In its heyday, Boyden House had a central role in Salisbury social life

Published 12:10 am Sunday, September 11, 2016

Editor’s note: The Empire Hotel in downtown Salisbury, now under contract for purchase, started out as The Boyden House and has had many different incarnations. This is part of a series about the hotel’s rich history.

By Betty Dan Spencer

Special to the Salisbury Post

The Civil War officially ended and by May 1865, Salisbury was occupied by federal soldiers. A new struggle — Reconstruction — began on the home front. Salisbury was no exception to other Southern cities that had to rebuild and deal with loss of property and income. The citizens had to adjust emotionally and deal with daily life under new terms.

After managing the Boyden House for 15 years, the proprietor, Thomas Howerton, disheartened over the war and the death of his wife, retired. The hotel business was physically demanding, and he was 70 years old. His son, Dr. William H. Howerton, obviously decided it was more lucrative to seek a living as a merchant than as a physician or hotelier and did not renew his lease on the Boyden House.

Although personal property had been left untouched during Stoneman’s Raid, business concerns did not fare as well. The office and print shop of the local newspaper, Carolina Watchman, was ransacked, all its type broken and thrown into the street. Nine months later, J.J. Bruner, editor and owner, began publishing the paper again on Jan. 8, 1866.

In this first issue, Calvin Scott Brown announced he had leased the late Boyden House and was reopening it as Brown’s Hotel. He said: “I am now having it thoroughly repaired, determined that it shall be second to no Hotel in North Carolina. With seven years experience as a Hotel manager, I feel confident that I can give entire satisfaction, all that I ask is a call. My table will be supplied with the best provisions that this market will afford, besides Oysters, Fish and Game, from Norfolk, Newbern and Wilmington, whenever to be procured.”

He also advertised other amenities such as The Bar, boasting that it was the finest and best stocked in North Carolina and would be open all hours of the day and night! In the same edition of the Watchman, in a second ad, he announced that the bar would be called the Gem Saloon, He listed the following concoctions to assuage one’s thirst: “Hot Spiced Rum, Old Irish Whiskey, Milk Punch, Hot Tom and Jerry, Hot Whiskey Skin,Hot Apple Toddy, Old Bourbon Whiskey, Brandy Smash, Scotch Whiskey, Jamaica Rum, Blackberry Brandy, Champagne, French Brandy, Madeira, Oporto Port and Sherry Wine, Edinburg and Philadelphia Ale, Brown Stout &c.” In connection with the hotel was a livery stable, where carriages, hacks, buggies and horses could be obtained, or horses boarded. Brown also added a billiard saloon, a novelty for Salisbury, and noted it would be fitted up in a few days with one of Phelan’s best tables.

Apparently the name Brown’s Hotel did not catch on with everyone. Even the newspapers vacillated between referring to the hotel by the new name or continuing to call it the Boyden House.

Calvin Scott Brown

Calvin Scott Brown, the proprietor, was a local boy which gave him a decided advantage. From a wealthy and prestigious family, he was a son of merchant Michael Brown and Isabella Maria Long, and the great-grandson of Michael Braun, who built the Old Stone House. All his life he had resided in downtown Salisbury. He and his father were in business together, operating the mercantile company of M. Brown and Son (located on the Square where Timeless Wig Shop is today).

In 1855 they dissolved their partnership. Young Brown moved to Morganton and took over the management of the recently built Walton House. He also held the mail contract between Salisbury and Asheville. The dispatches were transported via the Western N.C. Railroad to Morganton, and from that point to Asheville on Brown’s own stagecoach line. A natural entrepreneur like his father, he also ran a combination blacksmith-wagon repair shop, and a business which made boots, shoes, and harness. At the time North Carolina entered the Confederacy, Brown was 33 years old. He closed his business operations and joined the Bethel Regiment (later the 11th). He served as 1st lieutenant in Company G, Burke’s Rifles, and later as captain in Company D.

