James A Wicks: Confederate submarine H.L. Hunley crew member from Salisbury?

Published 12:05 am Monday, October 23, 2017

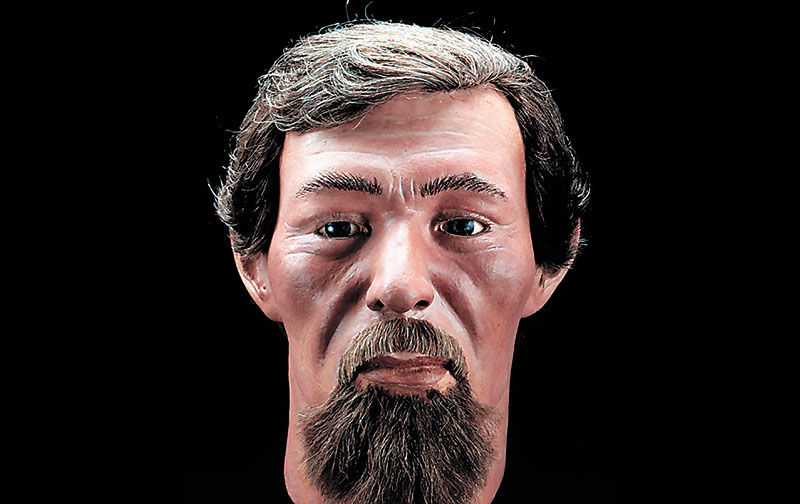

- James A. Wicks, H.L. Hunley crew member. photo from Friends of the Hunley website

By Wayne Hinshaw

For the Salisbury Post

In writing a column about the cause of death of the Confederate submarine crew members on the CSS Hunley in Charleston Harbor, S.C., it was pointed out to me that it is possible than crewman James A. Wicks was from Salisbury. I was told there was a newspaper article published on Sept. 27, 1922, in the Salisbury Evening Post stating that James Weeks (Wicks) was from Salisbury. I attribute the spelling of the name Weeks, instead of the correct spelling Wicks, to a reporter’s error or misunderstanding of the interviewee.

As with most historical research, when you open one door, you are then faced with five hallways. Recorded facts and dates on a subject are not always the same and sometimes disagree. You can gather information and it falls where it falls and sometimes it is not in a straight line as you hoped.

The Post interview was with Salisbury native and resident Thomas P. Johnston, who was the only remaining living member of the N.C. Confederate Navy. Johnston was born in Salisbury in 1845 and attended local schools. He was a Sunday school teacher at First Presbyterian Church and in later years, he ran for North Carolina governor on the Prohibition ticket and lost.

Wearing his Confederate officer uniform for the interview and photo, Johnston recalled that five men from Salisbury, including himself, entered the Confederate Navy together in 1864.

The Post article stated:

“It was in this activity off the Charleston harbor that Jim Weeks (Wicks), one the youthful naval fighters from Salisbury, lost his life in a most heroic manner. The first submarine was built and it was sent out to attack and sink vessels of the enemy. This cigar-shaped boat carried a volunteer crew when she submerged and sunk the Housatonie, but herself met with disaster and all the crew perished. On the battery at Charleston is a monument to the Salisbury lad, Jim Weeks (Wicks), who gave his life in this daring undertaking which proved successful.”

We have more information about James A. Wicks than any of the other Hunley crew members because he had joined and served in the U.S. (Union) Navy 10 years before the Civil War. His Union military records show that he joined in 1850 and served as a seaman and later as a quartermaster. His records only say that he was from North Carolina, listing no hometown. He joined the U.S. Navy in New York and was stationed in Brooklyn, N.Y., and was married and had four daughters.

Wicks’ wife, Catherine Kelly, was born in England in 1836. His daughters were Mary (born in N.Y.), Josephine (born in N.C.), Lori (born in N.C.), and Laura (born in Fla.).

After Wicks’ death, Catherine remarried to Henry Peterson and they had a daughter named Maggie Peterson (born in Fla.) in 1865. This information came from the 1870 census for the city of Fernandina in Nassau County, Fla., when the family moved at the start of the Civil War.

