Paul O’Connor: We pay but have no say in charter schools

Published 11:58 am Thursday, June 22, 2017

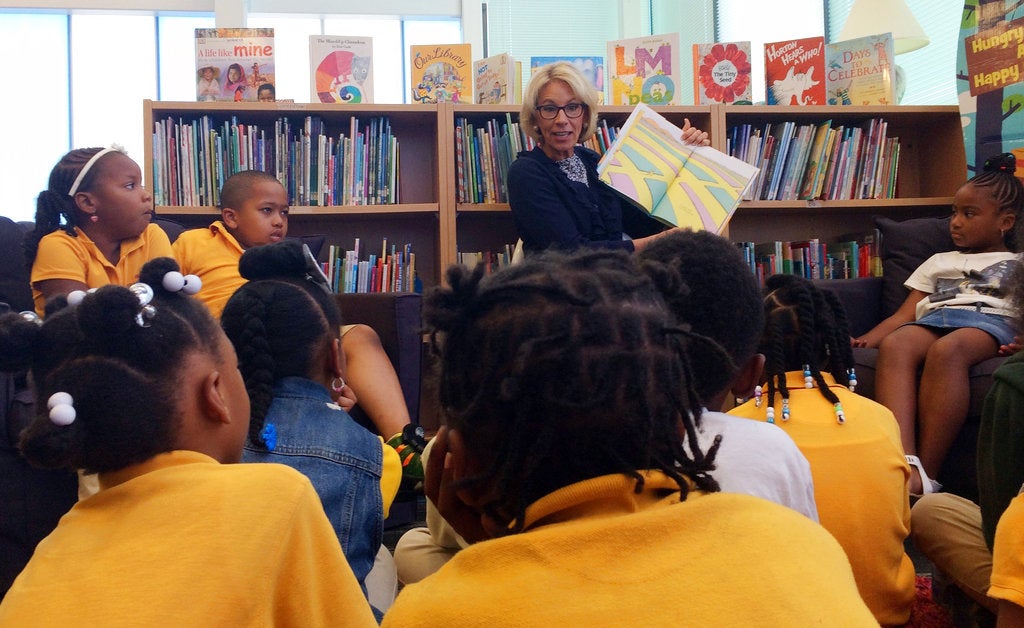

- Education Secretary Betsy DeVos reads to students at Eagle Academy Public Charter School in Washington, Friday, June 2, 2017. (AP Photo/Maria Danilova)

RALEIGH — Decades from now, the most enduring and defining mark of this Republican legislature may well be charter schools.

In 2011, Republicans came to power intent on lifting the 100-school cap that had existed since the mid-1990s. This school year, 168 charters operated in the state, educating more than 80,000 students, just over 5 percent of the state’s school population.

In a remarkable indicator of charter growth, the Wake County school system announced recently that it expects charters to gain more students next year, 2,535, than conventional public schools, 2,208, according to the News & Observer. If those numbers hold, Wake will have 13,349 students in charters, a total that exceeds the total conventional school populations of many county systems.

Public school advocates and the political left spend a lot of time lamenting this growth, but one concept seems to have escaped these critics. Charter schools are public schools, just a different kind. If the education of the populace is the goal, and these schools do that well, then there is nothing to lament.

If done correctly, charter schools can serve critical needs for the general population, filling gaps with specialized programs that the much larger, and usually uniform, conventional schools cannot.

But they must be done correctly, and that is a concern.

Charter schools originated in liberal Minnesota in the 1980s, but conservatives quickly put the idea on their agendas. Many saw charters as a way to re-segregate schools and to teach conservative values that they saw being overlooked.

The charter law in North Carolina was designed to avoid either of those eventualities, but critics say that the state hasn’t guarded against re-segregation, especially during the four years of the McCrory administration.

The argument points out the fundamental flaw of charter schools as operated in North Carolina: Taxpayers have almost no say in how they operate.

With conventional schools, we each have a vote for the school board members who run that system. If they are setting unpopular policies, we can rally opposition and vote school board members out of office. With charters, we can only complain to a statewide board of political appointees and the governor. We’re unlikely to get much attention when we complain that eighth-graders should not be reading this book or that.

Charter school advocates respond that parents have a lot of say in how charters are run, and that is most important. Yes, it is important, but those parents aren’t shouldering the entire cost of running those charters. Charters run with tax dollars from all of us, and they are producing the generation of North Carolinians who will follow us. We should all have a say in how those schools operate, even if our kids don’t attend.

Let’s take the example hinted at above. A charter in our county selects an eighth-grade reading list consisting of material distasteful to many of us. The books teach salacious behavior or anti-American political values. We can pressure conventional public schools to review that list, but we have little input in the charters because our children don’t attend them, only our dollars do.

The same problem exists, only more so, with vouchers for private schools, and the legislature is determined to increase spending there, too.

In the effort to provide more options for parents, North Carolina, it appears, is also taking the democratic element out of public education.

Paul T. O’Connor has covered state government for 39 years.