Escaping the ravages of fire

During Reconstruction, fire, the work of incendiaries, was a constant worry and threat to businesses. The Greensboro Patriot of March 3, 1866, reported that a fire, supposedly the work of an incendiary, occurred in Salisbury on Sunday night, Feb. 25. The article said that it destroyed “nearly a square, including the Banner and Watchman office. It broke out in the Tin shop of Mr. Baker, east of Brown’s Hotel, which is but little injured, and extended to the corner and up the cross street.” Once again the hotel, because it was a brick building, escaped the ravages of fire. The Daily Banner said they were in a novel predicament. “We sit in our office (writing now) surrounded by the debris of what was once the proud old Watchman office, but alas, Stoneman and the late fire has shorn it of its former beauty. The press is going in our front, a carpenter is malling, hammering, and sawing on our right, erecting stands; there is a man on the roof thumping away on tin, as he intended to make it secure against bad weather. It is simply ‘the music of labor.’ ”

The Watchman wrote that they “craved the indulgence of the subscribers for a week or two, while we are repairing damage done to our office by a sudden, and necessarily violent removal of it to get out of the way of fire.” The following week, Bruner wrote: “We may be under necessity of issuing our paper in half-sheet [two pages instead of four] a little longer than we expected. We have rather slender means left for rebuilding an establishment twice demolished, but perseverance overcomes all obstacles. … Surely it is not asking too much to request all who are indebted to the proprietor of this printing office for job work, &c., both on old and new accounts, to call and pay him. Our damage was serious, and cannot be repaired, except at a very heavy cost of tedious labor and several hundred dollars in cash.”

Confederate Military Prison Site

On Nov. 1, 1866, a significant auction was held at the Boyden House. Thomas P. Johnston, representing the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, sold at auction what was known as the “Prison Lot,” which consisted of lots 35, 36, 43, part of 44 (present-day block bounded by Long, Fisher, Shaver and Bank streets) in the South Square of Salisbury and 15 or 16 acres thereabouts. Brothers Moses L. and Reuben J. Holmes were the high bidders for $1,600. They held the land for a number of years before they registered the deed on March 3, 1882.

Distinguished visitors

On April 16, 1866, the Salisbury Banner noted that the Honorable Philo White and wife, formerly Mary Ann Hampton, of Salisbury, were occupying rooms at Brown’s Hotel and were receiving calls from their numerous friends. A few days later the Watchman described the dinner party given by C. S. Brown to honor the Whites. He served a 28-pound rock fish to the guests and during dinner “the intrinsic merits of the Rock” were “leisurely and satisfactorily discussed.” The newspaper also added: “The Boyden House, under the excellent management of Mr. Brown, is daily gaining popularity.”

Philo White

Philo White, a native of Whitestown, N.Y., came to Salisbury in 1820 and established a newspaper, the Western Carolinian, which he edited and owned for 10 years. He married a local lady, Nancy R. Hampton, and they were the parents of two children. Their daughter Mary, who died after being married only two months, was the first wife of John Willis Ellis, who later became governor of North Carolina. Ellis died in office on July 7, 1861. Since his death occurred during wartime, the Whites could not attend his funeral. While in Salisbury they visited Ellis’ gravesite in Davidson County. They were concerned that Ellis was buried in the family cemetery located on land since sold to strangers and had not been laid to rest beside his wife and their daughter Mary in the Old English Cemetery.

On May 4, 1866, the Watchman disclosed: “Profiting by the counsel and acquiescence of the Hon. PHILO WHITE and LADY, who are on a visit to their relations in this town and county, the family and friends of the deceased Governor, on Monday evening last effected a removal of his remains to a sepulture in the Salisbury Cemetery (best known as the English Grave Yard), where, we understand, it is intended to erect a suitable memorial in honor of this eminent statesman and pure patriot.”

Eight years later, an 11-foot marble monument, made in Whitestown, N.Y., by Allyn & Co., arrived in Salisbury where it was mounted on a granite base in the Old English Cemetery. Inscribed on one face of the marker is: “Erected as an affectionate memento of the many virtues and noble attributes of the late Gov. John W. Ellis: by Mr. and Mrs. Philo White, 1874.”

Maj. General Robert F. Hoke

The Salisbury Banner reported on Dec. 24, 1866: “Personal.—We had the pleasure of meeting at the Boyden House last evening Maj. General Hoke, late of the Confederate Army. The General wears his laurels so bravely won, with becoming dignity and modesty. He was looking well, and his pleasant face and noble bearing reminded us of happier yet more romantic days—When the South buoyant with hope, though cursed with all horrors of a desolating war, looked forward to the bright and happy future. So much can not be said now. Even in time of profound peace, she has no peace, no future, because of the malignity of her insatiate enemies.”

