Barber’s unabridged interview with his students. Most of her accounts of life on a plantation were from her childhood. Learning how slavery impacted children stuck out to Manuela Robles-Munoz.

“It makes me feel sad because kids didn’t have a choice,” Robles-Munoz said. “They couldn’t say I don’t want to or I can’t. Whatever condition they were under, they had to work. They couldn’t really have a childhood because they were working all the time.”

To have been born into a life outside her control got a reaction from fellow seventh grader Riley Kunonga.

“It is really unfair,” Kunonga said. “Some kids could have had asthma or something, and that would be really hard for them because they have no choice.”

What also bothered Kunonga was just how recently it happened.

“When you think about it, if it wasn’t that far back,” Kunonga said.

Presenting that kind of material is not always easily digestible, but Jackson doesn’t sugarcoat things.

“When I look at some of the things that students have to deal with, I want to encourage them to be able to face it,” Jackson said. “I want to encourage them to be able to know right from wrong and to reason with these decisions of how we talk to others, how we view others and how we include others.”

As for the heritage celebrations, Jackson and his colleague Amanda Fear, who teaches seventh grade English and language arts, are determined to make their students more wholesome.

“One of the things we deal with, even today, not to the magnitude that it was back then, but one thing we look at is relationships with other folks,” Jackson said. “We are all different. We all have different cultural backgrounds.

“We have to learn to understand others and respect others, and that is difficult. Even adults have challenges with looking at those differences and being able to take it on.”

Fear added, “(Jackson) and I connected last year because I had some observations I made about the community, and I needed some support. We were talking about intersections. We initially wanted to start a multicultural club that didn’t come about, but it manifested as these celebrations.”

Like her colleague, teaching acceptance and celebrating diversity is more than just crucial to Fear. It’s personal.

“I am biracial,” Fear said. “My mother is an immigrant from Southeast Asia. My father is from Flint, Michigan. My ex-husband is biracial. He’s half-black. Being the spouse of a Black man was very interesting. I was treated and talked to in a specific way when we were out and about.

“My daughter, Sophia, has to deal with perceptions about her because of her skin color. She is white, Asian and Black. My mother always passed down the idea of acceptance and love. We need to take care of each other.”

Given her experiences, talking about difficult subjects is not off the table for Fear.

“We can’t take care of each other if we don’t communicate,” Fear said. “You don’t communicate if you don’t understand the words you are using. You have to use words that everyone understands.”

Fear acknowledges that regional and cultural norms vary.

“The best way I learned to communicate is direct,” Fear said. “This is what I mean, and I mean it the way that I say. In the South, it can come across as harsh and uncaring, but I teach that way because I care. I want to cultivate and foster a world where my children will be taken care of by society and also take care of others. That is my main goal. I feel like it is not fair to our students to avoid tough topics. They are true. They are there. We are all human, and that is what (Jackson) and I always try to impress upon whoever we come in contact with. We are all human beings. We deserve validation and to be cared for.”

The heritage celebrations will continue next month as Erwin Middle students delve into Irish culture.