Patrick Gannon: Finding common ground

Published 12:00 am Wednesday, July 13, 2016

RALEIGH — On a recent Thursday, three African-American members of the N.C. General Assembly held a press conference to draw attention to recent shootings of black men by police.

They talked in the aftermath of the shooting deaths of Philando Castile near St. Paul, Minn., and Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, La. Both shootings were caught on video and disseminated widely. Both shootings, at least on the surface, seem questionable and perhaps unnecessary.

The frustration of the three lawmakers was palpable. Rep. Rodney Moore, a Charlotte Democrat, described the “two incidents in 48 hours, which are basically business as usual for the African-American community as it relates to interaction with law enforcement.”

Rep. Yvonne Holley, a Raleigh Democrat, contrasted America’s “culture of policing” with soldiers at war in other countries. Soldiers are more cautious in war zones, she suggested.

“In America, it’s looked at as we’ve got to stop something. Something’s going on, and my job is to stop it,” Holley said. “Not necessarily, let me see what’s happening, what’s going on first.”

The press conference received relatively little attention from the media and other elected officials.

Later that day, five police officers in Dallas, Texas, were gunned down by a lone black suspect, who targeted them because they were cops and because they were white. The police shootings and the shootings of police officers have sparked sometimes-tense protests about relations between African-Americans and law enforcement.

As with any major societal problem, there isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution, but ignoring the issue won’t make it go away.

In the days following the Dallas shootings, police chiefs and other leaders have said they believe there are too many guns on the streets, that police officers should be paid more, that police departments should rid themselves of the 1 or 2 percent of “bad cops” and that officers should do more to try to gain the respect of the people they serve. (Of course, respect is a two-way street, and officers who do that should expect similar treatment in return.)

David Brown, the Dallas police chief, has said he believes officers are being asked to do too much, putting them under greater strain. They encounter the mentally ill every day and must deal with that because of a lack of funding elsewhere. In Dallas, he said, police are asked to chase loose dogs.

Brown was quoted in The Washington Post as saying that officers were frustrated with what police officers are being forced to do “while lawmakers do not seek possible solutions to the country’s violence.”

Back in North Carolina, Moore filed a bill in 2015 that would have required officers to receive annual education and training about discriminatory profiling and authorized powerful citizen review boards to investigate allegations of police misconduct. The review boards are particularly controversial, and the bill was never heard in a committee.

“Be on the lookout for this bill to come out in 2017 and for it to have even more provisions in it that will try to look at conversations and safeguards, not only for the public, but for the police,” Moore said at the news conference.

If nothing else, that could be a starting point for meaningful public discourse about solutions.

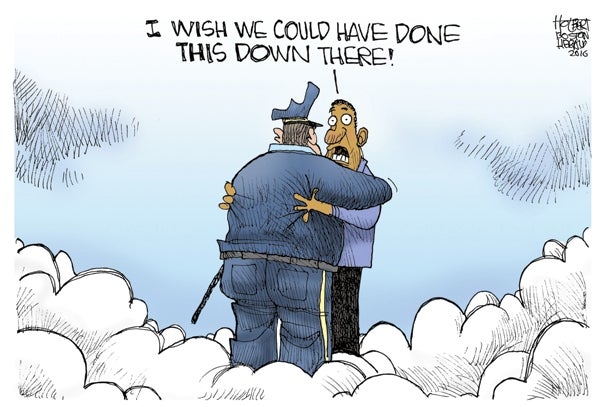

Rep. Garland Pierce, a Wagram Democrat, said the intent of the news conference was not to vilify police.

“Everybody’s got to work together, all citizens, to ensure safe neighborhoods for everybody,” he said.

“I want policemen to go home at night because they have families. I want the other person to go home. Everybody has families.”

Patrick Gannon is the columnist for the Capitol Press Association. Reach him at pgannon@ncinsider.com.