There is no mention of why Hoke was in Salisbury. Perhaps he came to visit Archibald Henderson Boyden, son of Nathaniel Boyden, owner of the hotel. Young “Baldy” Boyden, who volunteered in the Confederate Army when he was 16 years old, had served as Hoke’s personal courier during the war.

Gens. Clingman and Hill

At the same time, Gen. Thomas Lanier Clingman was also in Salisbury. In peacetime, he was a propagandist for the development of western N. C. In the 1850s, he had a running dispute with Dr. Elisha Mitchell about which was the highest mountain east of the Mississippi. Ultimately the highest peak was named Mount Mitchell and the second highest, Clingman’s Dome. Dr. Mitchell had Salisbury connections as his daughter Ellen Hannah was married to Dr. J. J. Summerell and lived on the corner of Fulton and Bank streets.

In May 1868 C.S. Brown entertained for Gen. D.H. Hill, who was a guest at the Boyden House.

Robert E. Lee

It had been written that Gen. Robert E. Lee ate breakfast at the Boyden Hotel on Wednesday, March 30, 1870, but he actually dined at Brown’s Eating House near the train depot. Under the heading “Distinguished Arrival,” this article was in The Old North State of April 1: “Quite a number of our citizens had the pleasure, on Wednesday morning, of meeting at Brown’s Eating House, with Gen. Robert E. Lee. He is going further South for his health; one of his daughters accompanies him. They only tarried for breakfast, accepting the kind hospitalities of mine host, Brown.”

1867: A new amenity

Even though the occupation of Salisbury ended in May 1867, and the federal soldiers left town, life was still not back to normal. Money was tight and merchants were struggling to buy inventory and keep their doors open. A curious ad for a new amenity at the Boyden House appeared in the Old North State:

BATH ROOM.

A Plunge Bath, Hip Bath and Shower Bath at any hour of the day or night.

Hot, Warm or Cold. Call at the Boyden House.

A reporter for the Weekly Progress of Raleigh visited Rowan County and complimented the Boyden House in its issue of May 2: “One of the finest hotels in the whole county and most probably the very best in the state is now kept here by C. S. Brown. The indifferent keeping of hotels for many years at this place may cause this statement to fall on incredulous ears. It is unvarnished truth however.”

Apparently Brown, in spite of hard times, was making a success of the hotel he had leased. The Boyden House almost had a fire on Saturday, May 18. Brown had a large awning which he intended to hoist in front of the hotel. He had it thoroughly saturated with oil, folded up and laid away in the storeroom. Getting up early, Brown smelled fumes and found the odor was coming from the awning. His discovery was most timely because the cloth had not burst into flames, but it was badly scorched.

On May 29, the Watchman proclaimed: “Our little town was taken rather by surprise last Monday morning by the announcement that Judge Kelley, of Mobile notoriety, was stopping at the Boyden House, and would probably address the people during the day.” Kelley was a Radical, a faction of politicians within the Republican Party who opposed slavery during the war, distrusted ex-Confederates, and emphasized equality and voting rights for “freedmen.” He made his speech at Town Hall and was introduced by Nathaniel Boyden.

The Watchman acknowledged that Kelley “acquitted himself better than we expected he could do under the circumstances,” especially since the editor thought it was anomalous for “orators of other States to come among us, unsolicited, to make political harangues to the people. … We are glad he said ‘reconstruction, in good faith, would ensure the admittance of our representatives to Congress if they could take the oath’ because we suppose that to be the end of the vexed question of reconstruction.”

Tragedy strikes

On Wednesday, Sept. 3, 1869, “ a negro boy named Nat, a servant at the Boyden House, was shot in the forehead and instantly killed. The newspaper account was confusing, reporting that “the killing seems to have been the result of the accidental discharge of a pistol,” and also calling it a homicide.

The Old North State of Friday, Nov. 10, 1871, disclosed that John Scott fell from the third story of the Boyden House and was killed. Scott served in Company E, 5th N.C. Regiment, during the war and was wounded at Gettysburg. He was born Aug. 15, 1820, in Ayrshire, Scotland, died Nov. 9, 1871, and is buried in the Old English Cemetery. He was survived by his wife, Helen Murdoch Scott, sister of William Murdoch of Salisbury.

New ownership

Nathaniel Boyden, owner of the Boyden House, died on Nov. 20, 1873. To his son, John Augustus Boyden, he willed “my brick-hotel, with all the furniture therein and everything connected therewith belonging to me, including the front and back lots.”

