Paul O’Connor: As cities grow, rural areas will lose clout in legislature

Published 12:00 am Thursday, July 13, 2017

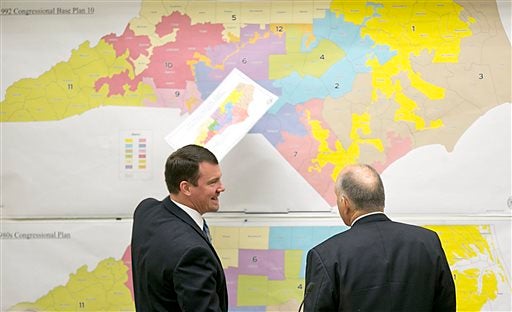

- State Sens. Dan Soucek, left, and Brent Jackson review historical maps during a Senate Redistricting Committee meeting in 2016, in Raleigh. (Corey Lowenstein/The News & Observer via AP)

RALEIGH — Ferrel Guillory, the former newsman and current UNC scholar, often lectures to journalists with slides that reporters have nicknamed “Dots, Dots, Dots.”

Guillory starts with a fairly blank 19th century map of North Carolina. Using U.S. Census data, he notes population centers with black dots, creating a new map for every new data set, that is, every tenth year.

The first slide has a few dots and mostly white space, the representation one would expect of an agrarian state with a scattered population. More recent slides show large, dense black splotches representative of a rapidly urbanizing state with stagnating rural areas.

The population shift that Guillory depicts has ramifications for all aspects of life here — jobs, education, culture, the environment and, importantly in the next three years, state politics.

The 2011 Republican redistricting maps gave the GOP large advantage in both the U.S. Congress and the state legislature by carving serpentine districts that combined rural areas with Republican suburban voters. It then packed Democrats, especially black Democrats, into a small number of districts where they won by huge margins. In effect, they diluted the urban Democratic vote.

Later this summer, the legislature, under court order, must redraw many of those districts. The calculations for a strong Republican majority will be more difficult because legislators won’t be allowed to pack black Democrats to give Republicans an advantage.

Another factor comes into play. When redrawing districts in court cases such as this, legislators must use the data collected in the last census. That was in 2010, and the data is now more than seven years . There is considerable evidence that in that interim many people have moved.

Just last week, the UNC Population Center reported that 41 percent of the state’s municipalities, those in rural counties, experienced populations decline between 2010 and 2016 while the major urban centers grew rapidly.

That means fewer seats for the rural, and more for the urban, areas due to the one person, one vote, mandate.

National Republican mapmakers, who are most likely using powerful computerized programs to draw the maps right now, will have to compose districts using 2010 census data to satisfy the courts. But, to maintain a big majority, they must consider the recent population shifts to base their districts on the people who are still living and voting in them. That will not be so easy.

Long term, the population shift has more serious ramifications for political maps. The shift that we’ve seen since the end of World War II will continue to reduce the rural voting strength of the conservative party. Republicans will become ever more dependent on urban-county voters, and, for sure, plenty of them are conservatives. But it gets harder to carve precise maps in the suburbs because the population is more heterogeneous and transient. Just because a Democrat lives in the house at 11 Maple St. today doesn’t mean a Republican won’t live there next, after that Democrat gets transferred to Denver.

Things will get much more interesting if the U.S. Supreme Court, next year, outlaws or handcuffs political gerrymandering, as it will have the opportunity to do. The court could order that maps represent “communities of interest.” Any such mandate ties the hands of those doing the gerrymandering.

Many Democrats expect demographic and residential shifts to rescue their party in the 2021 redistricting. That’s far from certain. But one thing is as clear as a black dot: North Carolina’s rural areas will continue to lose political clout, maybe not significantly this year but certainly in bigger terms in 2021.

Paul T. O’Connor has covered state government for 39 years.