Wayne Hinshaw: First digital camera wasn’t a keeper

Published 12:00 am Saturday, June 18, 2016

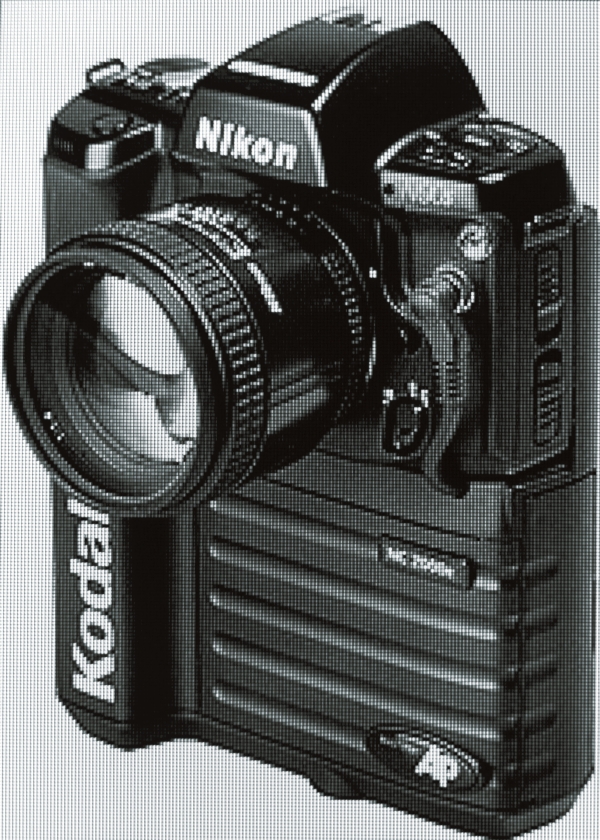

- The Kodak NC2000

Folks, gather around and pull up a chair. I’m going to tell you a story about the “Covered Wagon Days,” the Wild West days of the development of Kodak’s very first commercial digital camera for photojournalists and the small role the Salisbury Post played in that development.

Our fairy tale starts way back in ancient times in the year of 1994. Some of you will remember that year, and others of you were not even born.

The newsgathering organization that we know as the Associated Press had the idea that they would provide the design, give advice and funding to Kodak if they would develop a “filmless” camera and manufacture it for newsgathering. AP would market the camera and sell it to their newspaper members.

Neither AP nor Kodak had a camera body to use for this new creation so they used a Nikon N90S film camera body for the adventure. The camera had a strange look like stacked blocks. The Nikon N90S camera sat on top of what looked like two other boxes of electronics. It was big, heavy, bulky and awkward to hold in your hands. The camera was named the Kodak NC2000. The NC was short for “News Camera.” I’m sure that was AP’s idea.

In 1994, the camera sold for about $18,000. Remember that $18,000 in 1994 would be more like $28,000 or $29,000 today.

The Salisbury Post was a member of the AP, so we were potential customers to purchase the NC2000. AP devised a “rent-to-buy” plan for smaller newspapers like us. My memory is that publisher Jim Hurley agreed to enter the plan to the tune of $200 per month. The contract said that we could pay for the camera monthly, or we could return the camera to AP at any time. The camera was “cutting edge” technology, and we wanted to be a part of the project. The Post had long been a leader in the newspaper publishing field.

When the camera arrived, it was 7 inches to 8 inches tall, weighing in around 4 pounds. It was an ugly beauty, if you know what I mean. It was like a young kid with “cow licks” in his ugly hair sticking straight up, but he is a beautiful child anyway.

I was so excited to see and hold the future of photojournalism in my hands. I could go on assignments, and no one would have ever seen such a camera before. It was experimental. Wow, it was cool.

Our photo staff in 1994 was Jim Barringer, Jayson Singe and myself. Jim didn’t want anything to do with the ugly duckling camera. Jayson, who was a recent UNC-Chapel Hill graduate at the time and on top of all the latest technology, tried it out, curled up his nose and handed it back to me.

It was an awful camera. You just didn’t know what the camera was going to do. It had no LCD screen on the back like modern-day digital cameras, so you couldn’t see what it was doing. You could shoot two frames per second, but after six shots, two at a time, it would pause for a buffer period of around five seconds so that it could write the images to the card.

It had a self contained a NiCad battery that had to be plugged into an electrical outlet for charging. If your battery died out in the field, you were finished for the day. It was nearly impossible to get the flash to sync with the camera. Everyone’s light skin tone color was a rosy red like a bad sunburn. If you photographed a house fire, the flames were usually purple. Sometimes your photos had one side of the image very yellow and the other end very blue. Both were unpredictable to deal with.

You would do the best you could with your photos, then hope and pray that you had something that the newspaper could use. You learned to think, “Just give me my film camera back.”

I once shot a water line leak on Salisbury Avenue in Spencer with the NC2000. In my photo, the water was running down the street in the sunlight. Each bright area of highlight in the water created a red and blue moire pattern of lines. The water leak looked like a stream of “Christmas lights” running down the street.

That was the last assignment that I photographed using the NC2000 camera. It was shipped back to the AP after 2 months of trial in the field and $400 cost for the experiment.

The camera was a disappointment, but I felt good about the test, knowing that it was the first step in developing a digital camera that was the wave of the future for photojournalists in the coming years.