Musical chairs

After eight years as proprietor of the Boyden House, C.S. Brown sold his hotel furniture and left Salisbury in February 1874, moving to Raleigh to run the National Hotel in that city.

Like the game of musical chairs, the management of the Boyden House was constantly rotating. William Rowzee (later spelled Rouzer) was the first to rent the Boyden House after Brown left. He, along with other proprietors in town, banded together and all charged the same amount: $25 per month for room and board, or $18 for a seat at the table, alone. Claud E. Mills of Baltimore came to help him manage the hotel. In October Rowzee and Mills denied the rumor that the hotel was changing hands, but apparently there was more substance to hearsay than they were willing to admit.

At the beginning of 1875, W.T. Linton, who had been managing the National Hotel in Salisbury, leased the Boyden House for $1,800 a year. He quickly purchased new furniture, ordered a custom-made hotel desk, and acquired Queensware china for the dining hall. He celebrated the reopening of the hotel with a fancy dress ball and extended invitations to guests in all parts of North Carolina. By July Linton had tired of running the hotel and announced his intention to pursue other interests.

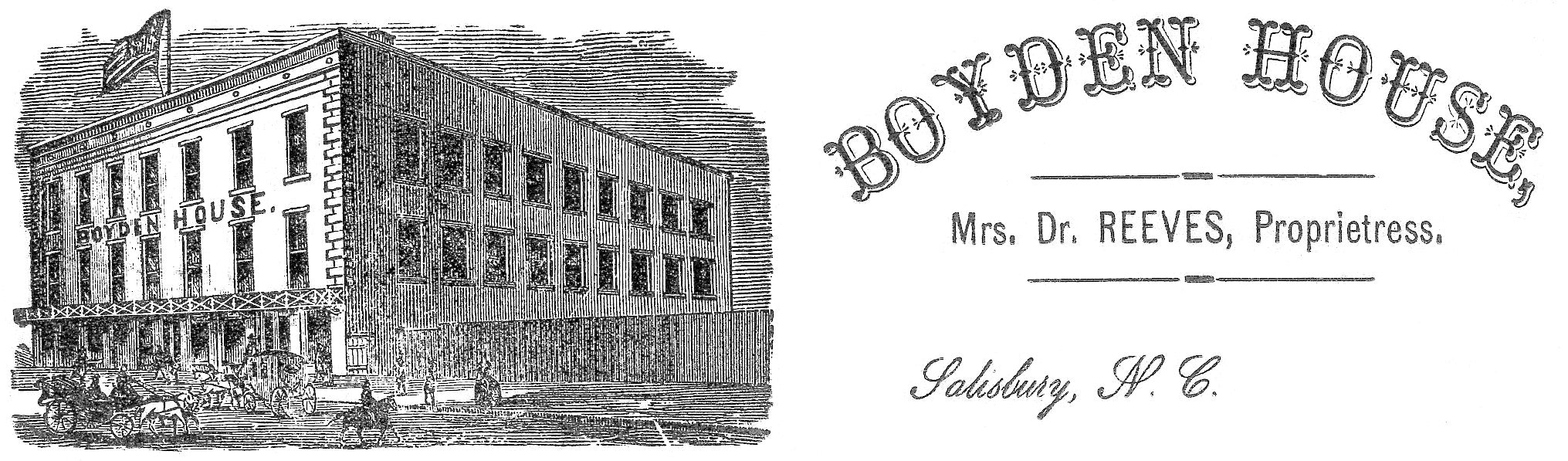

Once again the hotel changed management — this time it was put in the hands of a lady, Mrs. Margaret Ann Brown Reeves, widow of Dr. Samuel Reeves. She had followed Linton as manager of the National Hotel. The Watchman promoted her and wrote that she “has hitherto been remarkably successful in Hotel business, and with the advantages secured in the Boyden, is better prepared than ever before to display her skill in this line.”

John A. Boyden, who had recently inherited the hotel from his father Nathaniel, decided to update the façade with a “new, substantial and elegant front” which “will make the Boyden one of the most imposing hotel building in the South.” When this was accomplished Mrs. Reeves had stationery imprinted, and this is the first known image of the Boyden House, then 20 years old.

By January 1878, the hotel was once again under the supervision of Calvin Scott Brown. Leaving the National Hotel in Raleigh, he returned to Salisbury and took over the lease of the Boyden House.