Interestingly, James A. Wicks, doesn’t show up in any of the North Carolina or Florida census records. The Confederate Navy records either do not exist or are lost.

Wicks served on the USS Navy ships Braziliera and Congress. He was serving on the USS Congress in March 1862 and witnessed the Battle of Hampton Roads off the coast of Newport News, Va., where the CSS Virginia (formerly the Merimac) battled the USS Monitor. The CSS Virginia sank the USS Cumberland and crippled Wicks’ ship, the USS Congress. At this time, Wicks was about 40 years old when the USS Congress sank.

There is only speculation on why Wicks left the Union Navy and joined the Confederate Navy, but maybe it was because his native state of North Carolina had joined the Confederacy, or because his wife and family were living in Florida.

At this point, Wicks left the Union Navy, went to Richmond, Va., and enlisted in the Confederate Navy on April 7, 1862, as a seaman. He was assigned to the CSS Indian Chief where he was promoted to boatswain’s mate. It was while serving on the CSS Indian Chief that Lt. George E. Dixon, commander of the H.L. Hunley (submarine), gathered five of his volunteers from the Indian Chief for his H.L. Hunley crew.

Wicks took a leave from the Hunley mission and participated in a Confederate Navy night raid in New Bern, N.C., on the USS Underwriter ship. He reported back to Charleston on Feb. 5, 1864, for the historic submarine mission.

In the H.L. Hunley, Wicks was assigned the No. 6 crank position in the hand-cranked submarine. There was also an emergency release lever at his position, but it was never released when it sank. Archaeologist Maria Jacobsen said, “During the excavation (of the sunken submarine), we found a keel release mechanism below the station manned by Wicks.”

Wicks’ remains were found with seven U.S. Navy buttons, possibly from his service with the Union Navy. Maybe he was wearing a Union Navy jacket on this mission. Wicks’ remains were also found with a silk bandanna around his neck. It was one of the few pieces of cloth textiles that had survived the years in the sea. The cloth of the bandanna had been bleached out and it had become mineralized and hardened and the knot could not be untied.

Linda Abrams, forensic genealogist on the Hunley project, said, “Wicks’ surviving relatives and his service in the U.S. Navy have enabled me to learn much about the appearance of this man. According to records, he had light brown hair, blue eyes and a florid complexion.” He was 5 feet, 10 inches tall and a heavy tobacco user. He was the only crew member known to be married and have children. He is believed to be the oldest crew member on the Hunley.

On August 27, 1909, the Concord Daily Tribune in Concord ran an article about Wicks’ daughter. The article reads,”Mrs. Harry Barker, of Jacksonville, Fla., who has been in the city for several days looking into the war record of her father, James A. Wicks, left this morning for Salisbury, at which place her father enlisted in the Confederacy. Mrs. Barker was six years old when her father moved from this city (Concord) to Fernandina, Fla, in 1859, shortly after which Mr. Wicks joined the Army; being a sailor was transferred at Richmond to the Navy and placed on the sub-marine boat that was blown up and sank in the Charleston harbor. He was one of seven killed or drowned in the sinking of the vessel and today there is a monument on the battery at Charleston to the memory of her father. Mrs. Barker is highly pleased with Concord and the reception accorded her by the friends of her deceased father and her grand mother, Mrs. Lovey Wicks, both of whom are well remembered by a numbers of older residents.”

In 2010, a memorial marker was placed in the Oakwood Cemetery in Raleigh in honor of the CSS H.L. Hunley submarine. The inscription reads in part, “On February 17, 1864 the CSS H.L. Hunley was the first submarine to sink an enemy ship in combat. … Perishing crew member James A. Wicks was from North Carolina. Whereas it played a major roll in American naval history. …”

Information for this article came from The Friends of the Hunley, the Hunley Project, the S.C. Hunley Commission, Clemson University, Restoration Institute, Naval History and Heritage Command, the Charleston Naval Complex Redevelopment Authority, the Rowan Public Library History Room, the Salisbury Evening Post, the Concord Daily Tribune, Donna Poteat and Ray Barber.