Dear Mr. Peeler: Cheerwine’s old boss saved war letters from his homesick employees

Published 12:10 am Sunday, January 29, 2017

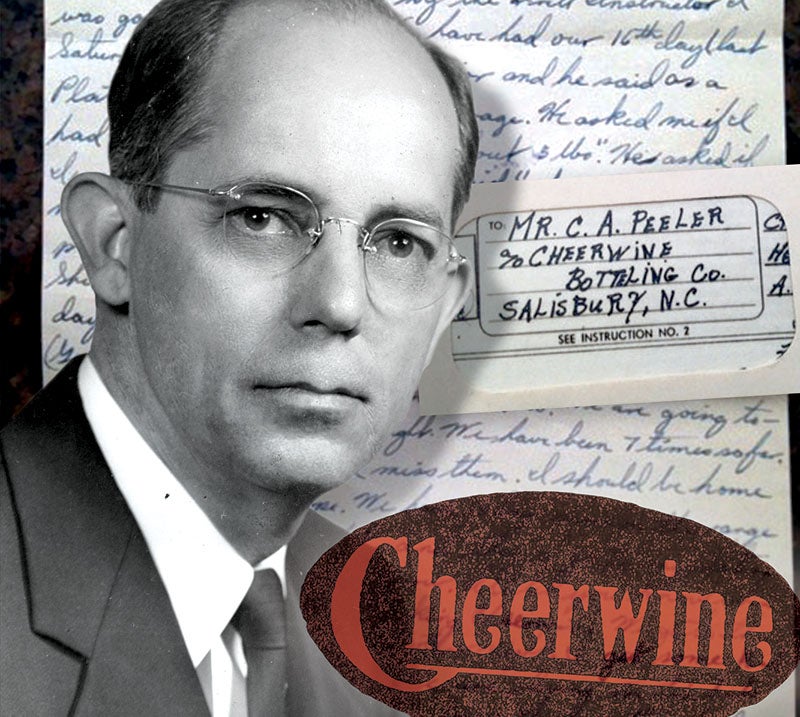

- Photos courtesy of Cheerwine, Celia Jarrett and Salisbury Post archives. Graphic by Andy Mooney / Salisbury Post Employees of Cheerwine who were off at war during World War II sometimes wrote home to Clifford A. Peeler, the head of the company. Usually, they simply addressed their letter to Peeler in care of Cheerwine Bottling in Salisbury.

SALISBURY — Having recently arrived in Calcutta, India, during World War II, John C. Marley dashed off a letter to his old boss at Cheerwine in Salisbury, Clifford A. Peeler.

“I’m a long way from drinking any Cheerwine right now, but hope you are still selling all you can make,” Marley wrote on Nov. 7, 1944. “A good cold one would sure go good right now.”

Additional letters from other soldiers who had worked for Cheerwine arrived for Peeler during the war, often because he had written to them first. Almost every letter mentioned something about the Salisbury soft drink or the people at the plant on East Council Street they had left behind.

“Tell everyone hello and I miss them,” wrote Pvt. Francis B. “Frank” Barger, who was training to be a U.S. Marine at Parris Island.

It was Oct. 11, 1942, and the 18-year-old Barger told Peeler he was getting ready to head for church and hoped to catch a movie that night. He still faced at least 15 days on the shooting range and a week of K.P. before possibly coming home briefly, then shipping out.

“I miss drinking Cheerwine,” Barger wrote.

At the top of his Oct. 10, 1944, letter, Charles W. Nail scrawled in cursive, “Somewhere in Germany.”

“How does this find everyone at the plant?” Nail asked Peeler. “… Tell all the fellas hello, and I still think of them and hope to be back with them soon. I’d like to hear from y’all there once in a while.”

Two of the late Clifford A. Peeler’s grandchildren, Celia Jarrett and her brother Cliff Ritchie, recently happened across a handful of these World War II letters. Ritchie had been going through some cabinets at his house, which used to be his grandfather’s residence, and among some books left behind by Peeler was an envelope.

It contained papers, news clippings and the World War II letters, which captivated Jarrett. She wondered why her grandfather, who died in 2000 at the age of 96, had saved these particular letters.

They are now part of a yearlong exhibit of Cheerwine artifacts and history opening at the Rowan Museum between 1 and 4 p.m. today.

Jarrett noticed, for example, two letters more than three years apart from the young Marine Barger. In the second letter, dated Nov. 4, 1945, Barger was writing from Tsingtao, China, having arrived there after a stint in Okinawa, Japan.

Barger talked of being on an LST that listed to its port side on one trip and almost sank. He also wrote about his ship’s just being missed by Japanese suicide planes.

“One came so close you could have touched it with a 10-foot pole,” Barger told Peeler. “Everyone’s heart skipped a beat or stopped. I bet I aged 10 years when I saw it.

“But there were eight of my pals I know who didn’t see April 2 or V-J Day. They were swell guys.”

