A found 1856 medical diary prompts a leap into history

Published 12:00 am Tuesday, August 15, 2017

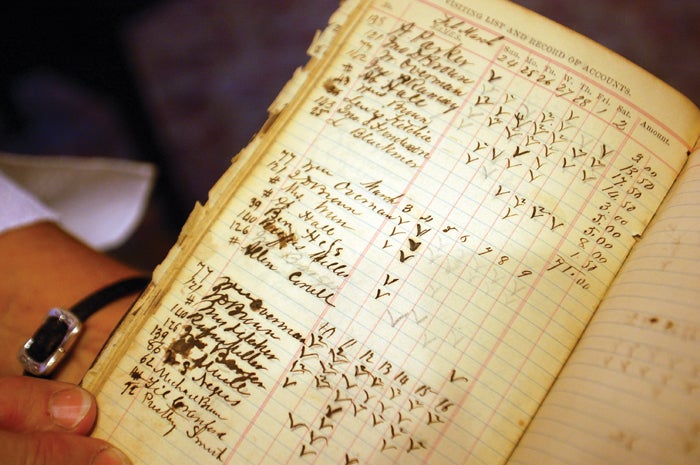

- This is a 'visiting list and record of accounts' page from Dr. J.J. Summerell's daily pocket record. It reflects days from February and March 1856. Mark Wineka/Salisbury Post

SALISBURY — Melissa Eller recently was going through boxes left behind by her late father, Vance Eller, when she spied a worn, leather-bound book, the size of which could fit into the breast pocket of a man’s coat.

“I don’t know how I overlooked it before,” Eller said.

The name of Dr. J.J. Summerell was embossed on the front, which also indicated this was a “Physician’s Daily Pocket Record.”

As Eller delicately turned the pages, she realized she was reading mostly an account of the patients Summerell had visited or treated and, in some cases, how much he had charged them during the months of 1856.

This local medical diary, Eller realized, was 160 years old.

Summerell also had made random notations of remedies and formulas he prescribed.

The patient names in the record book are familiar to Salisburians and include the likes of Blackmer, Overman, Ketchie, Brown, Ramsay, Hall and Parker.

Eller says she’s not sure what she will do with the book. It definitely represents the kind of history her father was interested in and would have purchased at, say, an estate sale or auction.

Vance Eller wore many hats during his life. He was a longtime pharmaceutical salesman. He taught radiology for a time at Rowan Memorial Hospital. In addition, he was an owner of Eller-Wood Florists and helped establish the Southern Retail Florists Association.

Eller also was fascinated with history and archaeology and did some of the digging at Town Creek Indian Mound with his friend Dr. Peter Cooper. So it wasn’t surprising that Eller had Summerell’s old medical diary in his possession.

For now, Melissa Eller has made sure that Rowan Public Library has a digital copy of the book.

She also recently shared it with J.J. Summerell of Greensboro, whose namesake and great-great-grandfather was the same Dr. Summerell.

Susan Sides, president of the Historic Salisbury Foundation, arranged the meeting in a Salisbury Station conference room.

“I thought J.J. would love to see this,” she said.

Summerell, who is in the insurance business in Greensboro, lived in Salisbury until his senior year of high school. He happens to own an amputation kit that belonged to Dr. Summerell, and he brought it with him to show Eller and Sides.

Meanwhile, Sides had delved a bit into the background of Dr. John Joseph Summerell and found some interesting connections to the Civil War, Mount Mitchell, local medicine and a famous Salisbury book.

•••

Summerell was the son-in-law of Dr. Elisha Mitchell, a noted geologist and botanist and for whom Mount Mitchell is named. Summerell was married to Mitchell’s second daughter, Ellen.

At Ellen’s death in late 1887, The Salisbury Truth newspaper said Mitchell was “so long a distinguished Professor in the University of North Carolina, and generally recognized in his day as the most learned man in the State, who perished a martyr to science in the gorges of the Black Mountain in 1857, and whose remains now repose on the highest peak of that range, nearly seven thousand feet above the level of the sea.”

A native of Chapel Hill, Ellen Mitchell married Dr. J.J. Summerell in 1844, and the couple immediately moved to Salisbury, where they would live out their lives. The Truth’s obituary said Ellen Summerell was “wife of one of the leading physicians of the town, for the long period of forty-three years.”

