Get sucked into the vortex of H.P. Lovecraft

Published 12:00 am Sunday, March 5, 2017

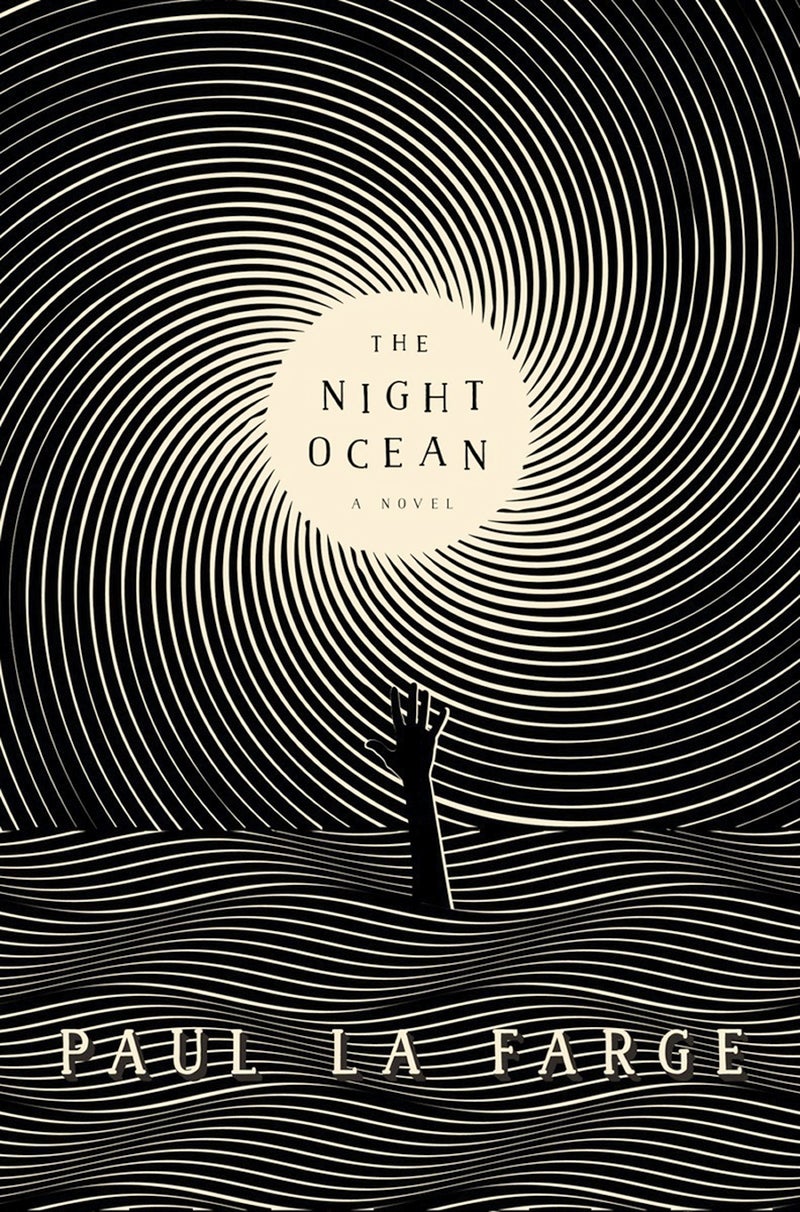

- The Night Ocean

“The Night Ocean,” by Paul La Farge. Penguin. 389 pp. $27.

By Jon Michaud

Special To The Washington Post

Though this year marks the 80th anniversary of H.P. Lovecraft’s death, the purveyor of baroque dread and menace remains very much alive in the imaginations of a host of American novelists.

Last year, Victor LaValle published “The Ballad of Black Tom,” a reworking of Lovecraft’s “The Horror at Red Hook.” Other novels include Matt Ruff’s “Lovecraft Country” and Peter Cannon’s “The Lovecraft Chronicles.”

Now comes “The Night Ocean,” by Paul La Farge, a booby-trapped doozy of a book that’s as challenging and confounding as one of the many-tentacled alien beings in Lovecraft’s Cthulhu mythos.

“The Night Ocean” begins simply and promisingly enough with a mystery. Our narrator is Marina Willett, a psychiatrist, whose husband, Charlie, has escaped from a mental hospital in Massachusetts, apparently to drown himself in a nearby lake.

Charlie was a journalist and a grade-A nerd. He collected “Star Wars” action figures, played Dungeons & Dragons, and, yes, admired the writings of H.P. Lovecraft.

Charlie’s trouble began when he came across the (true) story of Robert Barlow, Lovecraft’s literary executor. As a young fan, Barlow had struck up a correspondence with the author and, in the summer of 1934, Lovecraft (then in his 40s) spent two months visiting with the 16-year-old Barlow in Florida.

At this point — barely 30 pages into the novel — things get a lot more complicated.

Charlie had interviewed Barlow, written a book about him and become something of a literary celebrity until members of the Lovecraft community began questioning the accuracy of his reporting. The unraveling of his story sent Charlie to the mental hospital, and that, in turn, is the starting point for Marina’s investigation of her husband’s descent into madness.

The result is a novel composed of narratives and counternarratives, texts and subtexts. It is both homage to and a sendup of Lovecraft and the 19th-century Gothic fantasies that inspired him. The layering is dizzying.

Within Marina’s account lies Charlie’s account of Barlow’s retelling of his relationship with Lovecraft. Within Charlie’s story there are further sources: diaries, letters, recordings, transcripts — some of them red herrings and hoaxes and others seemingly true.

La Farge, who adorns his book with cameos from William S. Burroughs, Isaac Asimov, Edward R. Murrow and others, carries it all off with breathtaking skill and panache.

Because many of the characters in “The Night Ocean” are writers and editors, they frequently analyze and examine the stories that are told in the book. The result — somewhat frustratingly for a reviewer — is that La Farge has written a self-critiquing novel that seems to anticipate every possible complaint a reader could have.

Such cleverness is in evidence throughout, along with a wicked sense of humor. For example, all of the sex acts described in Lovecraft’s purported diary, the “Erotonomicon,” are named after creatures from his fiction, which results in sentences such as this: “Perform’d 3 times tonight ye YOGGE-SOTHOTHE.”

As entertaining as the novel is, its complex structure results almost inevitably in the lack of a true center. I couldn’t decide who the main protagonists were: Lovecraft and Barlow? Charlie and Marina? Or the troubled fan who published the “Erotonomicon.” His life story turns out to be the most moving in the book. The fact that it may not be entirely true doesn’t diminish its power.

Indeed, the vexed question of truth, so much in the news these days, is central to “The Night Ocean.” Among the legion of Lovecraft fans, there will doubtless be some who will painstakingly parse out the warp of facts from the weft of lies in this novel. Early on, I did my best to keep track, but soon I came to understand that it didn’t matter — that I was falling into La Farge’s trap, the same trap that drives Charlie mad. Above all else, “The Night Ocean” is about the transformational uses to which stories can be put. “This is how transmigration works,” one character notes. “Words take you over and you inhabit others in the form of words.”

It’s worth noting that Charlie Willett’s name is derived from two characters in Lovecraft’s long story “The Case of Charles Dexter Ward.” As Marina observes, that tale, about a man who becomes obsessed with one of his ancestors, is “a parable on the perils of research.” My advice is to spare yourself the trouble of trying to divine what’s true and what’s fiction in “The Night Ocean” and just go along for the ride.

Michaud is a novelist and the head librarian at the Center for Fiction.