Peeler also had saved a letter from his brother-in-law Dr. Walter L. Tatum Sr. Owing to his long service in the Army reserves, Tatum was stationed at the time in England with the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Tatum’s letter from Feb. 5, 1944, was brief. He thanked Peeler with his help related to travel checks.

“This is a beautiful section of England,” Tatum continued. “Really get homesick when I see some of the names here.”

Tatum told Peeler he had received his Civitan Christmas card just before leaving the States and asked his brother-in-law to thank the club members for him. Both Tatum and Peeler were devoted Civitans. Tatum already had served as a district governor.

At his death in 2000, the 96-year-old Peeler was the longest serving member of anyone else in Civitan International.

Beside running Cheerwine and overseeing the Yadkin Hotel for decades, Peeler had been a Salisbury mayor and councilman, a school board chairman, a longtime Catawba College trustee and a First Union Bank director for more than half a century.

Except for Tatum, who began his letter “Dear Clifford,” the Cheerwine employees at war usually began their missives with “Dear Mr. Peeler” or “Dear Sir.”

When they addressed their envelopes, all the men had to write was “C.A. Peeler” or “Clifford A. Peeler” and mark it in care of Cheerwine Bottling in Salisbury, N.C. The letters found their way to the Cheerwine boss.

“How is everyone at the plant?” Barger asked in 1945, not long after the war was over. “Tell Joe Brady, Luke, Bob, Snider, Collins and all ‘Hello.’ Sure miss the good old Cheerwine. My mother sent me a couple bottles. It really hit the spot.”

Barger said on his first night in China he and some other Marines went to a restaurant “and got the works: T-bone steak, fried potatoes, sliced tomatoes, ice cream and apple pie.”

After he had another steak, more potatoes and milk, Barger said his bill was $3,000.

Knowing he probably had Peeler’s attention by then, Barger explained the American dollar was worth $2,000 in Chinese currency and had gone as high as one American dollar’s being equivalent to $4,300 in Chinese money.

Things were cheap. Barger said he hoped to be out of China by Dec. 1 and out of the service by March 1, 1946.

“Everyone is talking about what they’re going to do,” Barger said. “I’ve often wondered!!!!”

Note all the exclamation points.

Three years earlier, when he had been a Marine in training at Parris Island, Barger acknowledged, “It’s tough here, but I can take it, so far.”

Nail, fighting somewhere in Germany, told Peeler he had passed through France and Belgium “so fast I hardly seen it.” It had been snowing for two days, and Nail said the mud was knee deep.

“I see these big bombers go over, day and night,” Nail said, “and our big guns shake the windows where we stay.”

For the time being, he and some other soldiers were hunkered down in a house in a German town.

“I’ll say so long for now for the candle is getting low,” Nail wrote, signing off.

Marley, who had recently arrived in India, said he had gained four pounds since leaving the States, and he encouraged the always slim Peeler to travel to India to put on some weight.

“This is a real pretty country,’ Marley said. “I’m glad I have a chance to see it.”

Dr. Tatum, Peeler’s brother-in law, was well-known in Salisbury and much older as servicemen went.

Tatum had been elected Rowan County coroner in 1930 and remained in that position until entering the service March 1, 1941. For a short period in 1931, Tatum served as acting sheriff after the shooting death of Rowan County Sheriff Locke McKenzie.

As a physician, he rose to become chief of staff at Rowan Memorial Hospital.

Tatum was devoted to soldiering. As a young man, he had served briefly in World War I. During peacetime between the wars, he rose to the rank of major in the Army reserve and also was president of the Piedmont Chapter of the N.C. Reserve Officers Association.

In World War II, he served for a time in Alaska, when it was feared the Japanese might try to invade that territory. He directed field hospitals along the Alcan Highway, sections of which were still being built.

His family was able to stay with him for a time at Camp Grant in Illinois. In early 1944, he was sent to England, then onto the continent after the Allied invasion.

Tatum was stationed in Paris and Versailles. A July 5, 1945, letter to his family said he was leaving for conquered Berlin and expressed hope he would be home by Christmas.

Tatum never made it. On his way back from Berlin to Versailles, he stopped in Kassel, where he developed terrible pains in his head on a Sunday night. By Monday morning, he was taken to a field hospital, and on Tuesday, a plane flew him to the general hospital in Frankfurt, where he died Aug. 1, 1945, of a cerebral hemorrhage at age 46.

Tatum was buried in a military cemetery at Saint Avold, France.

The following March, his son, Walter Jr., accepted the Bronze Star his father was awarded posthumously. Walter Sr. also had received a Gratitude Medal and the Medal of Honor from the French government.

His death shocked his hometown and Clifford Peeler, for sure. It makes sense Peeler held onto one of Tatum’s war letters. He knew life’s nothing to take for granted.

Contact Mark Wineka at 704-797-4263, or mark.wineka@salisburypost.com.