“In those early days,” the obituary continued, “she was accustomed to relieve her husband, wearied by the labors of an exhausting occupation, by reading to him hour after hour the medical books and journals of the profession.

“She thus acquired for herself a valuable knowledge of medical science and of the name, proportions, and properties of the remedies employed in the healing art.”

Dr. J.J. and Ellen Summerell had seven children and attended First Presbyterian Church. One of their children was author G. Hope Summerell Chamberlain, best remembered in Salisbury history for the book “This Was Home,” her reminiscences of growing up in Salisbury.

Chamberlain was born June 21, 1870, and died May 23, 1960, in Chapel Hill.

•••

Sides also found mention of Dr. Summerell in a story from the Carolina Watchman on April 13, 1882, in which the editor was recalling the 17th anniversary of Stoneman’s Raid in Salisbury at the end of the Civil War.

“April 12 — This day, 17 years ago, the Rev. J. Rumple was a prisoner in the prison,” the Watchman said. “Dr. J.J. Summerell was also a prisoner, but on the way to prison slipped out, some how, and afterwards had the face to apply for and secure the release of his pastor.”

According to the Watchman’s story, “a long list of our best citizens” apparently were rounded up and jailed while Union Gen. George Stoneman was in town.

In a newspaper advertisement in December 1865 after the Civil War was over, Summerell joined other doctors of the day — Marcellus Whitehead, I.W. Jones, C.A. Henderson, Stiles Kennedy, J.A. Caldwell, W.H. Cole and Oliver Hicks — in publishing what their fees for services would be.

The fees were decided at a meeting of the doctors on Dec. 6, 1865. Among the charges noted were $2 for a visit in town during the day; $5 per nighttime visit; $10 for a consultation fee, plus visit; $3 for a visit in the country that was 3 miles or less; and anything over 3 miles was $1 per mile, and double rates at night.

An office prescription was $2.

It was obvious Summerell and his doctor friends were having trouble being paid after the war. The doctors “resolved” in the advertisement that “every branch of business is now conducted exclusively on the cash system.”

“It becomes necessary for us to require of our patrons prompt cash payment of our bills,” the doctors added.

•••

Sides located an 1887 letter Summerell wrote to the North Carolina Herald newspaper, which also was published in Salisbury. In the letter, he was speaking of the necessity to keep a better record of deaths in Salisbury and Rowan County.

“There is no law in Salisbury for keeping a record of deaths, except so far as it is the duty of the treasurer of the city to keep a list of the permits of burial of white people in public graveyards,” Summerell said.

“And even this is not an accurate or reliable way (of) keeping such records.” He cited examples of how the “book of the treasurer cannot be a correct record of the monthly mortality.”

At the time, Summerell carried the extra title of Rowan County superintendent of health, a position he held for more than 30 years. He also was the longtime physician for the County Home of the Aged and Infirm.

In 1862, during the Civil War, Summerell was elected president of the State Medical Society. He also was one of the physicians serving the Wayside Hospital during the Civil War.

One of Dr. J.J. and Ellen Summerell’s other children, Elisha Mitchell Summerell (1858-1934), also became a physician. For about six years, Elisha served as superintendent of the asylum in Morganton before he returned to Rowan County in 1890, settled in Mill Bridge and practiced medicine until his death.

Dr. J.J. Summerell died Dec. 17, 1893, at the age of 74. The Carolina Watchman wrote a lengthy obituary on Summerell under a subhead that said, “A Short Sketch of the Life and Career of a Good Man and Useful Citizen.”

“His venerable form, so long familiar to our streets, will be sadly missed,” the obituary said.

Summerell was an 1842 graduate of the University of North Carolina and 1844 graduate of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. That same year, he started practicing medicine in Salisbury.

“During this whole period of nearly 50 years,” the Watchman said, “Dr. Summerell has confined himself strictly to his profession, in which he was eminently successful, enjoying the confidence of the community and the respect and honor of his medical brethren throughout the State.”

Find a little book, Melissa Eller will tell you, and it opens the window to history.

Contact Mark Wineka at 704-797-4263 or mark.wineka@salisburypost.com.