How was western North Carolina won? Credit the trains

Published 12:10 am Saturday, February 25, 2017

By Mark Wineka

mark.wineka@salisburypost.com

SPENCER — The era of change arrived for Asheville and the rest of western North Carolina when the first train roared into the small burg of 4,000 people in October 1880.

It immediately opened the region to the timber industry, mining, tourism and, with all those things, political corruption. But just to build the rail lines into the mountains meant figuring out how to go up and down the steepest of grades and resorting to approaches such as loops, tunnels and shelves along the rivers.

Kevin Cherry, deputy secretary for the N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, described the accomplishments as marvels of engineering, construction and human spirit.

“I don’t think we can underestimate the importance of the Western North Carolina Railroad to the development of the state,” Cherry said Friday as the N.C. Transportation Museum opened a yearlong exhibit called “How the West Was Won: Trains and the Transformation of Western North Carolina.”

The building phase also was one of great danger and human sacrifice, with the deaths of roughly 120 people attributed to the mountain railroad construction.

The traveling exhibit is on loan from Mars Hill University’s Rural Heritage Museum. “How the West Was Won” is located in the last five bays of the Roundhouse and is part of visitors’ regular admission price to the transportation museum.

With that first train from Salisbury to Asheville in 1880, “the world of western North Carolina was transformed,” said former state Rep. Ray Rapp, who served as curator for the exhibit.

Prior to its unveiling Friday evening at the transportation museum in Spencer, the exhibit had been at the college’s Rural Heritage Museum, in Marion, at the depot in Saluda, S.C., and at the Mountain Heritage Museum.

Over time, more than 10,000 people have seen “How the West Was Won,” and those numbers will multiply now that it has reached Spencer, Rapp predicted.

The exhibit incorporates photos, videos, narratives and artifacts such as a rare smoke hood, an authentic Pullman porter jacket and bag and common tools used during the construction.

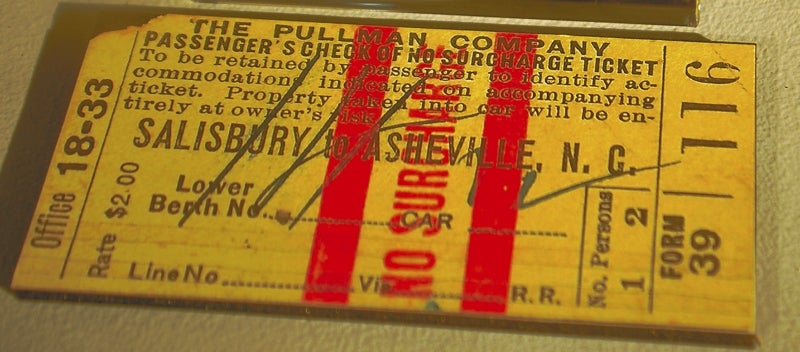

Visitors also will see items such as rail lanterns, a railroad pocket watch, locomotive bell, depot signs from stops along the western North Carolina route, a Salisbury-to-Asheville train ticket and other Pullman sleeper car items such as soaps, a towel and ticket punch.

Just beyond the main exhibit area, the museum has complementary stock from its own collection, including the No. 1925 Shay steam locomotive.

The Shay locomotive belonged to the Graham County Railroad and was used to haul logs out of the Snowbird Mountains. Also on display with the exhibit is the No. 1048 Carolina, Clinchfield & Ohio Caboose, which operated in the N.C. mountains for the CC&O and, later, the Clinchfield Railroad.

Rail enthusiasts know landmarks on the way to Asheville such as the Old Fort and Clinchfield loops and the steepest mainline railroad grade in the country on Saluda Mountain.

In his brief remarks, Rapp explained how investors drove the building of the rail lines toward Asheville from Salisbury, Saluda and eastern Tennessee and how some of the things that happened with the railroad’s arrival in the mountains weren’t necessarily good.

Asheville more than doubled its size in 10 years. Lumber barons denuded the mountains, which also were scarred from the miners looking for iron ore, feldspar, mica, barite and copper.

Beyond the timber and mining industries taking hold, so did tourism. George Vanderbilt and his mother first came to Asheville in 1887, and they were among visitors who were flooding toward new health spas.

With the tourism, mountain towns such as Saluda, Hendersonville, Hot Springs, Waynesville and Black Mountain flourished. Asheville also adopted as its slogan the title of the 1876 book by Salisbury author Christian Reid: “The Land of the Sky.”

The building of the railroad in western North Carolina was part of the story of Reconstruction between 1866 and 1877. Much of the labor used was convict labor and arguably an extension of slavery, Rapp said.

African-American men at the time were often arrested on the slimmest of charges, such as vagrancy, and sent to work on chain gangs, building infrastructure across the state.

“That’s the sad part of the story,” Rapp said, noting the largest percentage of the men who died building the rail lines into Asheville were African-Americans.

A more heartening chapter resulting from blacks working for the railroad came from their employment as Pullman porters. These kinds of railroad jobs led to the first establishment of a black middle class in the state and country.

Pullman porters made respectable wages, though they worked as much as 400 hours a month, Rural Heritage Museum Director Les Reker said. The 1950s Pullman jacket on display in the exhibit belonged to Tolbert Haynes Sr. of Asheville.

Both Reker and Cherry also praised the exhibit’s inclusion of a smoke hood. Cherry said only a few exist, and this one is on loan to the exhibit from the Gene Lail collection.

Made of canvas, metal and glass, the hood includes goggles and an hose used to provide clean air. Engineers of steam locomotives donned the hoods when they entered the long mountain tunnels to protect them against the smoke and gases.

“It was toxic air inside the tunnels,” Reker said.

Rapp said the railroads’ arrival in the N.C. mountains ended up shaping the region’s history, culture, economy “and all our lives in the country.”

Back in 1883, the country had 100 time zones between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Because this led to scheduling nightmares, the railroads joined forces to establish today’s four time zones, which were not actually codified by the federal government until 1918.

Rapp serves as chairman of the Western North Carolina Rail Corridor Committee, which has been working to re-establish of rail passenger service between Salisbury and Asheville.

Contact Mark Wineka at 704-797-4263.