Can love survive all the leaving?

Published 12:00 am Sunday, July 23, 2017

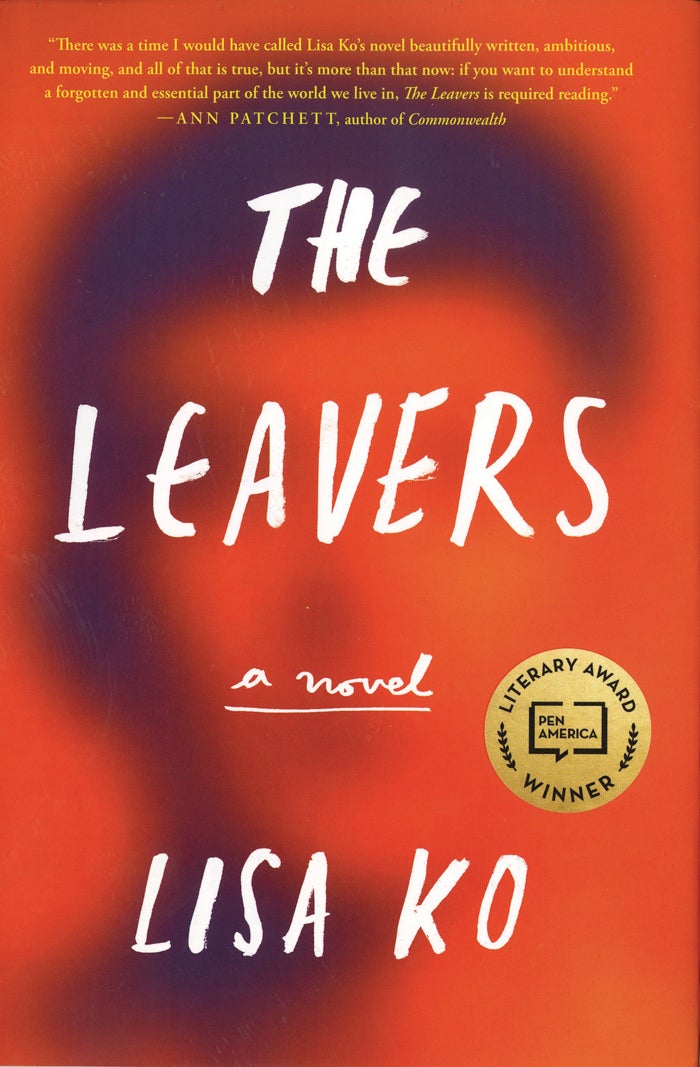

“The Leavers” by Lisa Ko. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. $2017. 335 pp.

By Deirdre Parker Smith

deirdre.smith@salisburypost.com

Inspired, or more likely, enraged by immigrants deported and forced to leave their American children behind, accounts of privately run deportation jails and the assumption that the children are better off with white American parents, Lisa Ko wrote her first novel, “The Leavers.”

It’s story of a mother and son torn apart, of the mother and son constantly reinventing themselves to find out who they are, and it exposes what can happen to immigrants and their children.

It is fiction, but Ko began saving articles in the 2000s and decided to write her book in 2009, before deportation became a hot topic.

She based this novel on the real story of Xiu Ping Jiang, an undocumented immigrant from Fuzhou, China, the setting of part of the book.

Jiang was stopped while riding on a bus from New York City to Florida. She was held for more than a year in a deportation jail, often in solitary confinement. She had tried to bring her 8-year-old son into the U.S. from Canada but he was caught and later adopted by a Canadian family.

Ko’s story is about Peilan Guo, from Fuzhou, an industrial city, and her son, Deming, born in America after Peilan, now Polly, escapes China in a box and lands in New York City.

Polly works a low-paying job in a garment factory, lives in a tiny apartment with eight other women, stacked on bunks three high. Deming’s birth provides complications, so Polly sends him to China to be raised by her father until he is old enough to go to school.

Polly is ambitious, restless, but exhausted. She likes to lose herself in the huge city, walking, walking, riding a train or bus to the end of the line, getting lost.

With a small child, she becomes claustrophobic. It’s harder to escape.

With Deming in China, she finds friends, a lover, and leaves the factory for a nail salon. When he comes back, they share an apartment with Leon, Polly’s lover, his sister, Vivian, and her son, Michael. The four form a family until the day Polly doesn’t come home.

No one knows where she is, and after as much searching as they dare, they assume she has left for Florida for a job.

Deming is devastated; as time passes, Vivian feels she has no choice but to relinquish Deming for adoption.

He then becomes Daniel. Daniel Wilkinson, child of American parents, professors at a small college upstate. He loses the only people he has ever known, his only friends, his moorings, his background, heritage, everything.

The rest of the book is about Daniel/Deming’s struggles to find a place in this world, to know who he is. What he will be is a total mystery, especially to him.

It’s heart-breaking to see him searching, lost, with new parents Kay and Peter unsure or unable to give him what he needs.

Daniel is as restless as his mother. His boundaries, the expectations of his parents are too limiting.

He turns to gambling for the thrill, for the risk. Losing is a way to punish himself for whatever he did wrong to lose his birth mother.

How can he trust Kay and Peter? He thought he could trust Leon, Vivian and Michael, but they gave him away. How can Daniel trust anyone? He’s an outsider, a foreigner in his own country.

Daniel has no idea who he is, having spent the first six years of his life in a Chinese village with his grandfather, the next five in New York City, where his mother takes low-paying, claustrophobic jobs because that’s all their is, then years with his adoptive parents in a town that has nothing to offer him. He’s not going to be the person Kay and Peter want him to be.

Always, he is plagued by the question of his mother’s disappearance. Did she abandon him? What happened to her? When he begins to search, how can he accept the results?

Polly wants what she wants and her son will have to adapt. Daniel is selfish because he realizes he can please no one.

Some reviewers found Polly’s flaws too great, but they make the book more believable. She’s not the heroine, she’s a victim of circumstance and ambition. Should we expect her to be the perfect mother?

Deming, too, is flawed, as he would be, given the life he’s lived so far. No one here is perfect. That’s the strength of the story. There are no saviors. There are trials, mistakes, errors, suffering, uncertainty.

When Ko introduces the chapters that Polly narrates, the readers get a more detailed picture of what she has suffered while her son is suffering.

It is not until late in the book that she is able to tell what happened to her, and those details of an immigrant roundup, detainment in a deportation camp and the awful treatment there earned Ko the PEN/Bellwether prize established by Barbara Kingsolver to promote fiction that addresses issues of social justice.

Who are the leavers of the title? All of them, from Polly to Daniel, and all the people Daniel knows. His mother leaves him, his beloved Leon leaves him, his adopted parents abandon him when he does not live up to their expectations. His best friend kicks him out of a band.

Later, Daniel leaves, too. It seems life is about leaving.

Ko’s insights into the mother and son who are so alike make the story ring true. What she has to say is revealing and humbling to the reader. And it raises the question about what value we put on life.